Back in 2015, while traveling during the spring, I met A Chu at his family's homestay, which was still under construction. After a family dinner with many delicious dishes cooked by A Chu's wife and granddaughter, gathered around the makeshift fireplace, accompanied by the melodious and captivating H'Mong flute music that A Chu played, we exchanged many experiences to help each other continue our journey of spreading our culture to tourists who might have the chance to stay at his family's home.

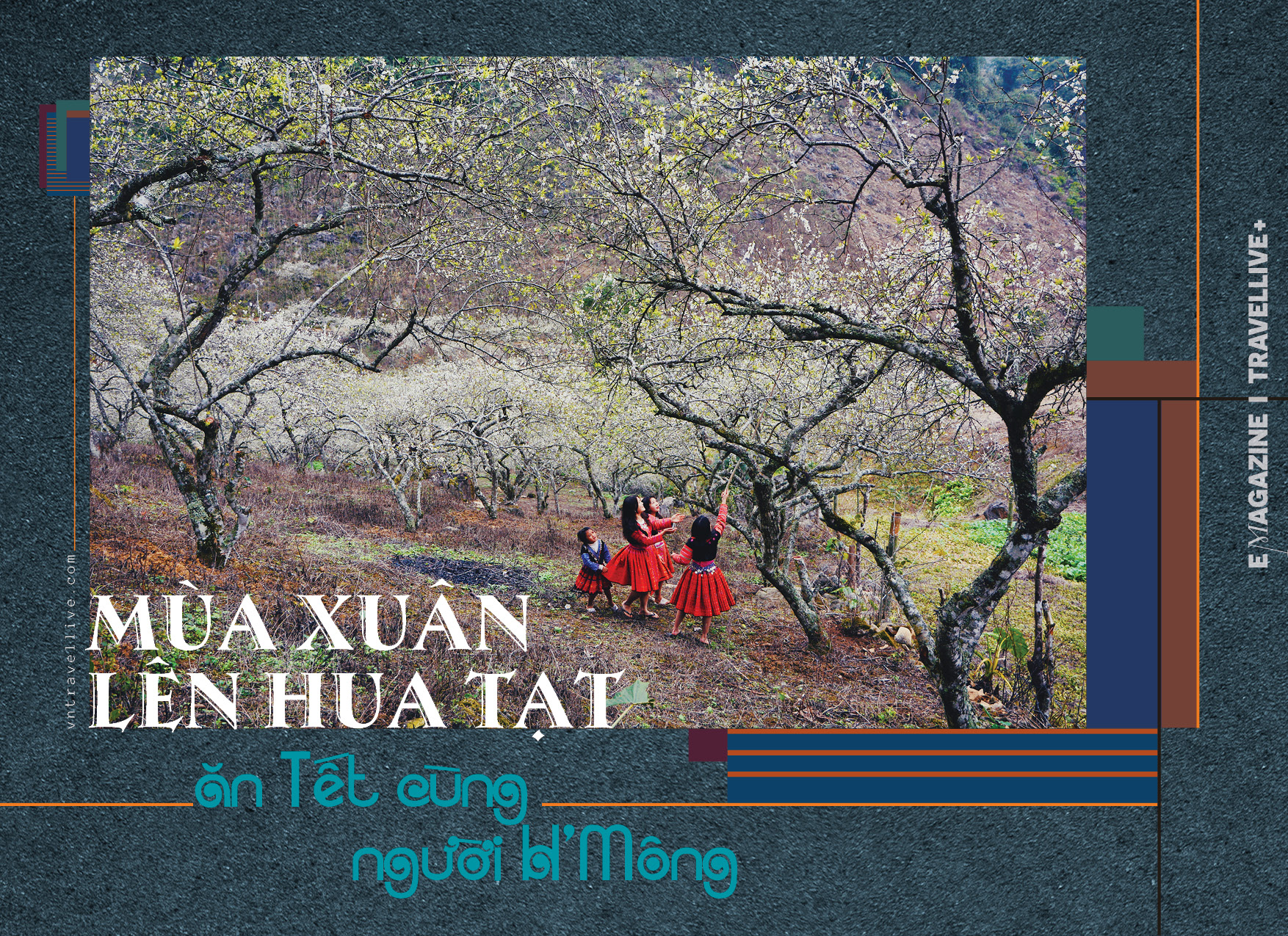

Hua Tat village nestles in a valley right in the middle of Hua Tat pass on National Highway 6 leading to Moc Chau city in Son La province, with very picturesque scenery.

Back then, Trang A Chu was one of the first people in his village to attend university. After graduating, he returned to his village and became the "Chairman of the Single Men's Association" because all his contemporaries had already gotten married. Not far away, Sua, A Chu's future wife, also became the "Chairman of the Single Women's Association" through her education. It was through education that the two met and voluntarily married. But it was only when they ventured into tourism that the literacy they had learned truly came into play.

Thanks to his sharp intellect and strong learning spirit, A Chu quickly recognized the potential of Hua Tat village – where the majority of his H'Mong people live. He became a leader in promoting the culture and identity of his people to tourists through his family's homestay.

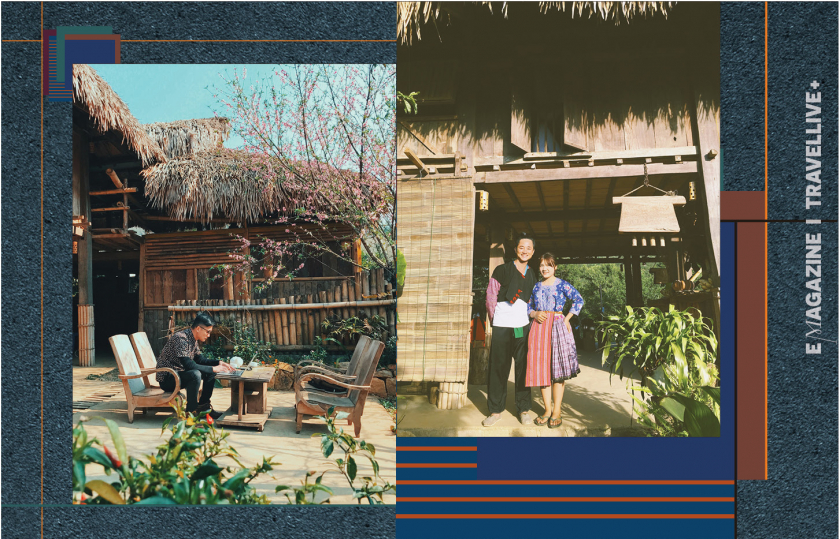

A Chu's homestay isn't a traditional H'Mong house – which is built low to avoid strong winds. A Chu went to Mai Chau to observe the Thai people's tourism practices and learned from them – a spacious, airy stilt house, suitable for tourists, especially foreigners. Returning to his village, A Chu started building a more versatile and unique homestay. It includes stilt houses for group accommodation and bungalows/villas for guests who want privacy during their stay.

A Chu personally arranged stones (like the Hmong people often arrange stones to build fences) to create... a reception counter, a bar, or a fireplace. In the bathroom area, A Chu used bamboo cladding and Hmong fabrics woven by Sua as decorative curtains, creating eye-catching works of art with unique patterns that pique the curiosity of those using the restroom.

From buffalo bells and plowshares to corn mortars, crossbows, and knives, A Chu arranges and decorates his house to introduce the culture and customs of the H'Mông people to tourists. Anyone with a keen eye or a love for exploration can learn many new things during their stay at A Chu's house. Every time I visit, there's something new for me to ask my "guide," A Chu, to show me.

From the moment we first met, we grew fond of each other, and every year I visit Hua Tat village several times. Spring, summer, autumn, and winter, I've been there in every season. But A Chu always invites me to visit during the H'Mong New Year so I can see even more wonderful things. And so, I've celebrated two New Year's celebrations with my sworn H'Mong brother in Hua Tat village.

Like many Hmong people throughout the country, when peach blossoms burst into bloom and plum blossoms turn white across the fields and mountains, the Hmong people of Lenh village in Hua Tat celebrate Tet, starting from the 30th day of the 11th lunar month.

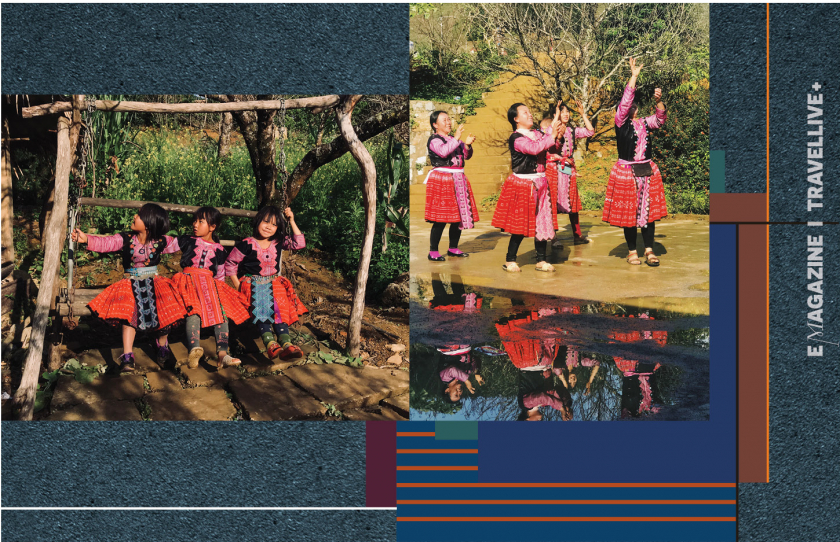

During this time, every household is bustling with activity. Children and grandchildren who work far away return home to reunite and celebrate Tet together. If one family celebrates Tet today, another will visit tomorrow, inviting each other over for about a month, until the Lunar New Year marks the end of the H'Mông New Year celebrations.

That day, I went with a few friends and found A Chu's house crowded with people – all relatives, neighbors, and friends. Many delicious dishes were being prepared by the women, such as boiled black chicken, fried eggs with mugwort, and mustard greens with boiled duck eggs and fish sauce; the boys and men were in charge of grilling chicken, roasting pork, or grilled offal... The aroma of the food filled the large garden, distracting even the H'Mông youths playing football in the neighboring stadium.

While serving the food, A Chu introduced me to the relatives at the party, and then we began raising our glasses of corn wine, brewed by A Chu's mother, to celebrate the New Year together. As we were feeling slightly tipsy, the music program began.

Besides his talent for playing the khene (a type of bamboo flute) like other Hmong boys his age, A Chu was also skilled at playing the flute and mouth organ, and combined his graceful xoe dances with his wife, Sua, making the performance stage in front of their house look like a spectacular variety show. The children, led by A Chu's sons Seo Linh and his little daughter My, also contributed many acts, making the evening even more lively.

By 10 p.m., everyone had gone home. The night in Hua Tat was cool and peaceful; you could hear the insects chirping, and every now and then, the sound of water dripping from the roof.

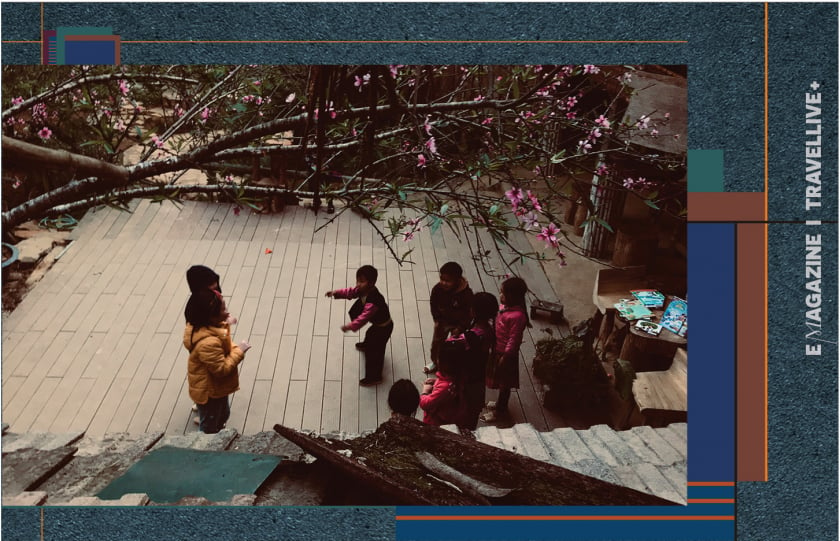

Waking up the next morning, looking out into the yard, I saw the sun shining, its rays sparkling through the dew drops still clinging to the peach blossoms, filling my heart with the spirit of "spring."

This morning, Seo Linh, A Chu's son, led my group to learn how to make traditional H'Mông paper. Seo Linh is in 7th grade this year, but he has been guiding people for over four years under his father's supervision, so he is very knowledgeable and quick-witted.

The paper-making house is also the house of the village's shaman - A Cua. Although called a shaman, A Cua is very young, a few years younger than me. But as A Chu briefly introduced, because the spirits "chose" A Cua to be a shaman when he was a teenager, despite his young appearance, A Cua's skills and experience are very "profound and extensive."

A Cua's professions as a shaman and paper-making are closely intertwined. Hmong paper is hung on the wall in the center of the house, often with a few rooster feathers attached, creating a sacred space and an altar for ancestor worship. Every year during Tet (Vietnamese New Year), the Hmong replace the paper with new pieces, hoping their ancestors will witness their sincerity and bless their descendants with a peaceful new year and a bountiful harvest. Small pieces of paper are also cut and pasted on corners, pillars, and household items, symbolizing sealing the end of the old year and welcoming the new one.

The group was given an explanation by A Cua about the process of selecting raw materials, and the traditional regulations and principles that papermakers must follow when making paper. And very honestly, A Cua confided that tourists experiencing this craft would contribute to preserving and conserving the H'Mông papermaking tradition, which is in danger of disappearing.

Once everything was ready, A Cua led the group out to the middle of the yard to try making it. The kids in the group were very excited to be free to create and decorate on the paper. The finished paper was left to dry in the sun, and it would be dry the next day.

That afternoon, Seo Linh continued to take the group on a walk around the village, passing plum and peach orchards, bamboo forests, jagged rocky outcrops, and even rows of white cabbage full of flowers, all very captivating to behold. As the sun began to set over the fields, the group returned to the homestay. The men had already set up the tools for making H'Mong sticky rice cakes right where the previous night's music stage had been. The glutinous rice, soaked in water for 6-8 hours beforehand, was steamed until cooked, then placed in a trough – a cleverly carved tree trunk – and pounded with pestles. Two people pounded rhythmically and evenly until the rice was smooth and sticky. Afterward, the women took the smoothed rice and sat in the courtyard, shaping it into large, palm-sized balls, wrapping them in banana leaves. When ready to eat, they flattened them and grilled or fried them, dipping them in honey – a unique and delicious version of sticky rice cake. The evening ended early, and A Chu told everyone to get some rest so they could wake up to watch the sunrise tomorrow.

At 4:30 a.m., we heard A Chu waking everyone up. Everyone quickly warmed up and got ready to set off to admire the beautiful scenery. After more than 30 minutes of travel, the whole group arrived at their destination, while it was still twilight.

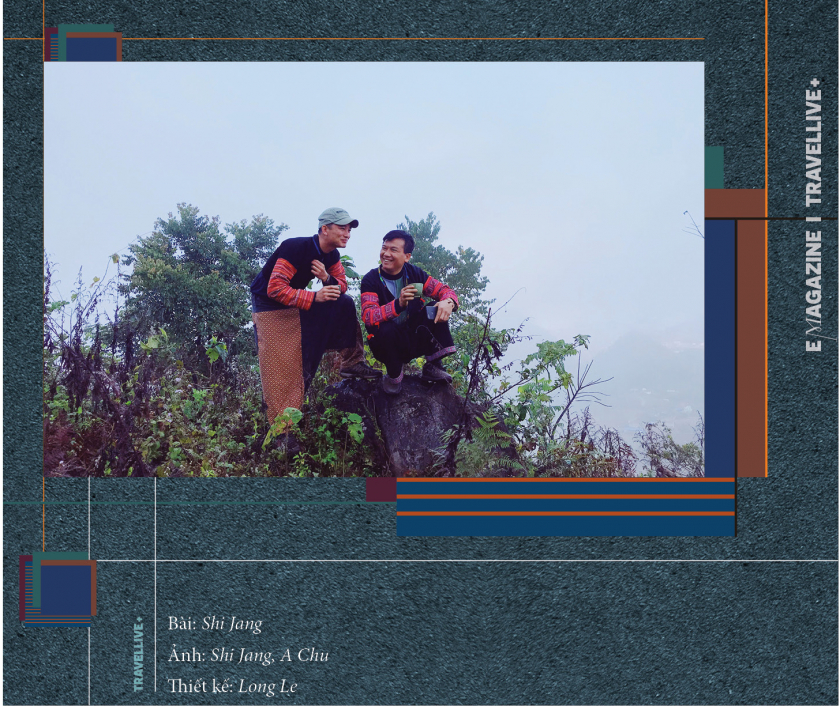

A Chu led the group, pointing out beautiful spots to watch the sunrise. The sound of roosters crowing still echoed from the houses of the villagers nearby. I laid out the tea and coffee I'd prepared earlier, along with the sticky rice cakes Sua had fried early in the morning, still warm. The scene was spectacular and beautiful as the sun rose from behind the mountain range. Right in front of us, fluffy white clouds floated over the valley. As the sun rose higher, its rays spread across the mountains, and the clouds dispersed, the whole group returned to the homestay.

Upon arriving, some continued drinking coffee, others sat in a corner by the veranda near the bar reading, some played with the Hmong dogs in the yard, and the children continued their joyful chatter under the peach and plum trees in the garden. A Chu also took the opportunity to chat about the family business, not forgetting to show me some new things he was working on – and I always see something new coming from him whenever I meet him, which I greatly admire.

A Cua appeared, carrying several sheets of Hmong paper that the group had used for their artwork the previous day, now completely dry. The children were delighted to see their finished creations and carefully wrapped them up under A Cua's guidance, after thanking A Cua in the Hmong language that Seo Linh had taught them during the walk the previous afternoon.

Sua had also finished preparing lunch for the group. After several days of bonding together, the final meal took place in a very intimate atmosphere, true to the principle that A Chu always instilled in her family when she started the homestay - which is to provide experiences that make guests stay a long time, enjoy themselves deeply, and remember them fondly.

Seo Linh clung to my arm while My shyly smiled and tugged at her mother's skirt as the group greeted each other. I squeezed A Chu's hand, wishing him good health so he could continue his career in community-based tourism, a project that God had so skillfully chosen for him.

And as you read about this journey, I'm probably about to welcome another early spring in Hua Tat village.

VI

VI EN

EN