When we mention Van Cao, we usually know him as the author of the Vietnamese national anthem, but such an introduction seems too brief compared to his contributions to poetry, music, and painting in the national art scene.

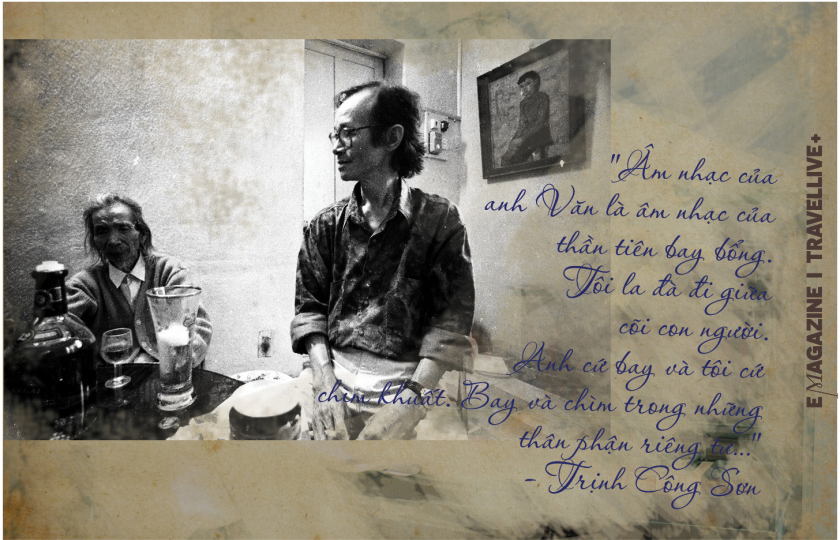

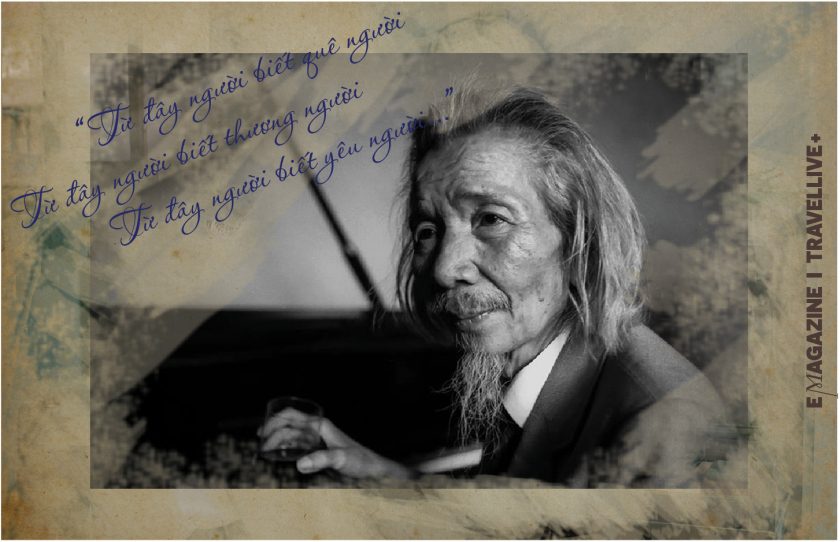

Trịnh Công Sơn once spoke of Văn Cao with such heartfelt words that music lovers have quoted and repeated them countless times in books, newspapers, and across social media: “In music, Văn Cao is as elegant as a king. In the field of songs, I am like a child dreaming of the sun as a kite to fly. Văn Cao’s music is the music of soaring fairies. I wander aimlessly among the human world. He keeps flying, and I keep sinking. Flying and sinking in our own private lives…”

It is not wrong to say that Van Cao was one of the most talented artists in Vietnam, with many contributions in the fields of music, poetry, and painting. In each field, he left behind numerous groundbreaking innovations for those who came after him, guiding and laying the foundation for the development of modern Vietnamese art and culture – especially his role in shaping the genres of love songs, heroic songs, and epic poems in music, as well as the epic poem genre in modern Vietnamese poetry.

In the pre-war era, Van Cao's love songs bore the strong imprint of Eastern poetry combined with Western classical elements, becoming timeless musical masterpieces such as:Sadness of Late Autumn,Spring Wharf,Ancient Melody,Lonely autumn,Dream Stream,Thien ThaigoodTruong Chi...In late 1944, Van Cao joined the Viet Minh with the first task of composing a marching song. The famine of 1945 and the revolutionary campaigns of that turbulent historical period inspired Van Cao to compose.Marching SongThe song has become the beloved national anthem of every Vietnamese person today. In the later period, Van Cao composed cheerful and energetic revolutionary songs such asMy village,Harvest season,Advance towards Hanoi…and especiallyEpic of the Lo RiverThe song has left a profound mark on the history of modern Vietnamese music. Pham Duy commented...Epic of the Lo RiverIt is considered "the pinnacle of resistance music in particular, and of Vietnamese modern music in general," and Van Cao is the "father" of Vietnamese heroic anthems and epic poems.

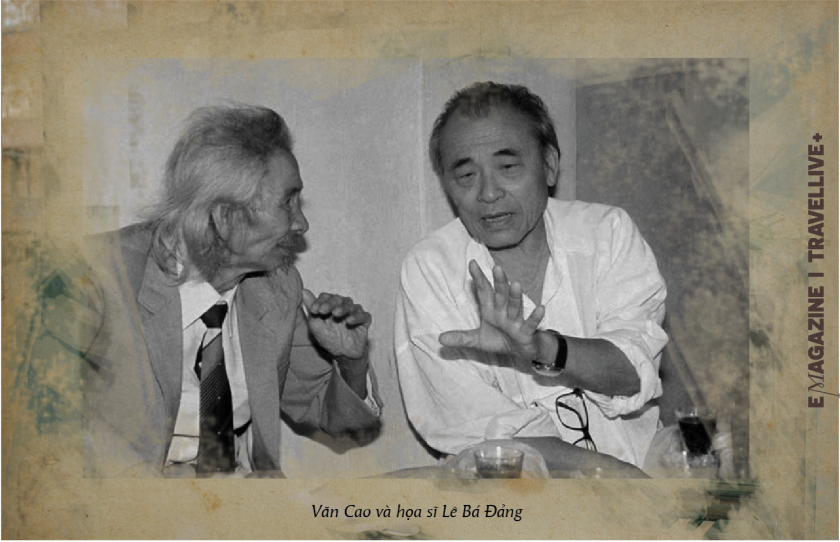

Not only a musical talent, Van Cao also wrote prose, poetry, and painted, achieving considerable success in each field. However, for various reasons, his contributions to poetry and painting are mentioned far less frequently than his achievements in music.

In the realm of poetry, Vietnamese readers are often familiar with his narrative verses about his own life, his homeland, and his free life with friends. Above all, they remember his poignant poems about the extreme poverty of the poor in the red-light districts, near train stations, on sidewalks, and in market corners. Van Cao believed that "a poet must seek out thoughts, emotions, and feelings in reality, in the people who are busy building things every day."

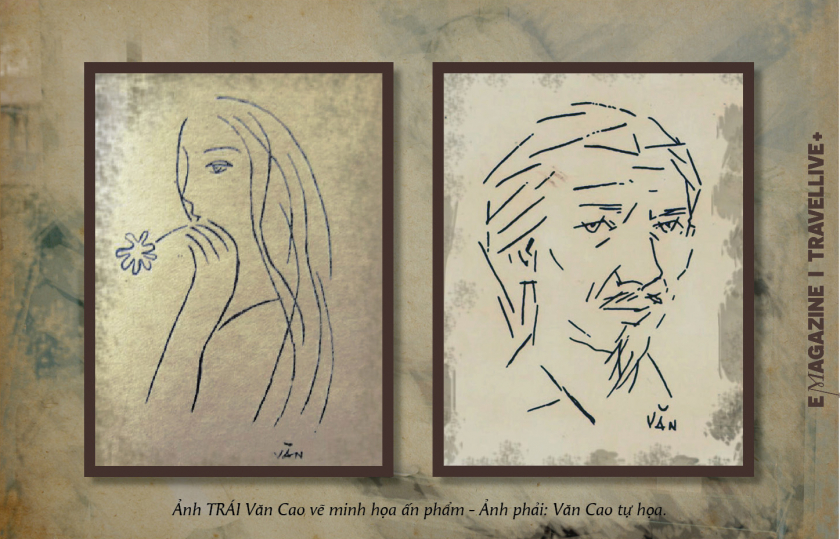

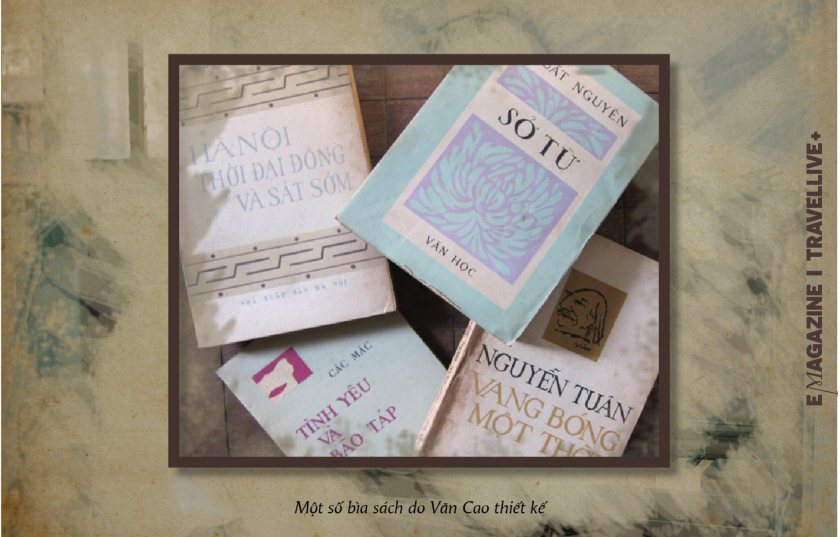

In the field of painting, Van Cao's works are not as complete as his musical and poetic works, due to various reasons such as the responsibility of those who preserve them and the limited preservation conditions during the war years. It is almost entirely possible to rely on the critical opinions of his contemporary artists, such as painter Ta Ty and art critic Thai Ba Van, who stated that Van Cao had "many valuable paintings with unique artistic value." How many is "many," and what constitutes "unique" is difficult for those seeking to understand Van Cao's painting style. However, the paintings included in the Vietnam Fine Arts Museum, along with other visual art works such as book cover illustrations, newspaper vignettes, and matchbox label designs, can reveal a part of his sharp and refined talent in painting, no less than his talent in poetry and music.

To think that Van Cao was a "wandering vagabond who forgot his homeland" is completely wrong. Having studied martial arts since the age of 9 and having fought in numerous matches in Hai Phong, the young Van Cao...Spring WharfHe's just as much of a gangster as Hứa Văn Cường.Shanghai Bund.In 1944, the artist put aside his pen and guitar and took up a gun, becoming the Captain of the Viet Minh Honor Guard – responsible for protecting propaganda members and dealing with traitors – essentially organizing assassinations in Hanoi under Japanese rule. He also spent time operating secretly in Lao Cai under the guise of being the flamboyant and stylish owner of a bar called Bien Thuy near Coc Lieu market. From there, Van Cao had the opportunity to meet, interact with, and become sworn brothers with the Hmong King.

However, Van Cao only took up arms because the social circumstances at the time forced him to; essentially, he remained an artist of the pen and the guitar. When his revolutionary mission was complete, Van Cao refused an offer to stay and work for the police force, saying, "This job is not suitable for me."

His son, the poet and painter Van Thao, recounted: "For Van Cao, eliminating someone was something he never wanted. But because of the revolutionary mission, because of the lives of countless people, he was forced to take action to eliminate these stubborn Vietnamese traitors."

Hoang Phu Ngoc Tuong once asked him: "Why, after the resistance war against the French, did you still paint and write poetry, but people no longer listened to you sing?" Van Cao replied: "When I accepted the offer to write..."Marching Song"I wasn't prepared to write a song; I was a dangerous commando. I was an armed commando. My mission was to go into a city one night, armed with a gun, and kill someone. I accomplished that. It was war and hatred, simple as that. In the early days after the war, I returned to that house and found only a widowed mother and her orphaned children. How could I express what was most important to me in the songs that followed? Should I talk about my heroic deeds or something else? So I remained silent and only wrote instrumental music."

After the 1954 Geneva Accords, Van Cao returned to Hanoi and worked for the radio station, but he wrote very little. In 1955, he resumed writing, contributing articles to the Giai Pham special issue. Along with several other artists, he advocated for freedom of art and creative expression. This was the reason that plunged him into darkness for many years. Van Cao was subjected to public denunciation and forced into labor camps. His name was almost never mentioned again, and his works were not performed in the North, except for the song...National Anthem- and he wasn't even credited as the author. For the next thirty years, he made a living doing various jobs such as writing music for films and plays, setting up stages, drawing advertisements for newspapers, designing matchstick labels...

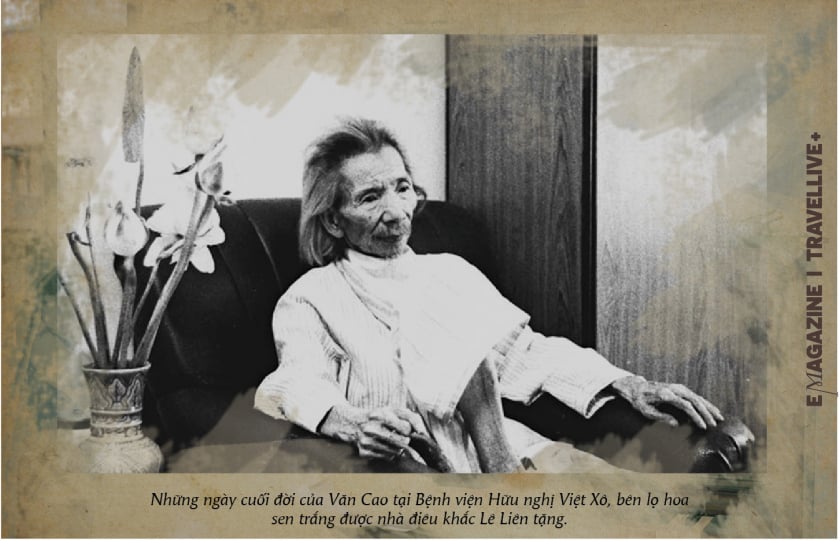

During this period, Van Cao hardly composed any more works, and his life with his family became extremely difficult. He endured the exile of his talent, like a "little prince" from a distant planet, loving Beauty and Poetry as he loved a fox cub and a rose, but something that "adults" could never understand. Unmentioned, uncomposed, and unrecognized, he lived like a prisoner on bail, silent and sorrowful.

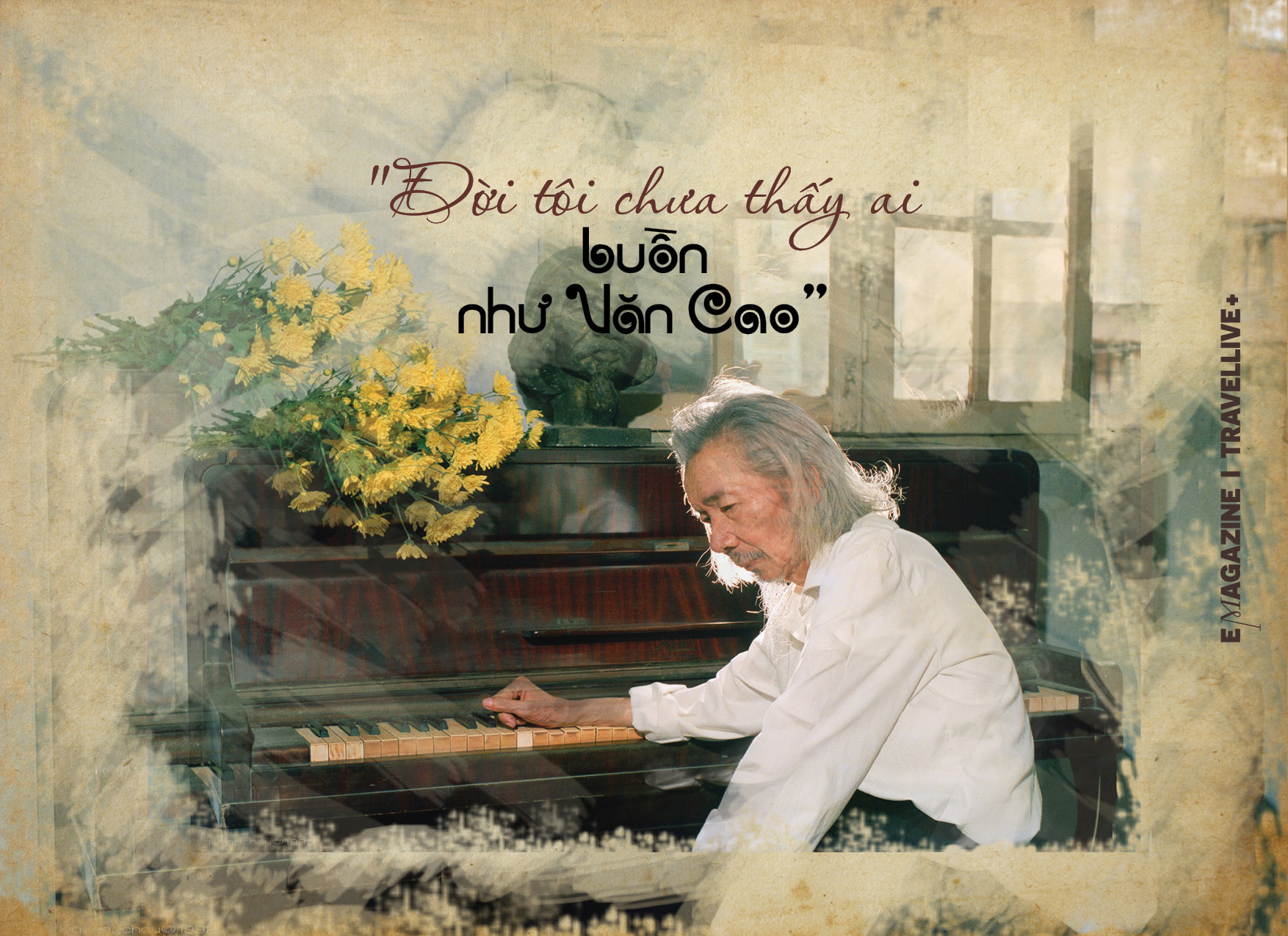

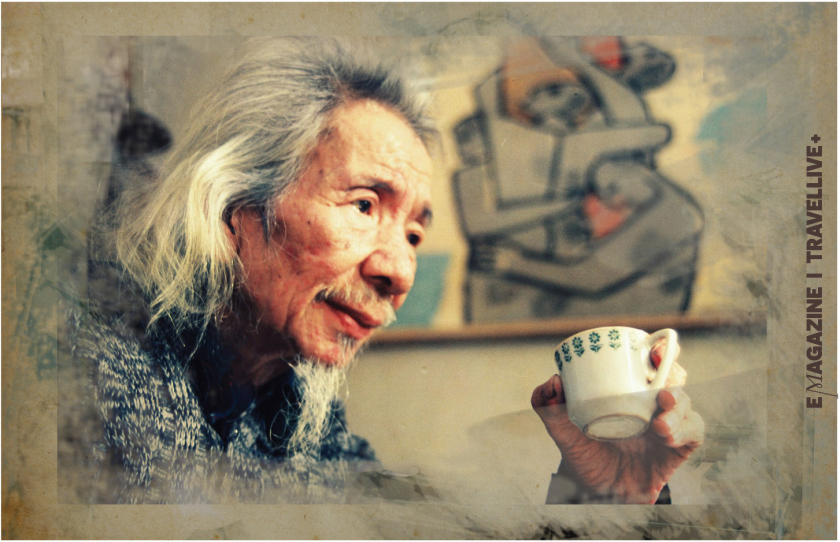

Photographer Nguyen Dinh Toan once said about Van Cao: "Many mornings, I would go to his house. He would just sit there with a glass of wine and a cigarette in his hand. Silent. I photographed him a lot, countless rolls of film. Pictures of him sitting by the piano, holding a glass or sometimes a cigarette. All his thoughts seemed to be frozen. We would just be silent like that. I almost never saw him smile. In my life, I've never seen anyone as sad as Van Cao, even though he never talked about it."

After 26 years without singing, in 1975, when the country was reunified, joy finally returned to the artist, prompting him to write the last work of his life. He wrote about "the ordinary season".

Van Cao named his last song...The first spring.Rejecting the fervent joy of peace and the familiar, lingering sadness, he instead painted a remarkably "ordinary" scene of the countryside, his elderly mother, and the sound of chickens clucking at midday... He returned tofirst springThese are primal, simple emotions, as if returning people to the purest, quietest, and most sacred joys deep within them – emotions that had been buried and lost for too long throughout the war.Paywe return to the lives of thosenormal season.

Sadly, at that time, "he" didn't yet know how to love, how to care for "him." The song was printed in the Saigon Liberation newspaper, but it soon became lost and forgotten amidst the heroic and proud melodies of the songs of the time. It wasn't until twenty years later, after the talented musician had passed away, that it was finally forgotten.first springIt has only recently begun to gain recognition.

After Vietnam implemented reforms, the bans on Van Cao's works were gradually lifted.

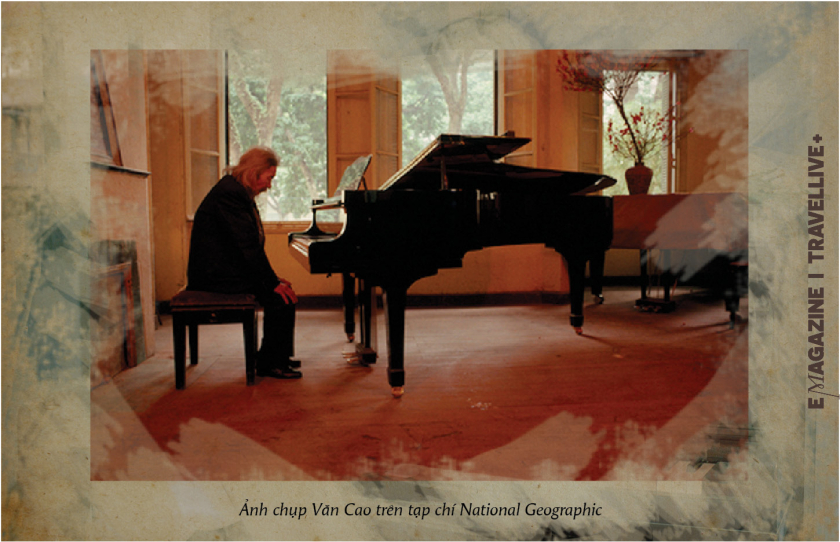

In 1989, a photograph of composer Văn Cao sitting thoughtfully beside a piano was published in National Geographic magazine. This very photograph inspired contemporary American composer Robert Ashley to compose a piano solo titled Văn Cao.Van Cao's Meditationin 1992.

The song itselffirst springIn 1976, shortly after it was composed, the song was somehow printed and performed all the way in the Soviet Union. The song even had Russian lyrics.

With countless works of art lost to oblivion, few today can truly understand the artist Van Cao. But the Vietnamese people, and even international friends, have not forgotten him. His spirit, his music, is still cherished and resonates forever, like "an ancient song still vibrating," transcending borders, overcoming societal prejudices, and becoming eternal.

There will always be generations of people who see Van Cao as heroic and proud, in the moment they sing in unison.Marching SongThere will also be some people, in the quiet of a lonely night, longing for their homeland, who cannot stop singing.The first spring,To learn to love life and people in quiet solitude.

VI

VI EN

EN