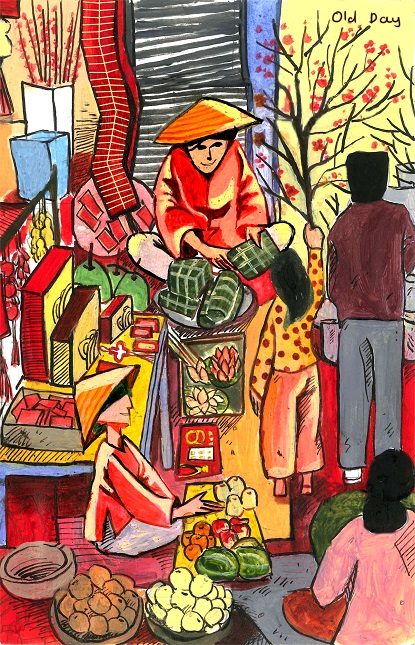

TET MARKET

When I was little, my mother often took me to the market. Of course, I wasn't strong enough to carry the bags or skilled at shopping. My main job was just watching the cart; it wasn't anything particularly glorious.

And for a child, standing still is difficult. So I cycled around the outer market. I preferred watching people display rows of kumquat trees or branches of flowering peach blossoms of varying sizes. In the days leading up to Tet (Lunar New Year), not only were the stalls inside crowded, but the outer ones were equally bustling. From early morning, the women would carry their baskets of goods out and set them up along both sides of the road in front of the market gate.

The makeshift stalls displayed piles of gold coins, colorful plastic flowers, and pairs of green sticky rice cakes. I loved going over to the incense stall to smell the scent. My father often grumbled because I burned too much incense at home, the ashes flying everywhere. But that was just a childish pastime.

He doesn't understand anything.

I no longer sit behind my mother every time we go to the market to buy things for Tet (Lunar New Year). That's a thing of the past, from my childhood days.

My mother usually goes to the Tet market from the 26th to the evening of the 30th. She doesn't buy everything at once, but brings home a little bit of cakes, candies, flowers, and decorations each day. In recent years, she hasn't bought sticky rice cakes anymore. Instead, she makes them herself – flat, square-shaped cakes. I call them "flat squares" because after boiling, they aren't exactly square; they're flattened at one end or the other. Sometimes, the filling even spills out.

For me, Tet markets don't hold many memories. But the feelings I get from those Tet markets remain the same: still exhilarating and exciting.

Another new year has arrived. I will still go to the market with my mother from the 26th to the night of the 30th. We will still argue about what she buys. We will still wrap those "flat, square" sticky rice cakes and burn lots of incense.

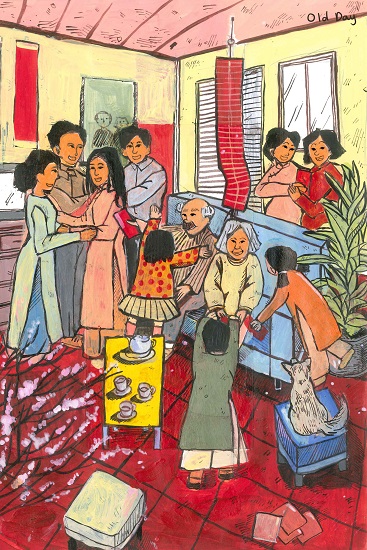

WISH A HAPPY NEW YEAR

NIn recent years, my parents have considered me a grown-up, as I've been able to go and wish neighbors and relatives a happy New Year on my own.

As a child, I often went with my parents to wish people a Happy New Year. My good fortune back then was that I was small, so there was no reason why I'd get a pile of lucky money just from going around the neighborhood. But it wasn't just about wishing people a Happy New Year. I still had to memorize greetings about health, luck, and happiness. And my father seemed proud when the neighbors praised him, saying, "That talkative son of mine." I could only maintain that quick wit for a short while; after that, I lost interest in talking. The adults were too noisy and sat for too long. They drank alcohol and talked about things a child couldn't understand.

As I got a little older, I realized that wishing someone a Happy New Year was not just a custom, but also a way for people to meet and catch up with each other.

And honestly, the older I get, the less I like going to wish people a happy New Year. My parents often complain that when I come home for the New Year, I should visit and wish the neighbors a happy new year. I shouldn't just stay home playing games. But every year I only get questions like "Do you have a boyfriend/girlfriend yet?" "When are you getting married?" "How much is your monthly salary?" Those are boring questions that nobody wants to answer.

A new year is approaching, and I'll be returning to my hometown. I'm no longer the child who loved wearing new clothes, running around receiving New Year's money, and memorizing New Year's greetings. Each stage of life brings changes in my perspective and way of thinking. I'm ready to take over the role of my parents in receiving guests. Ready to offer sincere New Year's greetings and prepared for those "questions no one wants to answer." What about you?

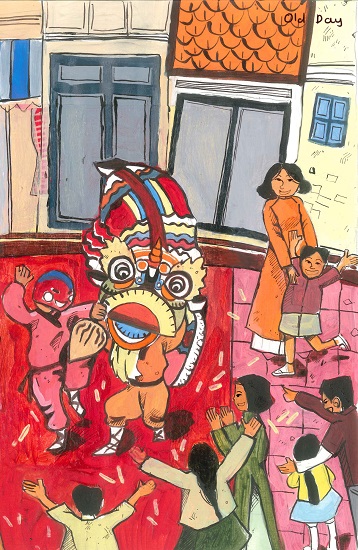

THE DRUM OF CHILDHOOD

Boom, boom, boom...

The sound of drums echoed from somewhere, and I stepped outside to see what was happening. A few houses to my right, emerging from a small alley, were several boys wearing lion masks and dancing enthusiastically in front of the "earth god" figure. The drumming grew louder as more boys with drums gradually emerged from the alley. The boy playing the drums looked incredibly enthusiastic, his hands gesticulating rapidly, his excitement emanating from the drumming and making the "lion" dance with renewed vigor.

And in a certain drumbeat, I suddenly found myself standing in another place. A place where the surroundings felt incredibly familiar, yet also strangely unfamiliar, as if I had been away for too long. It was a spring afternoon, when I followed the children's lion dance troupe through the neighborhood. The incessant drumming and the children's shouts created a commotion wherever they went. The lion dance troupe, with its white and yellow lions, was further accompanied by little boys dressed as Pigsy and Monkey King, wielding their magic staffs. While the lion dance troupe ran into people's houses to perform, other children stood at the end of the alley, surrounding the drum and beating it vigorously. Suddenly, a scout ran up, shouting for everyone to go to someone's house. So the children all rushed there. Some even hoisted the drum onto their shoulders to run faster, others dragged the drum stand with its wheels behind them. Sweat dripped down their faces. As I was engrossed in watching the lion dance perform, its head bobbing back and forth to the rhythm of the drums, a child standing nearby suddenly shouted excitedly, startling me.

The shouts had barely died down when I saw the children rushing towards me, entering the house to perform the first-footing ritual. I gave them lucky money and handed out candies. They thanked me profusely, and just as quickly as they had entered, they all rushed out to "receive blessings" from other houses in the neighborhood. Suddenly, I couldn't control my feet, and it seemed as if they wanted to find their way back to the peaceful days of my childhood. I ran after the children performing the lion dance...

HEY, SIR...

- Oh, there's the calligrapher, Mom!

- How did you know he was a scholar?

- I heard my older sister reciting a poem about the old scholar a few days ago, so I know. After answering, the little girl even babbled a few lines of the poem:

"Every year the peach blossoms bloom"

I see the old scholar again.

Display Chinese ink and red paper.

"On a busy street with many people passing by."

The old calligrapher sat huddled alone in the chill of the early morning on the second day of Tet. The street corner in Hanoi on this spring day was so deserted, so different from the usual days, when it was suffocatingly crowded. His hands were wrinkled, the prominent veins crisscrossing his skin dotted with age spots. Yet, his brushstrokes remained graceful, his elegant calligraphy captivating the viewer's eye.

Having finished writing, he looked up, setting his pen down beside the empty inkwell. His eyes, furrowed with wrinkles, gazed into the distance. At times like these, when the customers had left, his mind didn't move clockwise. He recalled the spring days of decades ago, when, at this very street corner, he and Old Hung and Old Phong sat together.

For a long time, this profession of writing has barely provided enough for people to make ends meet. Old Hung, after clinging to writing for a few years, couldn't bear it any longer and had to return to his hometown. Putting down the pen, he picked up the plow; his small plot of land was enough to provide him with a few meals of porridge and vegetables.

The most unfortunate was old Phong, who had no children. Two years ago, on the afternoon of the third day of Tet (Lunar New Year), in a sudden gust of cold wind, old Phong also passed away. He was already frail, his body so thin that one could see the bones protruding from beneath his skin, which seemed to have no flesh at all. Therefore, whenever the weather changed, he would shiver uncontrollably, wearing several layers of clothing to prevent his brushstrokes from faltering.

Going further back into the past, the calligrapher found himself alongside old Hung and old Phong, busily writing couplets and blessings on red paper. Around them were customers eagerly awaiting their turn. Some were regulars who came to buy from them every year. Others had traveled from afar, having heard of these calligraphers.

"Grandpa!" The little girl's call startled him, the magic of bygone days vanishing. His gaze returned to his stall. The girl, with her clear smile and sparkling eyes reflecting the early year's sunlight, stood before him. He smiled, reciting the final lines of his poem...

"People of the olden days"

Where is the soul now?

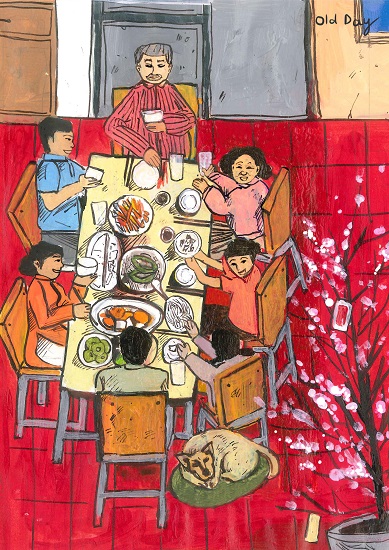

YEAR-END DINNER

Like many other families in this mountainous region, my family had many children. However, also like many other families, we grew up and gradually left our hometown for the city, and my sisters and I only managed to come home for a few days each year.

When I was a student, I could go home twice a year, during the summer and Tet (Lunar New Year). Back then, I would get restless and anxious about going home whenever the end-of-semester exams approached. Due to the nature of my major, I was always the last one to leave.

When I was little, my family held our year-end ceremony very early, around the 25th or 26th of the lunar month. My father would already set up the altar. On those days, I would help sweep and clean the altar, polish the brass incense burners until they shone, and cut flowers to decorate the altar. My sisters would help my mother cook in the kitchen. Back then, our year-end ceremony was very grand; we always invited several tables of guests. My mother said that our family only had one ancestral commemoration a year, so we had to make it big to show our gratitude to our relatives and neighbors.

Since I went to university, my father moved the New Year's Eve ceremony to the very last day of the old year. During those drowsy bus rides, my mother would constantly call, asking where I was: "Dad is waiting for you to come home so the whole family can be together before he performs the ceremony." The moment I stepped through the gate, the altar was already billowing with incense smoke.

In later years, Dad stopped inviting anyone to the New Year's Eve dinner. The last meal of the year was just my sisters and I, vying to eat the dishes Mom cooked and sharing stories about life away from home. Dad wanted to dedicate that rare occasion to being the whole family together.

But the New Year's Eve dinner became increasingly deserted. My sisters-in-law married and moved far away, sometimes coming home and sometimes not, mostly busy cooking at their husbands' homes. I work at the hospital, so while others are on holiday, I'm still busy with syringes and needles, leaving only my parents and my youngest sibling sitting together, looking at each other amidst the steaming hot meal.

On this late afternoon at the hospital, still bustling with patients, I took a quick sip of water between surgeries and read a message from my youngest daughter. My heart ached: "Mom cooked all the dishes my sisters like, but no one came home..."

TRY

My great-grandmother was my maternal grandmother, and my mother's maternal grandmother. There were five sisters in the family, but my mother said I was the only one she had ever cared for since I was little. When she heard my mother was in labor, she grabbed her bag, went to the main road to catch a ride, and traveled dozens of kilometers to carry me. That's why she loved me the most.

Back then, I was young and lived far away, so I rarely visited my great-grandmother. My family was poor; we only had a rickety bicycle, and my parents worked constantly, so several dozen kilometers was a long distance. Usually, only during Tet (Lunar New Year) would my uncle borrow someone's motorbike to take me to visit her so I wouldn't miss her so much.

As soon as he saw me peeking from behind him, Uncle Co stood up, leaning on his walking stick, and hurried out the door. His back was so hunched over that it bent at a right angle, but his eyes were still sharp. He pulled me into his arms, then reached into his belt, took out some loose change, smoothed it out, and patted my head, saying, "Uncle Co is giving you a New Year's gift so you'll grow up quickly." After that, he would go into the room, open the bedside cabinet, and take out the pile of candies and snacks he'd saved all year. Sometimes, there were even peanuts that had been roasted ages ago.

Now, every Tet holiday, I walk up the hill where my great-grandmother rests peacefully, leaning against her. In the distance, the pine forest rustles and the hillside is covered in white reeds.

Grandma, little Chut is back! Still waiting for you to give me lucky money and hug me just like in the old days.

Text and photos: Old Day Team

VI

VI EN

EN