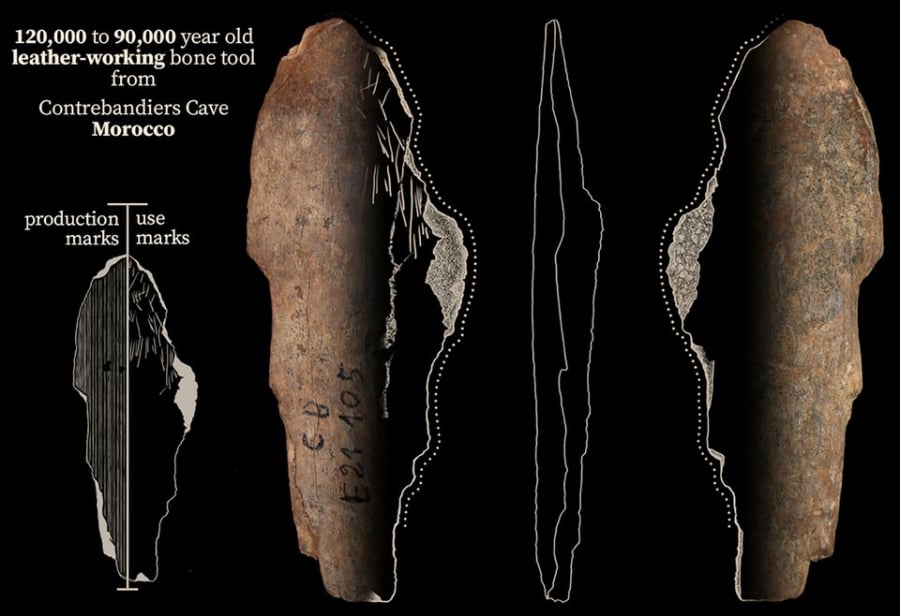

A study led by Arizona State University paleontologist Curtis Marean and Dr. Emily Hallett uncovered 62 tools made from the bones of small carnivorous animals such as foxes, jackals, and lynxes, as well as from the teeth of Cetaceans (including whales, beaked dolphins, and porpoises). These findings, unearthed from the Contrebandiers Cave in Moroccans, provide the earliest recorded evidence of clothing and demonstrate the emergence of sophisticated toolmaking and culture in Africa.

Although the purpose of many of the tools remains unclear, the research team found round, broad objects shaped from animal bones.

Excavations from the Contrebandiers Cave (Moroccan). Photo: Internet

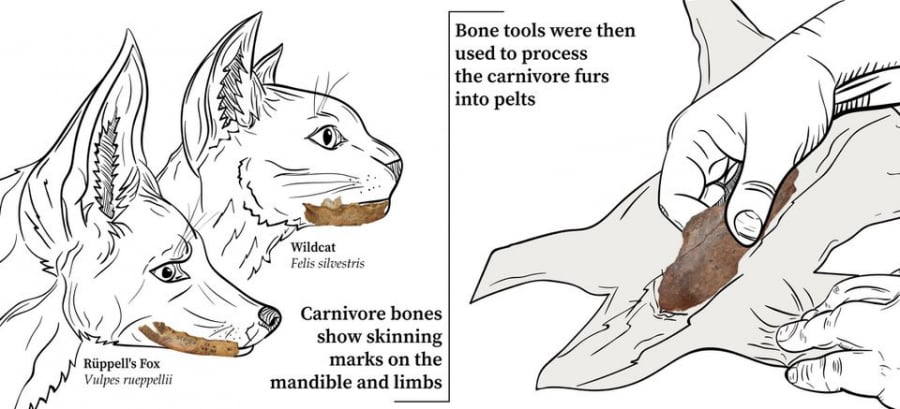

Archaeological artifacts found in the Contrebandiers caves in Moroccans reveal that small carnivorous animals were skinned for their fur and their bones used to make tools. (Illustration: Jacopo Niccolò Cerasoni)

The research team wrote: “These tools are spoon-shaped, making them ideal for shaving, and then removing connective tissue from the skin during the shaving process because they are completely unable to penetrate the skin.”

Dr. Emily Hallett said the work reinforced the view that early humans in Africa were incredibly creative and resourceful. She added: “Our research adds another piece to the list of the earliest human behaviors recorded in African archaeological records from about 100,000 years ago.”

Although animal skins and furs are unlikely to survive in sediments for hundreds or thousands of years, previous DNA-based studies have shown that clothing may have appeared as early as 170,000 years ago and was made anatomically by modern humans in Africa.

The cuts on the bones of sand foxes, jackals, and wildcats are clues related to fur removal. (Illustration: Jacopo Niccolò Cerasoni)

Hallet said she began studying animal bones in 2012 out of interest in early human diets and to find out if any changes in diet were related to changes in stone-making technology.

What these garments actually looked like remains a mystery, with researchers wondering whether they were used as a protective shield against the elements or for some more symbolic purpose.

Hallet added that she believes European Neanderthals and related hominids made clothing from animal skins a long time ago, especially when they lived in temperate and cold environments. “Early human clothing and other tools may have been part of the reason for the success in human adaptation everywhere, even in harsh climates.”

In the future, Hallett hopes to collaborate with other researchers to identify the types of skin peeling and to synthesize information to better understand the origins and scope of this activity.

VI

VI EN

EN