Assisting with sea travel.

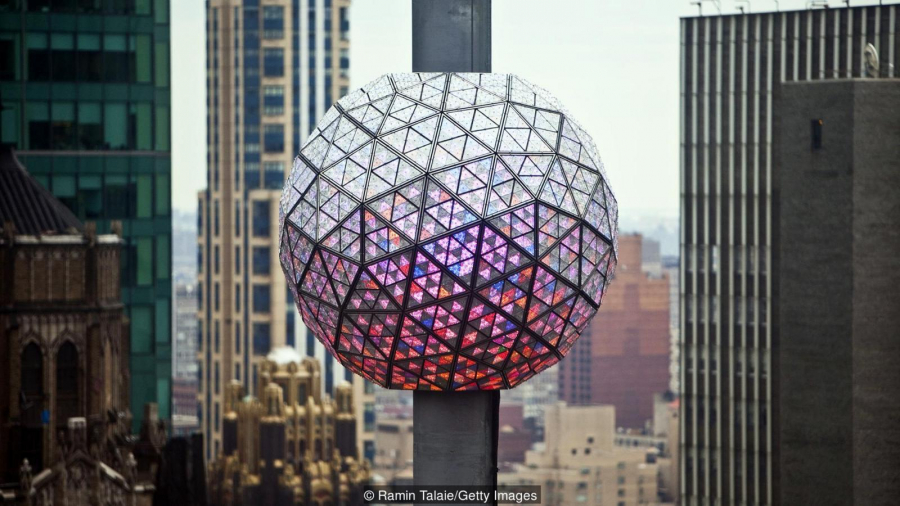

For the final 60 seconds of each year, all attention is focused on the five-ton Waterford crystal ball, sparkling with over 30,000 LED lights that are lowered into the water.

When the ball reaches the bottom of a specially designed flagpole, the Champagne cork will pop open. Then there will be cheers, clinking glasses, and kisses as everyone welcomes a new year full of promise.

An invention dating back to the Victorian era inspired the ball drop ritual in Times Square on New Year's Eve.

But few know of the contributions of the man truly deserving of their praise, a devout Royal Navy officer named Robert Wauchope. Wauchope is credited with creating the time globe, an ingenious Victorian-era machine that inspired the explosion in Times Square. His invention was inspired by seafaring and aimed to make maritime travel safer.

In the early 19th century, knowing the exact time was crucial knowledge for sailors. Only by keeping the clocks on board accurately adjusted could sailors calculate their longitude and navigate precisely across the oceans. Robert Wauchope's globe, first demonstrated in Portsmouth, England, in 1829, was a rudimentary broadcasting system, a way to relay time to anyone who could see the signal.

Typically, at 12:55, a machine would lift a large, painted sphere onto the center of a pole or flagpole; at 12:58, it would reach the top; and precisely at 1:00, a worker would release it to fall back down the pole. "It's a clear signal," says Andrew Jacob, who operates the time sphere at the Sydney Observatory in Australia. "The sudden movement as it begins to fall is easily noticeable."

Greenwich Globe

Before the invention of the time globe, ship captains would often go ashore and visit the observatory to check their clocks against the official time. They would then bring the time back to the ship almost literally. Wauchope's invention allowed sailors to adjust their ship's clocks without leaving the vessel.

"We've become so accustomed to knowing the time here at all times and having ways to tell it, but that wasn't always the case," says Emily Akkermans, who holds the enviable title of "timekeeper" at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London.

The museum and historical site here houses the world's oldest functioning time ball, which has been released daily since 1833, except in cases of strong winds, war, or technical malfunctions.

The Royal Astronomical Observatory in Greenwich, London, is said to have the world's oldest time globe.

Although midday seemed like the ideal time to signal, that was a busy time for the astronomers at the observatory, who had to monitor the sun's position at noon to adjust their clocks. Waiting another hour, until 13:00, would be much less hectic.

The Greenwich globe has inspired hundreds of other globes around the world, from Jamaica to Japan. Globes are often placed on a high point near a harbor, atop an observatory, lighthouse, or tower.

And in just under a century, these time-telling devices have flourished. The idea even took off on land. "It wasn't just for seafaring," Akkermans says. "Some timeballs were operated by watchmakers." In Barbados, a ball dropped at 9:00 to signal the start of classes for students across the island, she notes, quoting an 1888 article in the Illustrated London News. But today, only a few places still have functioning timeballs.

Eighty miles from Greenwich, another time globe is regularly lowered at the coastal town of Deal, near where the English Channel meets the North Sea. This was the first tower connected to Greenwich by an electrical wire, allowing it to relay the official Greenwich time to sailors, although today it relies on signals from British atomic clocks. From April to September, the globe is lowered every hour between 9:00 and 5:00. And it also marks the new year with a special midnight show on December 31st.

Other spheres

Jeremy Davies-Webb, chairman of the Deal Museum Trust, said he knows of four other functioning time spheres besides Greenwich, Deal, and Sydney, although on any given day they could be out of service due to weather conditions or malfunctions. These four spheres are located in Edinburgh, Melbourne, Christchurch, and Gdansk.

He has visited all of those globes except the one in Melbourne, and particularly liked the one in Poland, which marked each release with a resounding trumpet blast. "We'd like to do that, but people near us would complain loudly," he said.

The time globe at the Nelson Monument allows sailors to know the exact time when they are out at sea.

Anna Rolls is the curator at the Clock Museum in London and has worked with the Greenwich time globe for several years. "It's a rather peculiar-looking thing," she admits, a sophisticated mechanism that offers "something easily done today." However, that is precisely what explains its appeal.

In fact, each active time sphere has its own story.

The Greenwich ball, approximately 1.5 meters in diameter and made of aluminum with a surface full of dents, was the result of a misunderstanding. In 1958, staff at the stadium, apparently unaware that the ball had been temporarily removed for repairs, were seen kicking it around the stadium grounds in an unofficial football game.

In Scotland, the time ball at Nelson's Monument was overshadowed by the One Hour Gun fired from Edinburgh Castle. This gun, also intended to signal time to ships, was less accurate than the time ball because sound travels at a relatively slow speed of 1,235 km/h. This meant it took sailors a few extra seconds to hear it.

In Melbourne's Williamstown suburb, the time ball tower has served many different purposes. The square bluestone lighthouse at Point Gellibrand opened in 1849, right during the city's gold rush, but a decade later it was converted into a time ball tower. In 1926, the keeper, who had faithfully launched the ball for 37 years, died, and since no one complained about the discontinuation, it was retired, according to the Australian Lighthouse Preservation Group. Recently, local charities restored the machinery, and the time ball is once again launched daily.

In Lyttelton, New Zealand, the time ball tower collapsed after the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. But a fundraising campaign helped rebuild this magnificent stone heritage structure, and the ball drop resumed in November 2018. It is said that in 1939, German soldiers occupied the upper floors of the Gdansk tower, where they installed a machine gun and fired the first shots, marking the beginning of World War II.

Other inactive time spheres still sit atop buildings around the world, from the waterfront in Cape Town to the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.

New Year's celebration

Regarding its connection to New Year's celebrations, the story begins in 1907. The New York Times had arranged a New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square a few years earlier, marked by gunpowder and fireworks. After authorities banned explosives, the organizers needed something sparkling to mark the New Year, and they found inspiration in the famous time globe of the Western Union Telegraph, which had operated on the roof of the company's Broadway headquarters since 1877.

The New York Times constructed an impressive 700-pound globe and covered it with 100 25-watt light bulbs. But in the spirit of a show, the organizers altered the time globe ritual so that the momentous moment would be when the globe reached its destination, rather than when it was dropped.

Millions of people flock to New York's Times Square to celebrate New Year's Eve every year.

This celebratory stunt was an immediate success. As the newspaper reported the following day: "A loud shout drowned out the whistles for a minute. The sonic power of the celebrants overwhelmed the car horns, bells, and jingles. Above all was the chaotic human noise from which a faint voice emanated: 'Hail 1908!'"

The idea of marking the new year by dropping an oversized object at midnight has since spread around the world. Bermuda released an illuminated onion. In Canada's New Brunswick province, it was a maple leaf; and in Boise, Idaho, it was a potato. But while the ritual of dropping the ball at midnight is gaining traction, the time ball is increasingly disappearing.

A New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square.

By the 1920s, this technology had become obsolete and was quickly replaced by radio, quartz clocks, and now GPS. Most of the time globe towers have been demolished, and the iron machines discarded. "There is no real point in the time globe system now," said Jacob at the Sydney Observatory, which once provided time for the state of New South Wales.

But the astronomer, admitting that he often checks the time on his cell phone, believes it's important to preserve this forgotten daily ritual. "Recreating it every day reminds us that things used to be much more complex and organized than we think. It's fundamental to the state, commerce, international trade," he said.

Today, those who gaze upon the time globe are probably just a few tourists on cruise ships cruising from Sydney Harbour and groups of schoolchildren on field trips.

New Year's Eve globe in New York

However, there was still a certain excitement surrounding dropping the ball to mark the hour. "It made a whoosh and hit the bottom," he said. "It was great fun."

And even if the time-space sphere tower doesn't hold up, this tradition will still stand.

Although Wauchope may have an aversion to boisterous celebrations, by December 31st, his invention will once again take center stage globally, doing exactly what it was originally intended to do: simply and accurately mark the passage of time.

VI

VI EN

EN