On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that Covid-19 had reached pandemic status, with "alarming levels of spread and severity." Almost immediately, international travel came to a halt as countries closed their borders, airlines canceled flights, and cities around the world went into lockdown.

The damage to people's lives, health, and livelihoods continues to mount. The blow to tourism and all those who depend on it is devastating: International arrivals at US airports fell by 98% in April 2020 compared to the previous year, and continued for months. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the global tourism economy is expected to shrink by about 80% when all 2020 data is taken into account.

Nearly a year after the WHO declared a pandemic, the New York Times assesses how some cities heavily reliant on tourism have adapted, including Hoi An in Vietnam.

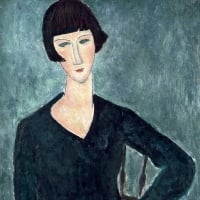

Hoi An in Vietnam, before the Covid-19 pandemic.

With mixed feelings of joy and hope, Mr. Le Van Hung stepped out of his humble home under the coconut trees along the coast of central Vietnam, amidst the sounds of roosters crowing, and took a shortcut to immerse himself in the waves, the sky, and the sun.

The calm sea meant that after months of storms, he could confidently paddle his small boat out to sea to catch crabs and fish to support his family.

Mr. Hung, 51 years old, was a fisherman who spent many years sailing far out to sea on large boats. But he stopped going to sea in 2019 to help his daughter run the restaurant they opened on the beachfront in Hoi An in 2017 amidst a surge in international tourism.

Mr. Le Van Hung on a basket boat

Tourists and much of Mr. Hung's family income vanished when the coronavirus outbreak began in early 2020. And in a devastating blow, a gust of wind swept their Yang Yang restaurant, situated on a sand dune, into the open sea in November.

Now, like many others in Hoi An who have abandoned fishing to join the tourism industry, working as waiters, security guards, or speedboat drivers, or opening their own businesses to serve tourists, Mr. Hung has returned to what he knows best – riding the waves to make a living. This short, hunched man now supports six family members living with him in a few tiled rooms with wooden shutters.

Since September, fierce storms, most recently strong winds and rough seas, have prevented Mr. Hung from going out to sea, fearing his small, bathtub-sized fishing boat would capsize. Looking out at the waves at the end of February, with half of his restaurant's bathroom still lying haphazardly on the beach below, he told himself, "Tomorrow, it will be safe."

Mr. Le Van Hung inspects the new basket boat he bought last August.

So, at sunrise one recent Tuesday, Mr. Hung boarded his boat and braved the rough seas. When he was about 400 yards from shore, on the shimmering emerald-green water, he began casting his nets, encircling a wide area of 500 yards to trap schools of fish.

Mr. Hung grew up in Hoi An, a place that for centuries has been a fishing community nestled between the clear blue sea and lush green rice paddies. Over the past 15 years, Vietnamese developers and international hotel chains have invested billions of dollars in riverside resorts, while locals and foreigners alike have opened hundreds of small hotels, restaurants, and shops in and around the city center. International tourists flock to the area, crowding the beaches by day and spilling into the old town at night.

The pandemic had a more severe impact because Hoi An relies heavily on foreign tourists. In 2019, as many as 4 million out of 5.35 million visitors were from abroad.

After two hours of fishing, Mr. Hung had breakfast while waiting for the sunrise.

Mr. Hung is resting his fishing nets, waiting for the sea to calm down.

The empty nets are causing concern among the fishermen.

When hotels sprang up around Mr. Hung's house on Tan Thanh beach, near the old town, in 2017, his family borrowed money from relatives to buy several dozen sun loungers and umbrellas, and set up an outdoor restaurant on the sand dunes behind their house. His daughter, Hong Van, 23, prepares seafood dishes such as shrimp and squid spring rolls. His two sons help with cooking and setting the table, while he washes the dishes. Mr. Hung completely abandoned his deep-sea fishing team in the summer of 2019, believing that tourism was their ticket to a better life.

"I was very happy at the time," Mr. Hung told the New York Times through an interpreter. "Working from home was truly relaxing mentally and comfortable in daily life with my family."

He earned five times the 3 million dong per month he used to make at sea. However, the restaurant tables were empty as the coronavirus paralyzed Southeast Asia, and Vietnam imposed a lockdown for almost the entire month of April.

Then, Vietnam suffered a second wave of Covid-19 in July, 40 minutes north of Da Nang, just as locals were feeling hopeful about a recovery in domestic tourism. Hoi An remained deserted for many more weeks.

With his savings almost depleted, Mr. Hung knew he had to return to the sea.

It's not just Mr. Hung; many fishermen in Hoi An who abandoned their tourism jobs have had to return to the sea to make a living due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

By August, he was able to propel his small boat through the waves with just one oar. His daughter advertised his catch on her personal Facebook page. But the sea became too dangerous when the 2020 rainy season extended into 2021.

On his fishing boat in a calmer sea, Mr. Hung, wearing a plastic jacket and gloves, began pulling in his net, rolling it into a pile. Occasionally, he would pull out a tiny jellyfish, transparent like a round ice cube, and after another 20 minutes he would catch a silverfish and a small crab, and 15 minutes later another small fish.

Due to the rough seas, Mr. Hung struggled to paddle. He planned to grill the fish instead of frying it to save oil. He hoped to catch a large haul of fish.

"We hope, but I never know what's happening in the deep sea," Mr. Hung confided.

VI

VI EN

EN