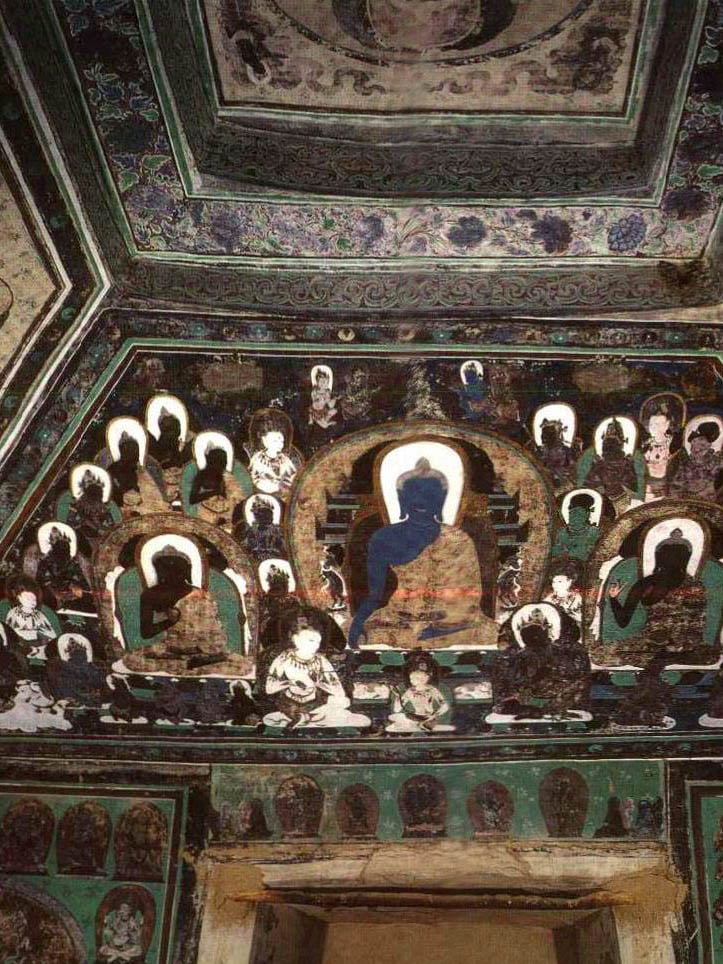

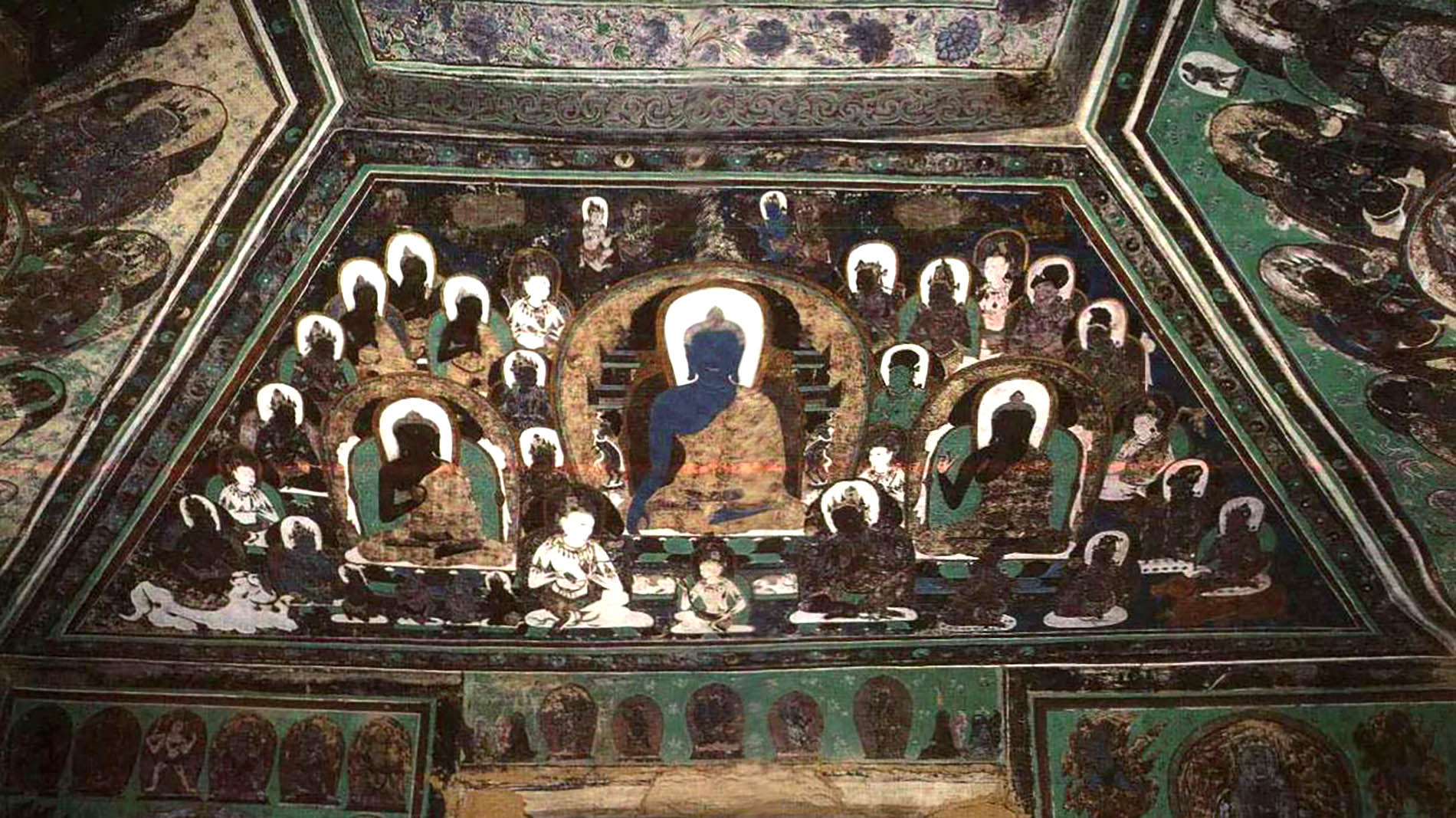

A thousand years ago, there was a series of caves known as the Mogao Caves, located on the edge of the Gobi Desert, near the town of Dunhuang, in western China. This complex was hailed as "the world's most magnificent caves," comprising 492 caves and over 2,400 Buddha statues, along with countless murals, spread across an area of 45,000 square meters.2.

Among them is a room over 150 meters high, containing a massive collection of over 500 books and manuscripts, commonly known as the "Dunhuang Library". It is estimated that the Dunhuang Library houses approximately 40,000 artifacts, including documents, scrolls, oil paintings, silk paintings, and paintings on paper.

But no one knows who, or for what reason, sealed off the entrance to this place, leaving these treasures of knowledge and culture hidden away for 900 years. When discovered and excavated in 1900, the Dunhuang Library was hailed as one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century, even on par with the tomb of Tutankhamun and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

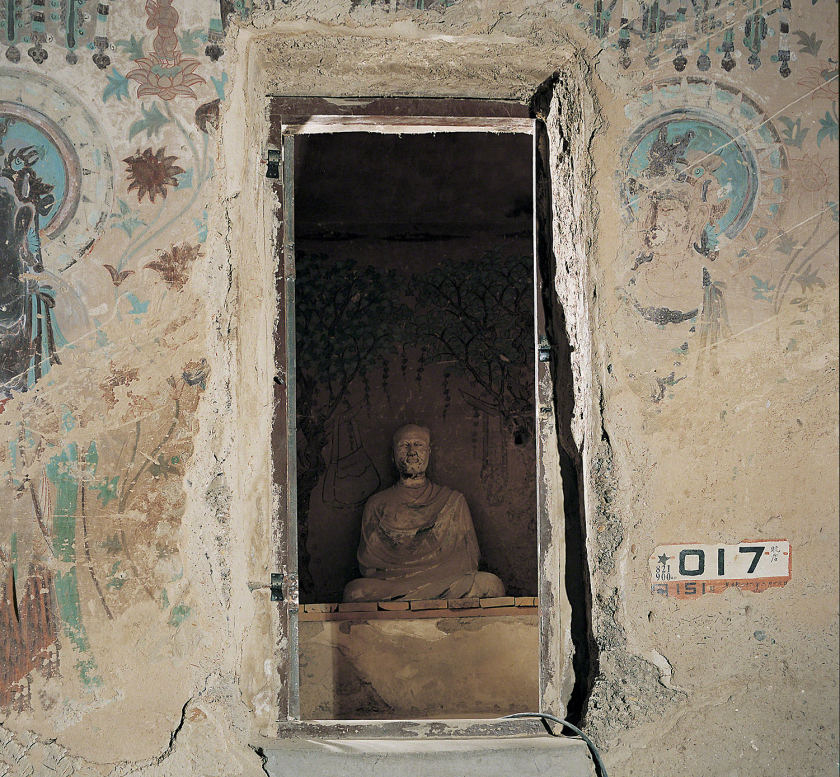

Buddhist statues and murals found in the Mogao Caves complex - Photo: Internet

A serendipitous discovery thanks to… cigarette smoke.

During the Middle Ages, Dunhuang was a thriving city. It was a renowned center of Buddhist worship, attracting pilgrims who traveled long distances to visit the cave temples perched on steep cliffs on the outskirts of the city. However, after the Ming and Qing dynasties, in the early 20th century, the area was engulfed in desert, and the caves consequently fell into disrepair and became desolate.

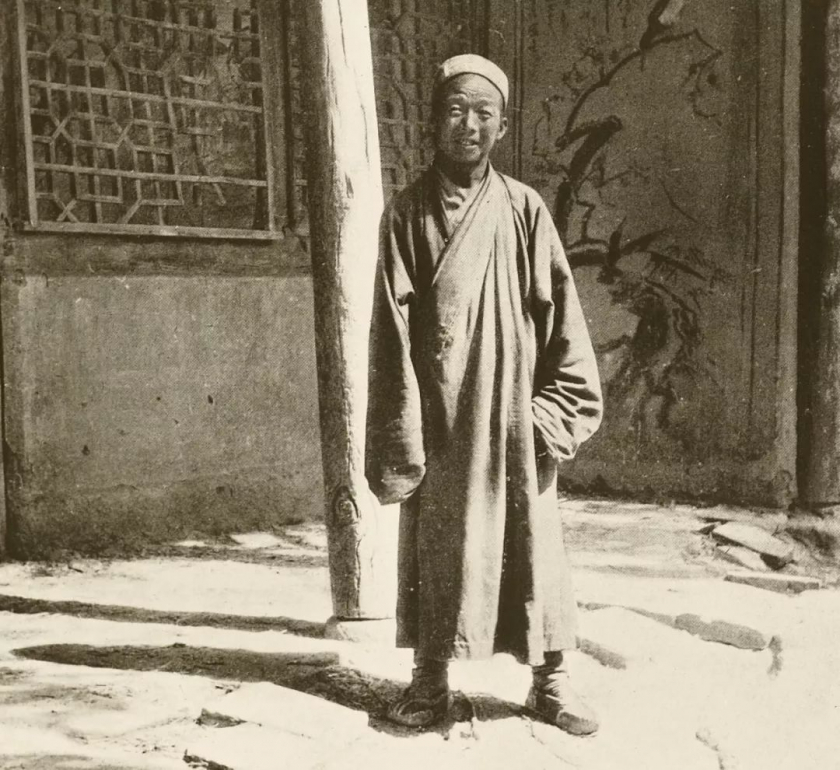

It wasn't until 1900 that a Taoist monk named Wang Yuanlu claimed to be the guardian of the area. One day, while clearing sand, the monk noticed his cigarette smoke drifting towards a large temple located to the north within the cave. There, he found a crack in the wall behind the temple. Curious, the monk tapped the wall and discovered an echo inside, indicating a hollow space behind it. After breaking through the wall, he found a room filled with treasures such as handwritten scriptures, documents, silk paintings, artwork, and religious artifacts, piled up several meters high.

The entrance to the Dunhuang Library is blocked by a wall.

Murals, inscriptions, and ancient documents have been found in the Dunhuang Library.

Although he couldn't read the ancient texts, Wang Yuanlu knew he had found a valuable archive. He immediately contacted local officials and requested that the documents from the secret room be sent to Beijing for research. However, at that time, the city was short on cash and preoccupied with the Boxer Rebellion, so his request received no support.

Photo of Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu - Image: Internet

However, news spread quickly thanks to caravans in Xinjiang. One of the first to hear of this sensational discovery was the Hungarian Indologist and explorer Aurel Stein, who was then undertaking his second archaeological expedition in Central Asia. Stein rushed to Dunhuang and waited for two months to meet the Taoist master Wang Yuanlu at the site where the treasures were found.

The Taoist priest Wang agreed to meet Aurel Stein, but he was very cautious, unwilling to let any documents escape his sight, and quite annoyed when Stein mentioned buying them. Stein promised that he would use these valuable documents to follow in the footsteps of Xuanzang, the monk who embarked on a pilgrimage to India in the 7th century and is the protagonist of Journey to the West. Finally, the priest Wang was convinced and agreed to sell Stein some of the ancient documents and scrolls for 130 pounds.

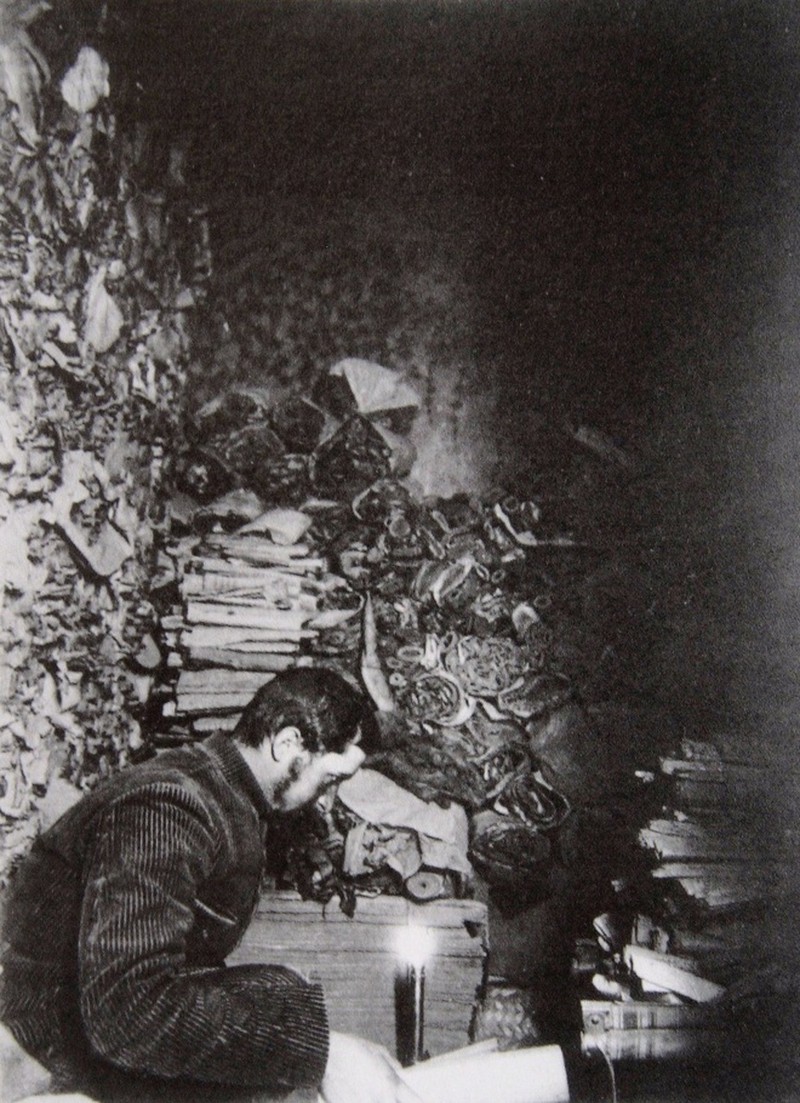

French expert Paul Pelliot searches through documents at the Dunhuang Library in 1908 - Photo: The Musée Guimet

News of the Dunhuang Library ignited a fierce competition among European powers to hunt for Eastern treasures. Following Stein was Paul Pelliot, a French sinologist. Pelliot stayed up all night reading scriptures at breakneck speed by candlelight, then took some of the most valuable items from the library. Thus, foreign expeditions from countries like England, Russia, Hungary, and Japan flocked to the Mogao Caves in search of treasures. By 1910, when the Chinese government ordered all artifacts moved to Beijing, only about one-fifth of the original collection remained.

"Dunhuang Studies" - From a hidden library to a worldwide academic discipline.

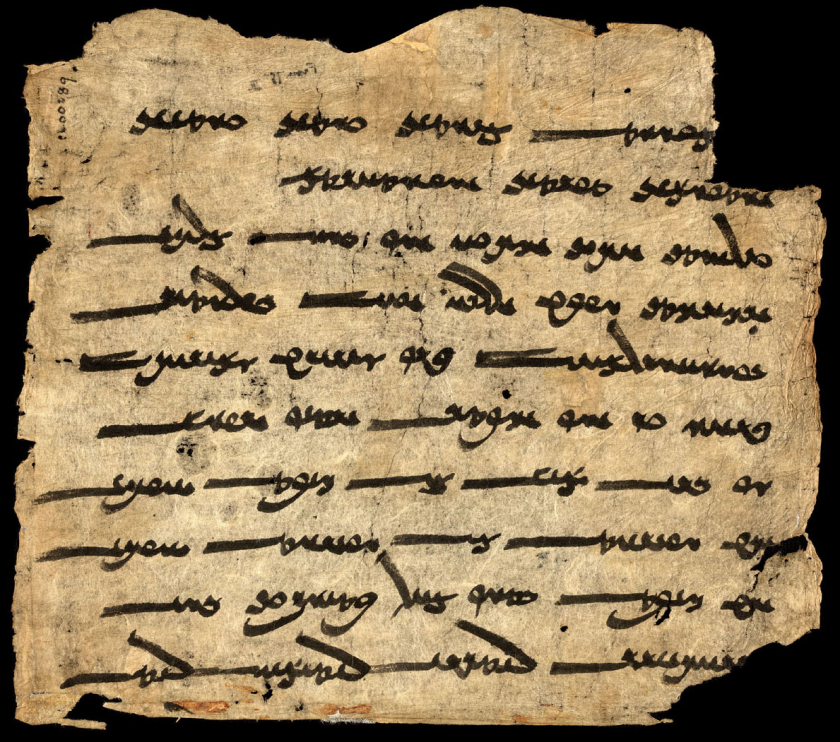

The Dunhuang Library contains thousands of documents recorded in at least 17 languages and 24 scripts – many of which were thought to have been lost forever centuries ago, or are only mentioned in a few ancient records.

These documents preserve the cultural and historical heritage of Dunhuang itself, dating back to the distant days when Buddhists stood shoulder to shoulder with followers of Manichaeism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Judaism. Among them are many scriptures copied by the Chinese from Tibetan prayers translated from Sanskrit. Because of this vast diversity, scholars agree that the research methodology should be equally comprehensive and diverse.

However, for several decades, researching and sharing academic findings from the Dunhuang Library faced numerous difficulties, as Stein and other treasure hunters of the time dispersed the Library's assets, which ended up in dozens of libraries and museums around the world.

Paintings depicting two goddesses of the Sogdiana civilization, in the Dunhuang Library.

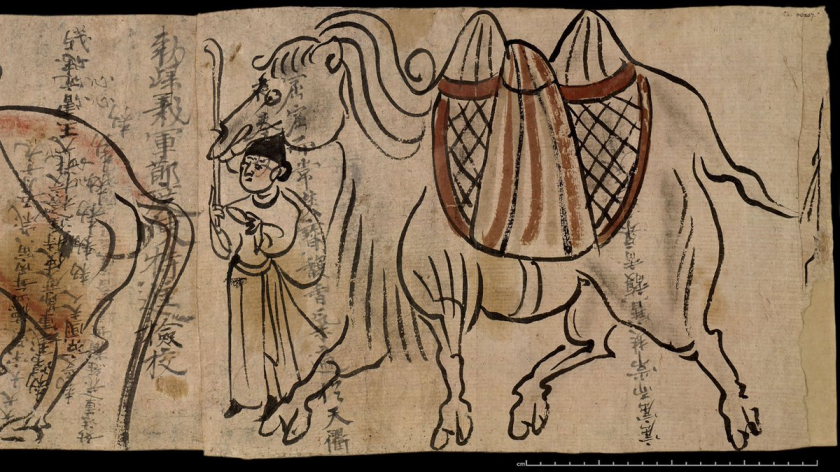

The painting depicts a camel.

Since 1994, a global digitization program has been established, allowing scholars and researchers to reconstruct individual documents they possess and then upload them to the program. There, the content of many Dunhuang projects is stored, discussed, and preserved for future generations.

Thanks to digital tools and modern technology, many documents have been restored, protected from corrosion, and photographed for archival purposes. From these, researchers have been able to read many valuable (and fascinating) records from thousands of years ago: the Diamond Sutra – one of the earliest teachings of the Buddha; a prayer written in Hebrew by a merchant on his way from Babylon to China; a contract for the sale of a girl as a slave to pay off a silk merchant's debt; a page on divination written in Turkish Rune; and the earliest complete astrological map in the world...

The documents and scriptures found in the Dunhuang Library are also applied to the study of culture, history, religion, and their formation and blending in Asia via the Silk Road. At the same time, they helped to discover the development of paper and printing in China. It turns out that printing began as a form of copying for prayer, as the Buddha taught that the merit accumulated from reading and reciting scriptures is worth more than gold, silver, and jewels.

Printing began as a form of prayer-making, as the Buddha taught that the merit accumulated from reading and reciting scriptures is worth more than gold, silver, and jewels. - Photo by Jin Xu

However, to this day, there remains no definitive answer to the greatest mystery of the Dunhuang Library: what was its original purpose, and why was it sealed away? Based on the inscriptions in the surviving documents, it can be inferred that the library's former caretaker was the monk Hongbian, who led the Buddhist community in Dunhuang. In 862, after his death, his statue was erected inside a temple within the Mogao Caves complex. During the Western Xia dynasty's rule over Dunhuang (after 1049), the monks of the Mogao Caves, seeking refuge, placed the historical treasures in this room, which was then sealed off by a wall. After the war ended, none of the monks returned, and the room became a secret, unknown to anyone. According to researchers, this is the most plausible hypothesis explaining why the Dunhuang Library remained sealed for nearly 1,000 years.

Statue of the monk Hongbian - Photo: Dunhuang Academy

Today, an entire academic discipline has formed around the documents it houses, known as Dunhuang studies. Scholars worldwide conduct extensive research on it, and numerous world-scale Dunhuang conferences have been held. However, studies also reveal alarming facts about the environmental situation surrounding the Library in particular and the Mogao Caves complex in general, as desert sand is constantly being blown in, threatening the area's survival.

VI

VI EN

EN