From village to city, and back again.

My name is Trang Vuong, I'm 27 years old, born and raised in Phuc Sen - a place in Quang Hoa district, Cao Bang province, which preserves many long-standing cultural traditions. Besides established craft villages like Phia Thap incense village or Dia Tren paper-making village, Khao hamlet, where I was born, also has the traditional weaving and indigo dyeing craft of the Nung An people. This craft has existed for a very long time, closely linked to the lives of many generations.

Weaving and indigo dyeing are traditional crafts that embody the hard work and finesse of women in the highlands.

I studied tourism and had the opportunity to travel to many places and encounter diverse cultures. It was through these trips that I gradually realized that my homeland possesses unique values, second to none, though fewer people preserve and share them. Therefore, I decided to return and contribute a small part to preserving and promoting the traditional crafts of my people. For me, weaving and indigo dyeing are not just means of livelihood, but the very soul of an entire community.

I decided to return to Phuc Sen in April of this year and began learning the craft from the women in the neighborhood. Initially, it seemed simple, but only when I actually started did I realize how arduous the profession is. From spinning yarn and weaving fabric to soaking and fermenting indigo dye and drying each batch of cloth in the sun, every step requires patience and precision. The more I learned, the more I was drawn to this meticulousness. Sometimes, I lost track of time sitting beside the fermenting indigo vat, inhaling that pungent smell that felt strangely familiar.

Having left her village for the city, Trang has now returned to her hometown, following in the footsteps of her grandmother and mother in preserving the traditional indigo dye of her ethnic group.

From white cotton to indigo hues woven from earth and dried in the sun.

The indigo dyeing craft in Phuc Sen has been closely linked to the lives of the Nung An people for hundreds of years. This is not the industrial indigo that can be bought from elsewhere, but rather handcrafted indigo, made entirely by hand: from planting the indigo plant, soaking and fermenting, filtering the residue, to harvesting the indigo extract, curing and nurturing the indigo, dyeing the fabric, and drying. Each stage requires time, effort, and unwavering dedication to the craft.

The indigo dyeing craft of the Nung An people begins with two things: cotton and indigo dye. Cotton is grown in the fields, harvested, dried, the seeds are removed, and then spun into yarn. The villagers use wooden looms to hand-weave each row of fabric. The finished fabrics are then dyed.

Indigo is a plant that takes almost a year to harvest. When the time is right, the plants are cut and soaked in a stone trough for two days and two nights to allow them to decompose, creating an indigo paste. This paste is then filtered and mixed with lime water to form a mixture called indigo – the main ingredient for dyeing fabric.

White fabric is dyed with indigo for about a month. Each day, a small bowl of indigo paste must be added to the vat and stirred thoroughly. This must be done regularly to keep the indigo active and allow the color to penetrate deep into each fiber. When the fabric changes from white to blue, then dark blue to charcoal purple, the color is "ripe." But to achieve that color, it must be dyed repeatedly, eighty or ninety times, several times a day; there's no rushing, and no sloppiness.

The process of dyeing and drying the fabric with indigo takes almost a month to produce the perfect, beautiful indigo color.

On gloomy, damp, and cold days, I get impatient because the fabric won't dry. And if it doesn't dry, I can't continue dyeing the next day. The weather is like an unpredictable partner for indigo dyers; it's either favorable or it ruins an entire batch of fabric.

Phuc Sen indigo is also special because its blue color is deep, not dazzling, but durable, mellow, and becomes more beautiful with use. To maintain that color, the craftsman must be patient and understand the characteristics of each batch of indigo, each thread of fabric, the humidity of the weather, and even the drying speed in the sun.

A traditional Nung An costume requires about 10 meters of fabric. Indigo fabric sells for 100,000 to 150,000 VND per meter, but its value lies far more in the effort put into it and the story woven into it.

Phuc Sen indigo is also special because its blue color has depth, is not bright or flashy, but is durable, mellow, and becomes more beautiful with use.

Preserve the soil's color, preserve the people's traditional crafts.

The old Phuc Sen commune was home to only one ethnic group: the Nung An people. Through many ups and downs, the people here have preserved their traditional crafts: from knife making and incense production to indigo weaving. Amidst the changing urban landscape, more than 10 households continue the craft, mainly in small hamlets like Khao. For the Nung An people, indigo fabric is not just for clothing. It's wedding attire, festive attire, and a spiritual item. Some say, "A beautiful piece of indigo fabric not only shows skill but also reflects the moral character of a Nung An woman." Hearing that, I felt both proud and pressured, because those who preserve the craft today must not only weave the fabric but also continue to weave that spirit.

I started experimenting with new products made from indigo fabric: handbags, scarves, dresses, shirts – items that appeal to young people. I also created a small space in the backyard where visitors can come and touch the fabric themselves, try dyeing it once, and smell the real indigo to understand the craft not just visually, but through experience. I believe that if the craft is preserved properly and creativity is continuously fostered, handcrafted products will never go out of style. On the contrary, they carry a story, and whoever holds one of these products also carries a piece of Phuc Sen's memory.

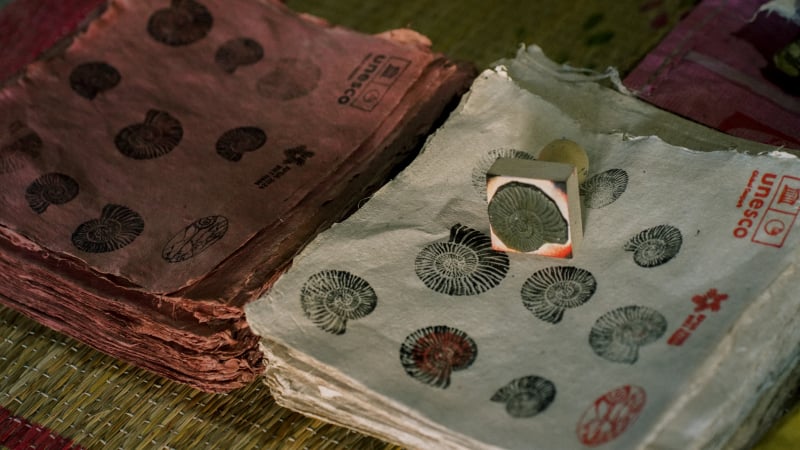

Visitors come to experience spinning yarn and weaving fabric at Trang's house.

By experimenting with new products like hats and bags, Trang hopes the story of indigo fabric will be shared with visitors from afar.

Life here lacks the familiar coffee shop I frequent after work, and the gleaming glass buildings. But I have a garden, indigo plants, and a small porch where I dye and dry my fabric. There, day after day, I repeat the seemingly simple tasks that are weaving a journey: the journey of preserving the indigo color of my homeland.

VI

VI EN

EN