Despite enduring countless wars throughout its history, Vietnam remains a treasure trove for scientists. According to research, Vietnam is one of the world's most attractive destinations for biodiversity. With an area only slightly larger than the state of New Mexico, Vietnam boasts 30 national parks, home to an incredibly diverse and abundant array of flora and fauna, rivaling even the safaris of Kenya or Tanzania.

In fact, hundreds of new plant and animal species have been discovered in Vietnam over the past three decades, and that number increases every year. Take the saola, for example. Its gentle face looks as if it just stepped out of a painting by Henri Rousseau, and it's nicknamed "the last unicorn" because of its rarity. The saola is the largest new land animal discovered since 1937. Many animals, such as the muntjac, the striped rabbit, and the giant stick insect, thought to be extinct, have been rediscovered in Vietnam. Vietnamese forests are home to dozens of primate species, gibbons, long-tailed monkeys, slow lorises, and langurs, all in vibrant colors.

Vietnam has as many as 30 national parks, home to an incredibly diverse and abundant variety of flora and fauna.

Environmental researcher Stephen Nash shared that he received an email advertising Cuc Phuong National Park, which included the following passage: "This ancient forest is home to nearly 2,000 plant species, and scattered throughout it are rare and unique animals such as clouded leopards, white-legged langurs, northern civets, otters, sun bears, owls, flying squirrels, slow lorises, bats, and various species of wild cats..."

However, when he and his wife expressed their desire to experience the wild nature here, the travel agency was strangely hesitant to discuss the topic, and instead tried to persuade them to switch to resorts with simply beautiful scenery or locations within the city.

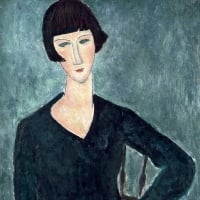

A large heron species found in Vietnam.

The reason is that the primary forests are no longer "prime." Wildlife, already struggling with destruction and habitat loss caused by humans, now face the added risk of being shot or trapped. This has led many national parks and nature reserves to face the "barren forest syndrome"—occurring when forests are devoid of animals. Besides Vietnam, many other Asian countries are facing a similar situation. In fact, many species may disappear before scientists even discover them.

Vietnam's biodiversity decline is at an alarming rate. For example, in a national reserve for saola and other rare animals, 23,000 deadly traps were found in 2015 (the most recent update). Tens of thousands more traps are set each year, and the rate of additions is as fast as the rate of discovery and seizure. Therefore, despite tireless searching and surveying, not a single saola has been found since one individual was captured on camera in 2013. The last rhinoceros was shot dead by illegal poachers in Cat Tien National Park in 2010. Tigers are also being pushed to the brink of extinction. Only small groups of bears and elephants remain. The threat of extinction hangs over almost all primate species.

Many bears are held captive, their bile is extracted, and their paws are cut off to serve the "luxury" needs of humans.

Some species are hunted for processing into tonics according to Eastern medicine beliefs, such as in Vietnam and China. Some of the "uses" listed in the catalog of these "products" from the forest include: tiger penis for erectile dysfunction, bear bile for cancer, rhinoceros horn for hangover relief, and slow loris bile for respiratory infections caused by air pollution...

Despite wildlife conservation campaigns, "the demand for bushmeat is increasing, rampant in specialty restaurants in cities, and has become a status symbol," said Barney Long, Director of Conservation at Global Wildlife Conservation. "This isn't about starving people hunting for meat," he continued. "It's a 'fancy' way to treat colleagues and business partners to drinks. This is a horrifying reality. What we're worried about isn't the loss of a few species, but the potential extinction of all animal species."

After doing some more research, Stephen Nash remained determined to embark on a journey to explore the wildlife of Vietnam, in both the North and South.

He witnessed firsthand the extent to which animals are threatened during this two-week trip. He also directly observed the relentless struggle of Vietnamese people, as well as like-minded foreigners, to combat the "animal genocide."

The langurs at the Center for the Rescue of Endangered Primates

A red-footed langur in Cuc Phuong National Park.

Cuc Phuong is Vietnam's first national park, located just a few hours' drive south of Hanoi. It was established by President Ho Chi Minh in 1962. "Forests are gold; if we know how to protect and develop them, they are invaluable." However, upon arriving, Nash didn't see a single langur, bear, leopard, or small wildcat. Perhaps they've hidden so well that even scientists can't find them, as Adam Davies, Director of the Endangered Primate Rescue Centre, put it.

It turns out that instead of living in the wilderness, these rare animals are residing in rescue centers.

With its distinctive five colors, the red-footed langur, also known as the five-colored langur, is honored by international wildlife conservation organizations as the "queen" of primates residing in the deep forest due to its extraordinary beauty.

At the Endangered Primate Rescue Centre, visitors can see four nearly extinct species of langurs (also known as leaf-eating monkeys), gibbons, and slow lorises. Many of them have been rescued from illegal wildlife traffickers. They are being rehabilitated, bred where possible, and, if a miracle happens, they might be able to return to the wild. "Poachers have made the national park so dangerous that there are hardly any species left to survive," said Davies.

That's where the other two rescue centers are located. One center is protecting dozens of rare turtle species, many stunningly beautiful, all endangered. The second center is for leopards, civets, palm civets, and pangolins, all rescued from illegal trade, with pangolins being the most frequently caught for their scales and meat. Pangolins sell for over $1,000 a kilogram in restaurants or traditional medicine shops in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Mr. Davies sadly remarked, "Pangolins are currently the most trafficked mammal in the world. Perhaps no species likes that title."

A red-eared turtle is being cared for by experts at the conservation area of Cuc Phuong National Park.

Many wildlife species in Cuc Phuong National Park are at risk of disappearing.

Davies' center has rescued several critically endangered white-legged langurs in the Van Long Nature Reserve and helped them reintegrate into the wild. The langurs are reproducing somewhere deep within the reserve. Nash spent an entire hour watching the langurs grooming themselves, chasing each other, and sunbathing in the intense subtropical heat. Fortunately, they will continue to be protected here, not becoming targets for poachers or the pet trade.

Not far from Cuc Phuong National Park are Bich Dong Pagoda and Tam Coc, home to many species of birds.

To see bears with her own eyes, Nash went to Tam Dao National Park, located on a long mountain slope north of Hanoi. The bear sanctuary there is operated and managed by Animals Asia and occasionally opens to visitors. Nash was able to watch sun bears and moon bears playfully frolicking, swimming, and climbing in their own designated relaxation area. Both looked like playful versions of the North American black bear with their distinctive white collars. The bears were brought here from bear farms, where they were kept in enclosed spaces, repeatedly subjected to bile extraction until... they were no longer fit to live.

This practice is illegal, but loopholes in the system make it very difficult to enforce justice. Tuan Bendixsen, director of the Vietnam Bear Rescue Center, stated, "Illegal bear bile harvesting is still ongoing. You can still find it for sale in Hanoi if you want."

Many of the bears rescued by Bendixsen's center have lost legs or suffered various other injuries, making their chances of returning to the wild even slimmer. And with population and economic growth, the pristine areas suitable for releasing them back into the wild are shrinking.

Murphy, a male sun bear at the Bear Rescue Center in Tam Dao National Park.

Nash visited another nature reserve in Ninh Binh. Called an "eco-destination," the entire area had been acquired by a tourism company and was undergoing development. Trees in the forest were being mercilessly cut down, depriving birds of their habitat. Drills, chainsaws, and bulldozers were busily working on a project to expand a lakeside resort; had any consideration been given to preserving the birds' living space?

After about ten minutes of boating on the tranquil lake, Nash began to hear a cacophony of squawks, like a group of people arguing. The boat pulled up close to a rocky shore, and hundreds of herons and egrets, each as large as a two-year-old child, swarmed overhead. Their future still depended on the construction project, on whether this calm and seemingly pristine lake would suffer the consequences of the surrounding environmental changes.

The future of birds and wildlife in the Thung Nham Bird Garden Ecotourism Area may depend on a construction project in the region.

In the South, Nash visited Cat Tien National Park, about 150 km from Ho Chi Minh City. A young guide took him on a two-hour trekking trip through the wilderness. It was truly a tranquil forest. The only animals he encountered were leeches.

The Island of Immortals, a center for the rescue of endangered primates, is located on a nearby island. Here, visitors can admire primates, including gibbons, swaying in the tall trees and listening to their sometimes deafening "chorus." Some of them have been shot and trafficked to the city for their meat.

Many conservation organizations are struggling in the fierce battle against "animal genocide" in Vietnam and around the world.

However, Vietnam's forests can still place their hopes in courageous and innovative government and private organizations like the Education for Nature Center. Undeterred by danger, they have been working tirelessly to collect data, conduct research, investigate, and advocate for wildlife.

Facilitating local community participation in wildlife conservation, coupled with economic incentives, is also a promising approach. For example, WWF is funding sustainable rattan and acacia cultivation models for farmers, while other organizations pay people to participate in forest guarding and collecting animal traps.

“Every day we wake up and ask ourselves: Do we have enough time to conserve wildlife? Have we already lost this battle?” said Quyen Vu, Executive Director of the Center for Nature Education. “But if we don’t fight, we will surely lose everything!” she asserted.

VI

VI EN

EN