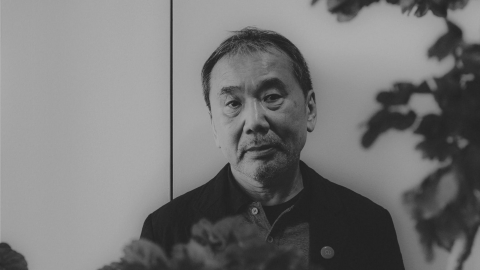

This is a translated excerpt from Haruki Murakami's short story "Leaving a Cat Behind," written in honor of Father's Day 2022, originally translated into English by Philip Gabriel for The New Yorker magazine.

Of course, I have many memories of my father. Naturally, we lived together under one not-so-spacious roof from the time I was born until I left at eighteen. And, like most children and parents, I assumed some of my memories of my father were happy, others not so happy. But it turns out that the fragments of memory that remain most vivid in my mind fall into neither of those categories; they contain more ordinary events.

For example:

When we were living in Shukugawa (a district of Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture), one day we went to the beach to abandon a cat. I can't remember why we had to abandon it. It wasn't a kitten, but an adult female cat. Our house at the time was a single-family home with a garden and plenty of space for cats. Maybe it was a stray cat we picked up, and then it got pregnant, and my parents felt they couldn't take care of it anymore. I don't remember exactly. Back then, abandoning cats was normal; nobody criticized it. Nobody thought about spaying or neutering cats. I had just started elementary school at the time, I think, so it was around 1955, or a little later.

My father and I set off one summer afternoon to leave the cat by the seashore. He rode his bicycle, and I sat behind him, clutching a box containing the cat. We rode along the Shukugawa River to the beach in Koroen, laid the box down among the trees, and returned home without looking back. That beach must have been about two kilometers from my house.

Back home, my father and I got out of the car—talking about how guilty we felt about the cat, but what else could we do?—and opened the door. The cat we'd left on the beach was sitting there, meowing a friendly "meow," its tail held high. It'd gotten home before us. I couldn't imagine how it'd done that. We were on bikes, after all. My father was bewildered too. We stood there for a while, not knowing what to say. Gradually, my father's astonished expression turned to admiration and finally, to relief. And we adopted the cat again.

Another memory of my father

Every day, before breakfast, my father would sit for a long time in front of the Buddhist altar in our house, intently reciting scriptures with his eyes closed. To be precise, it wasn't an ordinary Buddhist altar, but a small, cylindrical glass cabinet containing an exquisitely carved statue of a Bodhisattva.

Clearly, this was an important ritual for my father, a ritual that marked the beginning of the day. From what I knew, he never forgot to perform what he called his "duty," and no one was allowed to disturb him. It wasn't simply a "daily routine."

Once, when I was a child, I asked my father who he was praying for. He replied that he was praying for those who had died in the war—Japanese soldiers and even Chinese soldiers who had been their enemies. My father didn't elaborate, and I didn't press him. I thought that if I had pressed him, he might have opened up more. But I didn't. There must have been something preventing me from continuing the conversation.

When my father was a young boy, he was sent to apprentice at a temple somewhere in Nara. With his understanding, he should have been adopted into a Nara monastic family. However, after his apprenticeship, he returned home to Kyoto. The reason given was that the cold had negatively affected his health, but the main reason was probably that he couldn't adapt to the new environment. After returning home, my father continued to live like a son to his parents, just as before. But I have a feeling that the experience didn't heal in him; it became a deep emotional scar. I can't point to any concrete evidence for this conclusion, but there's something about my father that makes me feel this way.

I now recall the expression on my father's face—initially astonishment, then admiration, and relief—when the cat we had left on the beach came home before us.

I've never experienced anything like it. I must say I was raised very affectionately, as an only child in a middle-class family. Therefore, I couldn't understand, either practically or emotionally, the extent of the emotional scars left on a child by being abandoned by their parents. I could only vaguely imagine it.

My father was born on December 1, 1917, in Awata-guchi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto. When he was a child, the peaceful Taisho democratic era was coming to an end, followed by the grim Great Depression, then the quagmire of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and finally the tragedy of World War II. This was followed by the turmoil and poverty of the early post-war period, when my father's generation struggled to survive.

Shortly after my father was discharged from the army, World War II broke out in the Pacific. If he hadn't been released then, if he had been deployed with his old unit, he almost certainly would have died on the battlefield, and of course, I wouldn't be here now. You could call it luck, but surviving while all his former comrades perished became the root of his immeasurable pain and suffering. Now, I understand even more why he closed his eyes and focused on reciting Buddhist prayers every morning for the rest of his life.

My father always loved literature, and after becoming a teacher, he devoted much of his time to reading. Our house was filled with books. This probably influenced me in my childhood, as my passion for reading grew within me. My mother often told me, "Your father is very intelligent." How intelligent he was, I don't know. To be honest, it wasn't a question that concerned me much. In my field of literature, intelligence wasn't as important as a keen intuition. That may be true, but the fact remains that my father always excelled in school.

Compared to him, I've never had any interest in studying. My grades have been lackluster from beginning to end. I'm the type of person who eagerly pursues what interests me and doesn't bother with anything else. That was true when I was a student, and it's still true now.

This disappointed my father, and I'm sure he compared me to himself at the same age. "You were born in peacetime," he must have thought. "You can study as much as you want, nothing can stop you. So why can't you try harder?"

I think my father wanted me to follow the path he couldn't take because of the war. But I couldn't live up to his expectations. I could never force myself to study the way he wanted. I found most of the classes at school mind-numbing, the school system too rigid and harsh. That deeply disappointed my father, and I suffered from persistent anguish (and unconscious fits of anger). When I became a writer at thirty, he was very pleased, but by then our relationship had quickly become distant and cold.

As I grew up and developed my own personality, the animosity between me and my father became more apparent. Neither of us was willing to compromise, and when we could no longer directly express our thoughts to each other, we became completely different people. For better or worse, it was the same.

After I got married and started working, my father and I grew increasingly distant. By the time I dedicated myself full-time to my writing career, our relationship had become so strained that we almost completely cut off all contact. We hadn't seen each other for over twenty years and only spoke when absolutely necessary.

My father and I were born in two different eras and environments; our ways of thinking and perceiving the world were vastly different. If, at some point, I had tried to mend the relationship, things might have gone in a different direction. But I was too focused on what I wanted instead of trying to achieve it.

My father and I finally spoke to each other directly, not long before he passed away. I was nearly sixty, and he was ninety. He was in a hospital in Nishijin, Kyoto. He had severe diabetes, and cancer was ravaging almost his entire body. He used to be robust, but now he was emaciated. I almost didn't recognize him. And there, in the final days of his life—literally the last days—my father and I managed to have an awkward conversation and reach a state of reconciliation. Despite our differences, I felt a connection, a bond, in seeing my father so frail.

Even now, I can still recall the awkwardness between my father and me that summer day, when we cycled together to the beach in Koroen to leave a tabby cat behind. I can remember the sound of the waves, the scent of the wind rustling through the pine trees. It is the accumulation of such small things that has shaped me into the person I am today.

In any case, there is only one thing I want to present here. One self-evident truth:

I am an ordinary son of an ordinary man. Obviously, I know that. But, when I first began to discover that truth, I realized clearly that everything that happened in my father's life and mine was purely coincidental. We live our lives this way: viewing things that happen by chance and randomness as the only reality.

To put it another way, imagine raindrops falling on a vast expanse of land. Each of us is an unnamed raindrop among countless others. Naturally, we are individual, independent drops, but entirely replaceable. Even so, that solitary raindrop still possesses its own emotions, its own history, and the responsibility to carry that history. This is true even when it loses its individual integrity and is swept into something collective. Or perhaps, more accurately, because it is absorbed into a larger, more all-encompassing entity.

VI

VI EN

EN