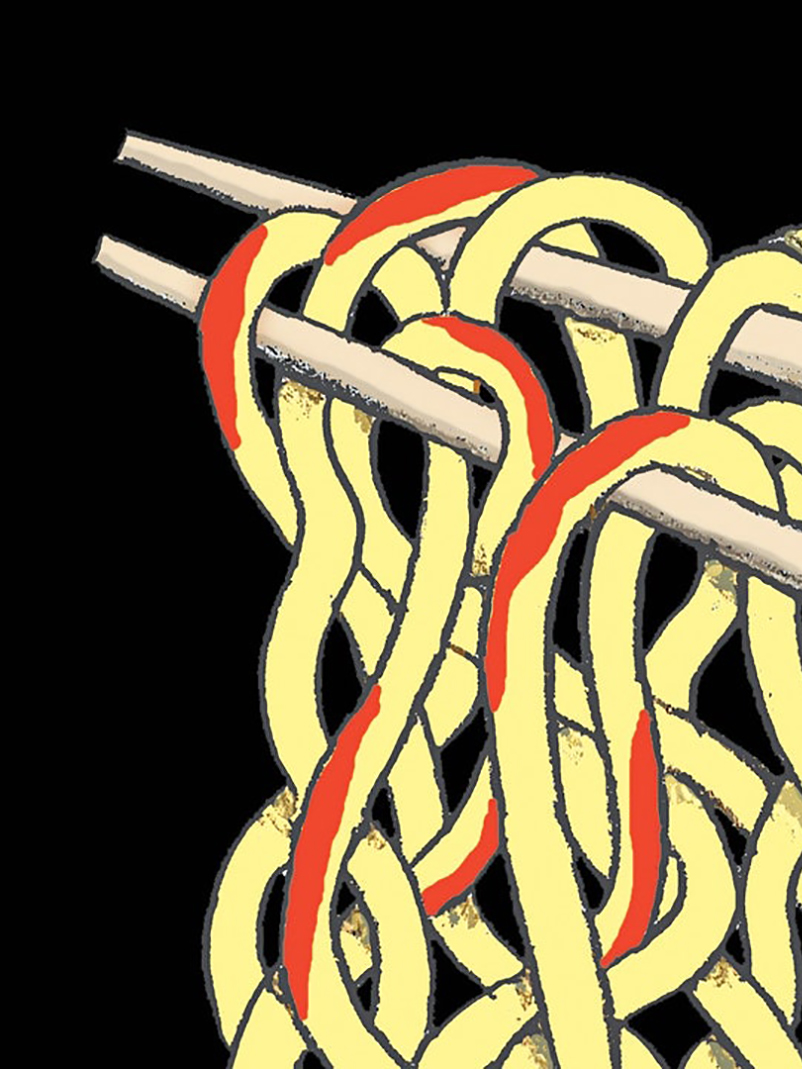

Nineteen seventy-one was the Year of Pasta.

In 1971, I cooked pasta to live, and lived to cook pasta. The steam rising from the pot was my pride and joy, and the bubbling tomato sauce in the pot gave me great hope in life.

I went to a cookware store and bought a kitchen timer and a huge aluminum pot, big enough for a German Shepherd to jump in and bathe in. Then I wandered through the expat supermarkets, stocking up on all sorts of spices with bizarre names. I picked up a spaghetti recipe book at the bookstore and bought a dozen tomatoes. I brought home every brand of pasta I could find, making every sauce imaginable. The mixture of onions, garlic, and olive oil swirled in the air, forming a light cloud that drifted through every corner of my tiny apartment, permeating the floors, ceilings, and walls, clinging to my clothes, books, vinyl records, tennis rackets, and stacks of old letters. It was a scent you could probably smell even from a Roman aqueduct.

This is the story of the Year of Pasta, 1971 AD.

As is my habit, I cook spaghetti and eat it alone. I believe that pasta is a dish best enjoyed by myself. Honestly, I can't really explain why, I just know that's the case.

I always eat pasta with tea and a simple salad of lettuce and cucumber. I make sure I don't leave anything out. I arrange everything neatly on the table and enjoy my meal leisurely, glancing at the newspaper as I eat. From Sunday to Saturday, Pasta Day follows Pasta Day. A new Sunday begins a new Pasta Week.

Every time I sit down to eat a plate of spaghetti—especially on a rainy afternoon—I always have the feeling that someone is about to knock on my door. Each time, I imagine a different person. Sometimes it's a stranger, sometimes it's someone I know. Once, I thought of the girl with the slender legs I used to date in high school, and another time I even imagined myself, from a few years ago, knocking on my door. Yet another time it was William Holden, hand in hand with Jennifer Jones.

William Holden?

However, none of these people actually dared to enter the room. They hesitated outside, without knocking, like fragmented memories, and then slipped away.

Spring, summer, and autumn, I cooked and cooked again, as if cooking spaghetti was an act of revenge. Like a lonely, betrayed girl throwing old love letters into the fireplace, I tossed handful after handful of spaghetti into the pot.

I gathered all the trampled shadows of time, molded them into the shape of a German Shepherd, threw them into a pot of boiling water, and sprinkled salt on them. Then I stood watching the pot, chopsticks in hand, until the stopwatch let out a mournful sound.

Those spaghetti noodles were a cunning bunch; I couldn't take my eyes off them. If I turned my back, they'd most likely slip off the edge of the pot and disappear into the night. The silent night was waiting for its chance to ambush the fleeing noodles.

Baked eggplant and cheese pasta

Napoli sauce pasta

Seafood pasta

Garlic oil-marinated spaghetti

Spaghetti with egg and bacon

Spaghetti with clams

And then there were those other anonymous, pathetic leftover portions of spaghetti, haphazardly thrown into the refrigerator.

Born from boiling water, the spaghetti strands floated down the river in 1971 and disappeared.

I mourn all of them - all of the 1971 spaghetti.

When the phone rang at 3:20 p.m., I was lying stretched out on my tatami mat, staring at the ceiling. A puddle of winter sunlight fell on me. I lay there like a dead fly, empty, in the December sun.

At first, I didn't recognize it as a phone ringing. It was like a strange piece of memory cautiously creeping into the air. But eventually, it took shape, becoming an unmistakable phone ring. One hundred percent a phone ringing in a real, one hundred percent real space. Still lying there, I reached out and picked up the receiver.

On the other end of the line was a girl, a girl so elusive that by four thirty she would probably have vanished completely. She was the ex-girlfriend of a friend of mine. Something had brought them together, this guy and this elusive girl, and something had also caused them to break up. I admit that I reluctantly played a role in their initial acquaintance.

"I'm sorry to bother you," she said, "but do you know where he is right now?"

I looked up at the phone, my eyes tracing the length of the wire. It was definitely still connected to the phone. I tried to give a vague answer. Her voice sounded unusual, and I knew I didn't want to get involved in any trouble, whatever it might be.

"Nobody's telling me where he is," she continued coldly. "Everyone's pretending they don't know. But there's something important I need to tell him, so do it—tell me where he is. I promise I won't drag you into this. Where is he?"

"Honestly, I don't know," I replied, "It's been a long time since I've seen him." It sounded so different from my own voice. I had told the truth about not having seen him in a while, but the rest wasn't true—I did know his address and phone number. My voice always sounds strange when I lie.

She didn't respond.

The phone was ice-cold.

Then everything around me turned into icebergs, as if I were in a science fiction story by J.G. Ballard.

"I really don't know," I repeated, "He left a long time ago, without saying a word."

The girl laughed. "Oh, come on. He's not that smart. We're talking about a guy who makes a lot of noise doing everything."

She's right. My friend is a bit silly.

But I wasn't going to tell her where the guy was. If I did, he'd just call me complaining about everything. I didn't want to get involved in other people's troubles anymore. I'd already dug a hole in the backyard and buried everything that needed to be buried. No one could ever dig it up again.

"I'm sorry," I said.

"You don't like me, do you?" she suddenly said.

I don't know how to answer that. It's not that I don't like her. I just don't have any real impression of her. How can you have a bad impression of someone who doesn't make any impression on you?

"I'm sorry," I repeated, "but I'm cooking spaghetti right now."

"What?"

"I said I was cooking pasta"—I lied. I don't know why I said it. But that lie had become a part of me—to the point that, in that moment, it didn't seem like a lie at all.

I filled an imaginary pot with water, and lit an imaginary stove with an imaginary match.

"So what?" she asked.

I sprinkle imaginary salt into boiling water, gently drop a handful of imaginary spaghetti into the imaginary pot, and set eight minutes for the imaginary kitchen clock.

"Then I can't talk. The pasta will be ruined."

She didn't say anything.

"I'm really sorry, but cooking pasta requires concentration."

The girl remained silent. The phone in my hand started freezing again.

"Could you call me back later?" I quickly added.

"Because you're busy making spaghetti?" she asked.

"YES".

"Who are you cooking for, or are you eating alone?"

"I'm eating alone," I replied.

She was silent for a long time, then slowly exhaled. "You don't know, but I'm really struggling. I don't know what to do anymore."

"I'm sorry, I can't help," I said.

"It involves money as well."

"I get it".

"He owes me money," she said, "I lent him some. I shouldn't have, but I had no other choice."

I was silent for a minute, my mind drifting to the pasta. "I'm sorry," I said, "But I'm still cooking the pasta, so..."

She gave a weary smile. "Goodbye," she said, "Please send my regards to the pasta. I hope it's okay."

"Goodbye," I replied.

When I hung up, the patch of sunlight on the floor had shifted a few centimeters. I lay back down in that pool of light and continued to stare at the ceiling.

Thinking about a pot of spaghetti that just keeps simmering but never cooks properly is really, really sad.

Now I regret not saying anything to her. Maybe I should have revealed something. I mean, her ex-boyfriend wasn't anything special either – an artistic fool with an empty shell, a smooth talker nobody trusted. It sounds like she's short on money, and, whatever happens, she has to pay back whatever she borrowed.

Sometimes I wonder what happened to her—that thought often crosses my mind when I sit in front of a steaming plate of spaghetti. After hanging up, did she disappear forever, vanishing into the shadows of 4:30 p.m.? And am I partly to blame?

But please understand my situation. At that time, I didn't want to get involved with anyone. That's why I kept cooking noodles, all alone. In a huge pot, big enough for a German Shepherd to jump in and bathe in.

Wheat stalks sway in the breeze across the Italian fields.

Can you imagine how astonished the Italians would be if they knew that what they exported in 1971 was actually...loneliness?

Additional information

In a 2002 interview with Haruki Murakami, his characters in this book were described as people searching for a way to understand life, with realistic imagery that is somewhat incomprehensible. Murakami explores the disorder, isolation, and loneliness that a person's perception of reality can create.

The concept of "super-realism," proposed by the French theorist Jean Baudrillard, describes "something" where reality and illusion are completely intertwined, with no clear separation, and people find themselves in harmony with the illusion and further from reality.

"In the short story 'The Year of Spaghetti,' the act of cooking spaghetti represents how the character's consciousness receives information from reality (buying spaghetti), interprets it psychologically (cooking spaghetti), and connects it to his own opulent reality (eating spaghetti). The final result (cooked spaghetti) is seen as an act of self-narration" - According to Jordan Eash.

*This translation is from *The Year With Spaghetti* - the 14th short story in Haruki Murakami's collection *Blind Willow • Sleeping Woman*, translated into English by Philip Gabriel.

VI

VI EN

EN