Text and photos:Nguyen Chi Linh

My friend Karen, an English teacher, and I decided to book a Jeep tour from the capital Ulaanbaatar to experience the nomadic life of the ancient Mongolians. Our guide was Gana, and our driver was Burmaa. Gana spent about an hour shopping for groceries at the supermarket to prepare for the trip.

The fascinating "Grand Caynons" in the ancient desert.

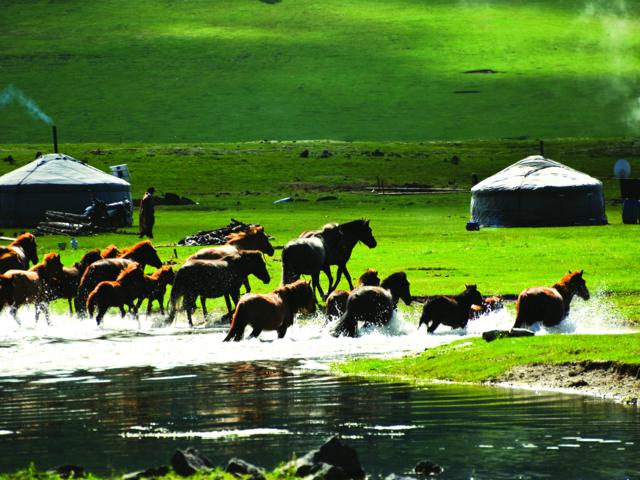

Gana kept asking us if we knew anything about Genghis Khan. To her and the Mongolians, he was a great hero and the father of the nation. All banknotes bore his image as a tribute. Gana explained that the Gobi Desert nurtured the land where Genghis Khan's majestic horses galloped across different regions on their conquest of Asia and Europe.

The Gobi Desert is one of the five largest deserts in the world and the largest in Asia. Stretching approximately 800km from north to south and 1,600km from southwest to northeast, the Gobi is one of the coldest deserts in the world. In winter, the desert is often covered in thick, mystical fog, and the mountain peaks are usually blanketed in white snow. Temperatures can sometimes drop to as low as -30 degrees Celsius. In summer, the climate is warmer. What makes the Gobi particularly different from other deserts is that temperatures can change rapidly within a single day, creating multiple distinct seasons, according to Gana.

The sky was cloudless, like a giant blue silk cloth draped across the land, the sun shining brightly, bringing warm rays that lessened the chill from the desert winds. We stopped in Erdenedalai after a day of traveling from the capital Ulaanbaatar. Erdenedalai is a city located in southern Mongolia and is the gateway to the Gobi Desert. It is a land where vast grasslands blend with the desolate desert. Gana took us to see the rocks that have emerged from the desert and are cut into various shapes, especially those shaped like eggs.

I gazed at the protruding rocks and silently likened those sandstone formations to children born from poverty, for they weren't as beautiful or famous as Cappadocia in Türkiye or the Grand Canyon in the United States. But no, it was still beautiful, and beautiful in a simple, honest way, typical of the Mongolian people. It still sang its songs day after day with the sweet meadows surrounding it, and on those meadows still echoed the hooves of the great Genghis Khan on his conquests.

It is said that stones are inanimate objects, without souls. But no, in the Gobi Desert, they suddenly become imbued with souls through the interplay of light and shadow.

Volcanic activity not only provides humans with a large amount of fertile basalt soil for farming and cultivation, but also leaves behind fascinating natural landscapes. The term "hoodoo" is often used to describe the oddly shaped rocks formed by volcanic activity in deserts or hot, dry regions.

"Hoodoos" are typically tall rock formations, varying in height from about head height to the height of a 10-story building. They often feature thin, spiral grooves at the top. The summits of "hoodoos" are usually composed of hard sedimentary rock that is less susceptible to erosion, allowing them to remain stable over time.

Geological studies have also shown that typical "hoodoos" are composed of a thick layer of volcanic rock (this rock layer is formed by volcanic ash binding together); outside this rock layer is a thin layer of basalt soil or other volcanic dust. This outer layer of red basalt soil or dust helps to protect the "hoodoo" from erosion over time and other factors such as rain, wind, sunlight, and temperature. Because they are formed by volcanic activity, "hoodoos" contain many minerals. These minerals give "hoodoos" many different colors depending on the sunlight, and this color varies greatly depending on the altitude of the "hoodoo".

The following days, Gana took us deep into the desert in the Tsagaansuvarga, Bagagazariinchuluu, and Bayanzag regions, where the "hoodoos" were formed. Both Karen and I were fascinated by the sight and the wanderings around these "hoodoos" in their various shapes: young bamboo shoots, mushrooms, chimneys of fairytale castles, or seated figures… They displayed different colors in the twilight and at dawn. My fascination was so intense that I forgot about the cold winds that suddenly swept across the steep cliffs at sunset and sunrise.

Then, high up in those mountains, a few small wells were formed inside the rocks. Gana called it Holy Water and scooped some for us to try. According to the local belief, drinking or washing one's eyes with Holy Water helps people live longer and have a clearer mind.

Experience life in the desert wilderness.

The Burmaa driver smoothly steered the car through the vast desert. What puzzled Karen and I was how he could navigate so easily, despite the complete lack of road signs amidst the desolate grasslands and sand dunes. Burmaa explained that those who have lived in the desert for a long time navigate by the sun and stars. He, however, found his way by observing the shapes of the mountains and the stone temples of the Mongolian people perched on the mountaintops. Simply by seeing and following these stone temples, he knew a village or town was nearby.

We spent the night in traditional Mongolian yurts. The white yurts looked simple from the outside, but were colorful and quite beautiful inside. Most activities, including meals, took place in the main yurt of the host family; the other yurts were for overnight guests. Inside, the yurt was divided into two sections: the left side contained a bed and a small table for the male head of the household, while the right side contained a bed and a kitchen for the female head of the household. Connecting the two sections was an ancestral altar and religious shrine. In front of the altar was a small table for communal activities such as meals or tea. A large stove with a chimney was located near the entrance, used for daily cooking and also serving as a heater in winter.

Every afternoon, if we weren't reading, Karen and I would join our host family in shearing camels and sheep. Uncle Bataar, our host in the Tsagaansuvarga region, shared that water and electricity are two crucial elements, almost the entire source of life for the self-sufficient lifestyle in the desert. The traditional occupation of the locals is livestock farming on the vast grasslands. Once groundwater is found, the nomadic lifestyle becomes settled.

Bundles of camel hair were braided and stuffed into felt sheets to create the domes or surrounding walls of the yurt. Sheep wool was woven into warmer sweaters for winter, and animal dung was collected and dried to use as fuel for cooking and as a heating agent when the weather changed. Horses and camels transported water from underground springs to the yurt for storage. Wealthier families bought batteries to watch television or light lamps for evening tea and conversation. Telephones were hung precariously from the yurt's dome to receive a signal.

I also learned the Mongolian method of washing dishes incredibly efficiently by using many towels after each rinse. Karen, who had more experience venturing into the desert than I did, brought along many useful items for the lack of water: wet wipes for wiping her face every morning, mouthwash made into a gel-like consistency, and candles for reading at night. Living in such deprived conditions, I still felt happy because, more importantly, I gained valuable experiences of the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongolians.

The happy days eventually passed. Living in conditions lacking many things, I still felt happy because, more importantly, I had the experience of the nomadic life of the Mongols. And I think that it was this lifestyle that enabled Genghis Khan's cavalry to navigate the situation on their conquest of Asia and Europe in ancient times.

Additional information:

+ There are two airlines operating flights from Ho Chi Minh City or Hanoi to Ulaanbaatar: Air China and Korean Air. Korean Air is a better choice because the layover time is only 12 hours compared to Air China's 22 hours.

The weather in Ulaanbaatar is very harsh and changes suddenly; a single day can feel like several seasons, so it's necessary to check the status of flights before departure.

Most tourists have to buy a tour to enter the Gobi Desert. Tour prices depend on the number of participants, ranging from 50 USD to 80 USD per person per day.

The currency of Mongolia is the Tughrik (MNT). You can exchange money at local banks at an exchange rate of 1 USD = 1.825 MNT.

Ulaanbaatar, the capital city, is not very large, and the attractions are quite close together, allowing visitors to easily walk to see: Ganda Pagoda, Sukhbaatar Square, Zanabazar Art Museum, the International Museum, Bogd Kahn Summer Palace, etc.

VI

VI EN

EN