Walking through Paris in the morning, the first thing you see is the stream of people leaving local bakeries to buy breakfast pastries. That's because, throughout France, getting up early and buying a baguette isn't just second nature; it's a way of life. According to the Observatoire du Pain (yes, France has a scientific organization called "The Bread Observatory"), the French consume 320 baguettes every second – that's an average of 1/2 baguette per person per day and 10 billion baguettes per year.

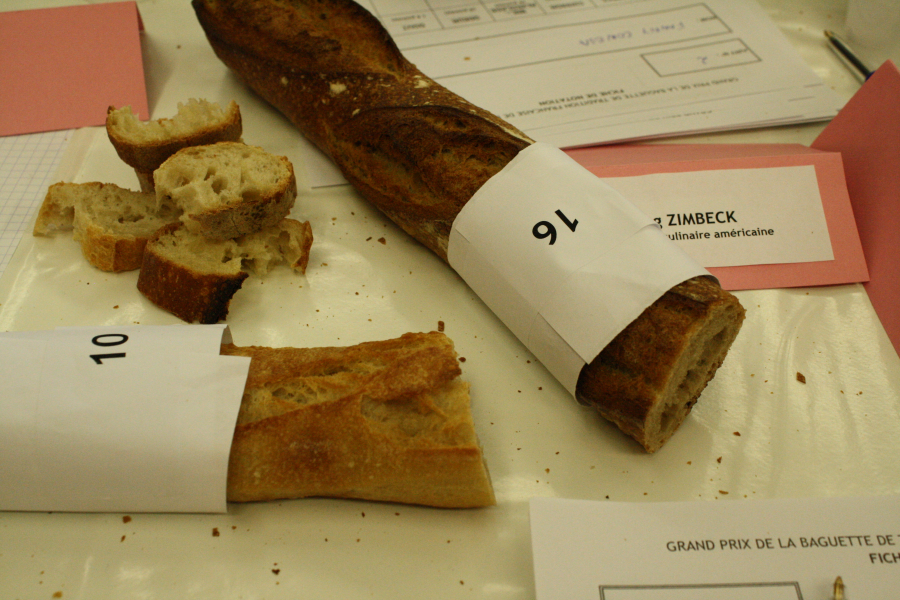

So, it's no surprise that France places great importance on baguettes. In fact, every April since 1994, a jury of experts gathers in Paris to judge Le Grand Prix de la Baguette: a competition to determine the best baguette maker in the city.

Each year, around 200 bakers participate in Paris's most coveted pastry competition: Le Grand Prix de la Baguette.

Each year, around 200 Parisian bakers participate in a competition, submitting the two best baguettes to a panel of expert judges in the morning. The baguettes are inspected to ensure they are between 55-65 cm long and weigh between 250-300 g. Nearly half of the more than 400 baguettes submitted meet these stringent criteria and advance to the second round: evaluation.

In the next round, a panel of 14 judges—including food journalists, the previous year's winner, and a few lucky volunteers—will analyze the remaining loaves based on five different criteria: baking consistency, appearance, aroma, taste, and texture. The texture of a baguette should be soft but not moist; elastic, with large, uneven pores, indicating that it has fermented slowly and developed its aroma.

Last year's champion, Taieb Sahal, of Tunisian origin, was the youngest winner ever, at age 26. Prior to that, in 2018, another Tunisian, Mahmoud M'seddi, also won Le Grand Prix de la Baguette at the age of 27.

"I was fortunate enough to grow up in a bakery," M'seddi shared, standing beside the irregularly shaped, handcrafted loaves of bread at his small M'seddi Moulins des Prés bakery in the 13th arrondissement. "I grew up with my parents, unlike children who were cared for in nurseries or had nannies. I was always in the bakery."

M'seddi's passion for baking is evident and stems from his father. Originally from Tunisia, M'seddi's father came to France in the late 1980s to pursue a degree in electrical engineering. "During a school holiday, he went to Paris to work at a bakery to earn some pocket money and fell in love with baking. He dropped out of school. Instead, he started baking," M'seddi recounts.

M'seddi fondly remembers watching his father mold dough into baton-shaped baguettes and working alongside him as a child. "Like a magician," he recalls. "I did that when I was little, mixing things together. I loved doing it."

When he won in 2018, Mahmoud M'Seddi was only 27 years old.

Despite his mother's warnings against becoming a professional baker due to the demanding nature of the work and the lack of holidays, M'seddi decided to join the family business. M'seddi and his father now run three bakeries in Paris: Boulangerie M'seddi Moulin des Près, located south of the picturesque Butte aux Cailles district; Boulangerie Maison M'seddi Tolbiac, a few hundred meters away; and Boulangerie Maison M'seddi in the 14th arrondissement.

Every morning, M'seddi wakes up at 4 a.m. to begin preparing the dough for his now-famous, entirely handmade bread. Plump in shape and light brown on the outside, it's a prime example of what a true Parisian baguette should look like.

But he kept his secret to making the perfect baguette a secret.

"I won't say," M'seddi replied with a forced smile.

According to Sami Bouattour, the 2017 winner, baguette perfection is as elusive as M'seddi's performance. "When I was on the judging panel," Bouattour said, "it was easy to pick out the 10 or 20 best baguettes. But then, when you compare a number 3 and an number 8, the difference is very small."

For M'seddi, the magic that makes his baguette stand out from the billions of others consumed in France each year is simple: passion. "You can have exactly the same recipe," he says. "And if one person is more passionate than another, they'll get a better result. Even if you do it exactly the same way, it's not the same. It's like magic."

M'seddi's Bakery

M'seddi was granted the right to display a large gold decal on the window of his bakery to advertise his status as a baguette champion. But that wasn't all. The winner each year also had the honor of supplying bread daily to the French president – a privilege M'seddi proudly shared with the public through social media videos of his early morning routine of carrying a basket of fresh baguettes to the sprawling Elysée Palace.

Emmanuel Macron is clearly passionate about France's bread-making heritage: in 2018, the president proposed that the French baguette be recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Neapolitan pizza, Croatian gingerbread, and flatbreads from Central Asia have all appeared on UNESCO's list. But according to Macron, "the baguette is a coveted item worldwide."

The baguette is not just a staple – it's a symbol of French character.

But while few symbols embody the quintessential French character of the baguette, its status and quality have been inconsistent in recent years. Beginning in the 1950s, bakers began finding shortcuts to make baguettes faster: relying on pre-made and frozen dough; and baking baguettes in molds rather than free-form. Instead of the crispy-on-the-outside, soft-on-the-inside loaves that M'seddi baked each morning, these soggy, pale baguettes would lose their flavor as quickly as they cooled. By the 1990s, they had become the norm for bakers and for Parisians.

"The bakers were so happy back then," Bouattour said as he led me through the freshly baked loaves at his Arlette & Colette shop in the 17th arrondissement of Paris. "But it killed our profession." At Arlette & Colette, Bouattour sells a range of breads, pastries, and viennoiseries, all handmade and all using certified organic ingredients.

French President Emmanuel Macron recently declared that baguettes are a global delicacy.

In an effort to save the traditional French baguette from widespread industrialization, France passed the Bread Decree in 1993, which mandated that a truly traditional baguette must be handmade, sold in bakeries, and made only with water, flour, yeast, and salt. Today, these new "traditional baguettes" account for about half of all baguettes sold in major French cities – and are the subject of a competition held annually since 1994.

However, nowadays, some argue that supermarket bread, which is much cheaper than loaves sold in bakeries, is driving artisans out of the market. After all, French radioEurope 1Reports indicate that 1,200 small bakeries in France close down annually.

"It's a shame," M'seddi said. "It's bread. It's French. You need to buy it at a bakery, where people get up early, where they bake by hand."

The Bread Decree of 1993 stipulates by law that a truly traditional baguette must be handmade, sold in bakeries, and made only with water, flour, yeast, and salt.

In addition to winning this prestigious competition, Bouattour and M'seddi share several other things in common. Both have completed the traditional trade school that many French bakers aspire to enter at age 16. Both have been professional bakers for less than a decade (as has the 2019 winner, former engineer Fabrice Leroy). And both are first-generation French, what Bouattour euphemistically calls "of French descent": their family origins are elsewhere – or, in their case, Tunisia.

Recalling racial origins is taboo in France, in the name of equality. The government has not collected information on the race or religion of its citizens since the 1970s (a policy largely stemming from surveys conducted during the Nazi occupation of France). But while France's official political stance is to create equality, the fact that beaches ban burkinis (the modest swimsuit worn by Muslim women) and the naturalization office suggests Frenchifying the names of new citizens seems to say something to those of "French descent": assimilate.

The Le Grand Prix de la Baguette competition created a level playing field as all baguettes were numbered.

However, the Le Grand Prix de la Baguette competition does a pretty good job of creating a level playing field for bakers, regardless of their knowledge and experience.

"All the baguettes are numbered, so we don't know who we're reviewing," said Meg Zimbeck, founder of the restaurant review website.Paris by Mouth"The only difficulty was that our taste buds got tired. We had to taste so much," she explained, describing her experience as a judge.

Traditional baguettes are the specimens judged in the competition held annually since 1994.

Notably, since 2015, four winners have been French bakers of African descent.

Djibril Bodian is the baker at the bakery.Le Grenier à PainIn picturesque Montmartre, Bodian, the son of a baker and a first-generation Frenchman of Senegalese descent, decided at age 16 to follow in his father's footsteps. Almost immediately, his pastry school teachers recognized his natural aptitude for the craft.

"The teachers started treating me like a role model, telling others, 'Do it like Djibril!'" he recounted. "That gave me recognition, but it also put pressure on me. I didn't want to disappoint my teachers."

Baker Djibril Bodian has won the Paris Grand Prix twice, in 2010 and 2015.

According to the rules, the winner of Le Grand Prix de la Baguette is not allowed to compete for four years afterward. But after winning the title of best baguette in Paris in 2010, Bodian said, "I only had one wish: to compete again as soon as possible. So, for four years, while people might think I was resting on my laurels, I was working, trying to do better."

In 2015, Bodian won the competition for the second time.

"It's a great pleasure and an honor," he said, smiling. "But when I became a baker 22 years ago, nobody thought a baguette could get you to the Elysée Palace."

Bodian's success is due to both his background in the Senegalese environment and values, as well as his training in France.

"I stopped thinking of myself as a foreigner a long time ago, but my origins have made me the person I am today," he said. "We all start with the same tools, the same teachers, but some people begin to understand things differently. It has nothing to do with origin; it's just talent."

The stories of Bodian, Bouattour, M'seddi, and Sahal resonate with a reminder of France today: a diverse and multicultural country of people who are proud to be French.

"Whoever wins the competition is the winner," M'seddi said. "That person is the champion, whether they are an immigrant or not."

What could be better than pinching off a piece of baguette?

And while he dismissed the importance of evoking a foreign ancestry, he acknowledged that there was a certain element of pride when someone of foreign descent won the top prize.

"He was someone passionate about French culture, someone who had become integrated as a Frenchman," he said. "We need to make people feel proud to be French."

What better way to feel proud than by taking a bite of a baguette?

VI

VI EN

EN