Technically speaking, Molise does exist. As one of Italy's 20 official regions, Molise holds the same status as Tuscany, Lombardy, or Piedmont. It hosts regional and national elections. It borders Abruzzo, Puglia, Lazio, and Campania, all of which are real, existing territories—no one can dispute that.

So why do Italians like to pretend that Molise didn't exist?

"I first came across this on the internet a few years ago," said Enzo Luongo, a journalist and author of Il Molise Non Esiste (Molise Does Not Exist).

"People started posting the hashtag #ilmolisenonesiste as a joke, mocking the fact that this place is so small and our relative vulnerability in Italy."

However, what surprised Luo was the creativity of the comments inspired by this hashtag, ranging from amused reactions ("I put 'Molise Doesn't Exist' as my Facebook status. My geography teacher liked it.") to those dismissing it as silly ("I met a guy from Molise who was doing an Erasmus program in Italy." - Erasmus is a program that doesn't operate in Italy).

It seems that this region, previously overlooked, has suddenly awakened the latent creativity within the Italian people.

The "Molise conspiracy" has become a cultural phenomenon in Italy, manifested in books, songs, videos, stage monologues, news, and many other forms. It has been talked about by everyone from comedian Capppe Grillo to former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. A popular Facebook page called Molis't - lo non credo nell'esistenza del Molise (Molisn't - I Don't Believe in Molise's Existence) sells merchandise printed with the word "Molisn't," such as t-shirts and drinking mugs.

Fake scientific papers were published, speculating about the existence of this region, while memes appeared on the internet comparing Molise to Narnia (a fictional land) and depicting maps of Italy with a black hole representing the region's location.

A video posted on YouTube in 2015 – titled IL MOLISE NON ESISTE! – has garnered over 1.6 million views, more than five times the total population of Molise, which is 305,000 people.

In just a few years, Molise went from being an obscure figure to a national comedy in Italy.

Throughout Italian history, Molise has always been in a peripheral position.

In ancient times, this area was home to the Samnites, a mysterious tribe that clashed repeatedly with the Romans until they were subdued in the 3rd century BC.

Being a barren, mountainous region, this land was largely overlooked by the Romans, and again by the Oliver, Norman, Bourbon, and other conquerors.

As a periphery of the new Kingdom of Italy in 1861, it became part of the Abruzzo e Molise region created after World War II, but separated from Abruzzo in 1963 to become Italy's youngest – and least known – region.

The reasons for Molise's separation from Abruzzo are quite complex, and many residents would argue that it was perhaps a mistake and that they should have rejoined Abruzzo, where they have very strong cultural ties.

Currently, Molise focuses on developing slow tourism – scattered hotels, culinary tours, farm stays, and cultural tours.

They are trying to attract people who have already visited Rome, Venice, Florence... and are looking for something completely off the tourist map. In a way, Molise is the ultimate undiscovered destination in Italy.

The people of Molise viewed the phenomenon of "Molise Does Not Exist" as an opportunity to give the region a unique brand.

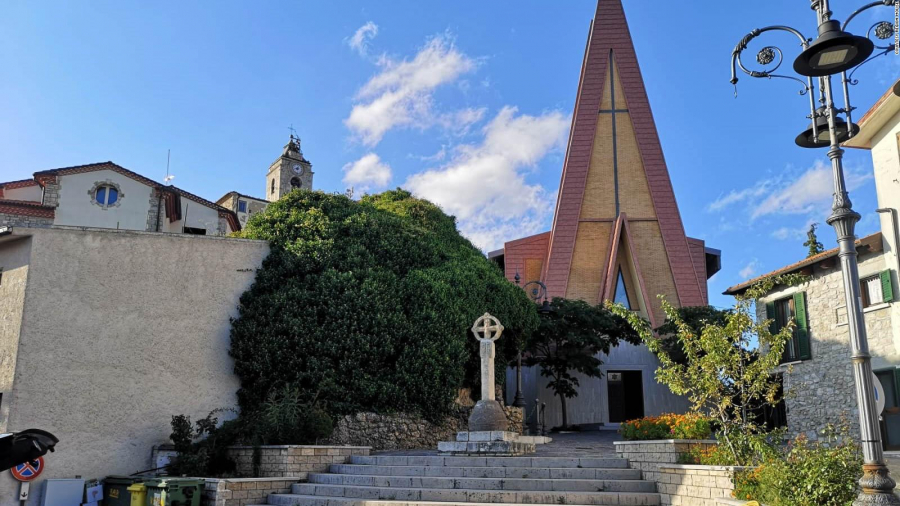

Climbing higher into the heart of the Molise region, the green hills give way to towering mountains, and scattered villages with their pencil-thin bell towers and closely packed houses seem to fade into the distance at the edge of the mountains.

Many villages in the area are still connected by tratturi – ancient sheep herding paths that are gradually being rediscovered as hiking trails.

One such village is Agnone, the home of Marinelli Bell Foundry.

Founded in 1339, it is the world's oldest continuously operating bell foundry, as well as Italy's oldest family business and the official supplier of bells to the Vatican.

Marinelli has become a symbol of the Molière spirit: life is not disrupted by tourism, so here, traditional customs play a paramount role.

"Molise is one of the last truly authentic villages in Italy. In fact, I would say it's a truly timeless place," said Simone Cretella, a local politician.

"Unfortunately, the government never believed we could attract tourists. They thought the only way to improve our development was through industry, so they built all the factories here," he added.

"Now the factories are closing and all the young people are leaving again."

In a region with a history of struggling with poverty, isolation, and earthquakes, the problem of decline is ever-present—and so pronounced that the region's president is offering to pay people to move to Molise.

Private investment in the region remains low, infrastructure is poor, and unemployment is high, forcing many young people to leave to find work elsewhere.

For some, "Molise Doesn't Exist" isn't a humorous joke, but rather a serious prediction about the region's future.

"Nobody wants to leave Molise. We have so much beauty and culture here. I feel very proud to live in a place where everything is beautiful," Cretella said.

"What we need is tourism. We need to offer services that encourage visitors to stay on farms, we need hiking trails, bike paths. We need young people to stay and develop the area through sustainable tourism. I feel this type of tourism can really save Molise."

Like many other Molise residents, Cretella sees "Molise Does Not Exist" as an unprecedented opportunity to promote the region both domestically and internationally.

"In other words, 'Molise Doesn't Exist' is a perfect brand," he said. "It showcases our strengths: our mystery, our enigma, and the fact that it's a place untouched by tourism. It creates curiosity that makes people want to explore, and when they do, they're always surprised to see how beautiful and diverse Molise is. No one is disappointed when they come to Molise. We just need to get that message across."

Cretella spent much of his political career trying to convince tourism authorities to adopt a marketing strategy based on the very idea that this place was supposed to be nonexistent, but he had little success.

One of the downsides of living in a "timeless" area, he explained, is that it's very difficult to change other people's mindsets.

Nevertheless, Cretella still believes that tourism is the future of Molise, and the idea that the place is a non-existent place will be at its heart.

"After all," he said, "who wouldn't want to visit a place that doesn't exist?"

VI

VI EN

EN