In Japanese, "Wabi" means asymmetrical and unbalanced beauty, while "Sabi" describes the beauty that is impermanent and enduring over time. Derived from the three fundamental aspects of existence in Buddhism—impermanence, suffering, and non-self—Wabi-Sabi is a philosophy of life that focuses on imperfections not to judge them, but to discover and celebrate their inherent positive qualities. This philosophy helps people view things simply, accepting their impermanent nature, thus making life easier and lighter.

While the West constantly strives for perfection, Japan values the beauty of fleeting moments, not needing to be overly flawless, simply encapsulated in the term Wabi Sabi. For the Japanese, Wabi Sabi is as important as feng shui is to the Chinese. More than just the soul of the tea ceremony, Wabi Sabi is also the aesthetic standard for many fields such as architecture, painting, poetry, and Japanese ceramics.

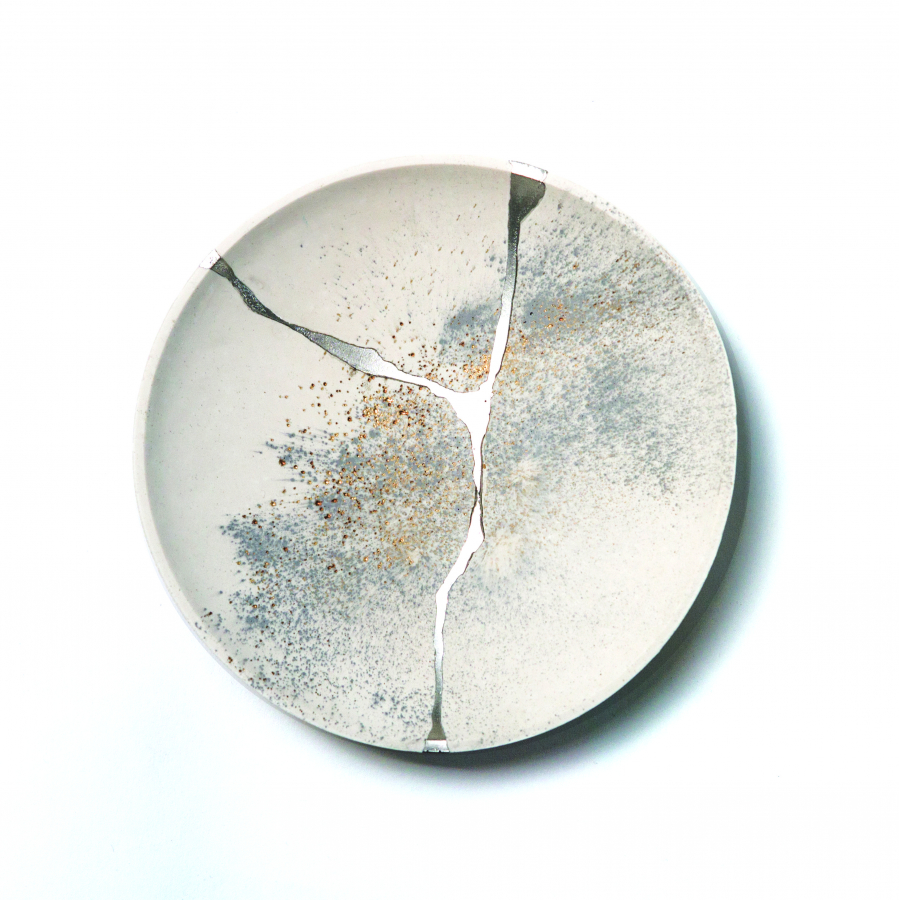

Kintsugi Art

Instead of discarding chipped or broken pottery, the Japanese have a way of "restoring" these items by joining them with gold leaf, a technique known as Kintsugi.

Kintsugi, meaning "Golden Wood," is a sophisticated restoration technique that symbolizes the humble and resilient Japanese way of life. Kintsugi artists use gold threads to repair damaged items. Broken pieces are collected and glued together using a secret adhesive mixture of gold, silver, or platinum. Beyond restoring the original condition of the dishes, the kintsugi process celebrates the cracks, transforming them into symbols of eternity, of rebirth after shattering, and into a precious beauty of uniqueness and imperfection. Each bowl bears different cracks; no two are alike. After kintsugi, these cracks become traces of history. Broken objects, seemingly destined for the end, are transformed into gold, marking the beginning of a story.

A Wabi Sabi item is considered beautiful when it is older, more rustic, more worn, and more personal.

Wabi Sabi and the tea ceremony

In 1199, the Japanese monk Eisai returned from China with the intention of establishing the first Zen Buddhist temple in his country. Upon his return, Eisai brought back a bag of green tea and introduced people to the method of brewing tea – considered the earliest style of tea ceremony in Japan, known as "Tencha." Later, this type of tea was used in religious ceremonies in Buddhist monasteries, especially during meditation, when monks used it as a means of activating alertness. However, over time, the art of tea ceremony also came to be used on various occasions, such as gatherings of the upper class. Many nobles and wealthy merchants organized tea parties to showcase the expensive teas and utensils they imported from China.

In 1488 in Kyoto, the monk Murata Juko was deeply disturbed by this distortion and wanted to redefine the art of tea drinking. He compiled the document Kokoro no fumi (Letter from the Heart), which described a tea ceremony based on the philosophy of Wabi Sabi. Alongside a relaxed style of tea drinking, he encouraged the use of worn stoneware or enamelware crafted by Japanese artisans.

Through his efforts and passion, Murata Juko not only brought the "true tea ceremony" back to his homeland, but also spread it to all levels of society. This spirit is continued and preserved to this day through tea ceremony instruction programs at many major schools following the tradition of Sen no Rikyu – the "master of the tea ceremony." In these classes, Rikyu teaches and guides how to combine the Wabi Sabi style into a new form of tea ceremony. He focuses on simple utensils, teapots, and related elements. One notable new feature is the tea bowl, made in the design of Raku pottery – the embodiment of the Wabi Sabi spirit.

Wabi Sabi and Raku-yaki pottery

Raku, meaning "relaxed" or "gentle" in Japanese, is a type of ancient Japanese pottery dating back to the 1550s. Raku pottery is often used in traditional tea ceremonies. Raku-yaki pottery is made using traditional handcrafted methods, molded entirely by hand rather than using a potter's wheel.

Regarding tea bowls made in the spirit of Wabi Sabi, after the shaping process, the product undergoes a low-temperature firing process (around 1,000°C).oC) Within about 50 minutes, the product is abruptly removed from the kiln and placed in a container filled with combustible materials such as sawdust and dry leaves to allow it to cool quickly after the kiln is opened. This method results in pottery that is quickly shaped but lacks a glaze. To enhance the aesthetic appeal of the product, artisans may use techniques such as wax coating, crackle glaze, copper glaze, or matte black paint. In some cases, potters even attach horsehair to their products and put them back in the kiln to create irregular patterns on the pottery.

VI

VI EN

EN

(Copy).jpg.jpg)

(Copy).jpg.jpg)