Among the tribes living in the hills of present-day Nagaland, the Konyak were particularly fearsome.

The Konyak people are divided into many small groups, each separated from the others by their language and facial tattoos. Their only commonality is their practice of headhunting. The beheading of members of rival tribes is considered a ritual among Konyak men. For this reason, it is not surprising that the Konyak tribe is one of the most isolated in the region.

But things began to change when India (then a British colony) started exploiting tea leaves in the Assam region, indirectly bringing British missionaries into the area. In the 1870s, missionaries from England began establishing schools in Assam, and in the following decades, thousands converted to Christianity.

At that time, the Konyak people became even more isolated.

The Raj government (in the British-occupied zone of India at the time) completely banned headhunting in 1935. By the 1960s, the younger generation of Konyak grew up and began to integrate into modern life, and thus, the unique facial tattooing culture gradually faded away.

Concerned about the permanent disappearance of this cultural form, Phejin Konyak—the great-grandson of a Konyak tribal headhunter—traveled from village to village in Nagaland district, speaking with elderly members of the Konyak tribe and recording their stories, songs, poems, and folk tales for three years.

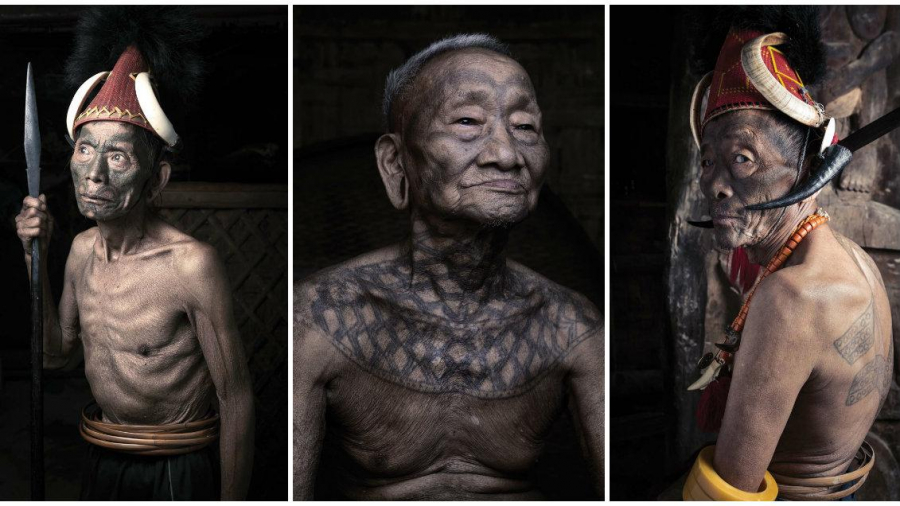

With the help of photographer Peter Bos, she also documented the unique tattoos on the faces and bodies of the Konyak people, each tattoo representing the tribe, clan, and social status of each member. In Konyak culture, life—headhunting—and tattoos are inextricably linked.

Leye Monyu, 68 years old

In the Konyak belief system, a person's skull is believed to contain all the spiritual energy of that being. This spiritual energy is strongly linked to prosperity and fertility, and is used for the benefit of the village, individual life, and crops.

But Phejin doesn't entirely blame foreign missionaries for the end of the tribal culture. In an interview with historian William Dalrymple, she confessed her mixed feelings about the missionaries' influence on the Konyak community, acknowledging that the school itself helped improve literacy rates in the area and opened a new chapter, a new future for the younger generation.

Phejin only wished that the missionaries had thought a little more deeply about their impact on the local culture. They taught that religion was the path to rebirth, and that if one wanted to be reborn, old habits should be discarded. In this way, they eradicated the culture of Phejin's ancestors.

Let's take a look back at this collection of photographs of the last remaining headhunters of the Konyak tribe:

Ashen Wenkhu-Hamyen, 98 years old.

Hensungaubu, 80 years old, smiles broadly, revealing his teeth traditionally dyed black.

Manchak Wankongpa, 80 years old, wears a hat decorated with two tusks of a wild boar.

Hangsha Salim, 78 years old

Binlei Wangnaolim, 85 years old

VI

VI EN

EN