A glimmer of hope

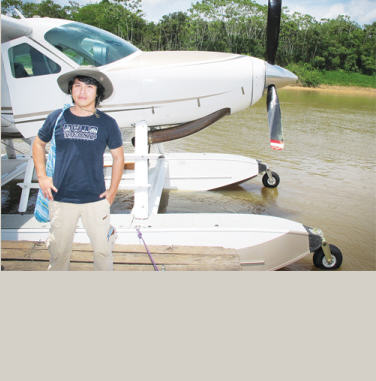

The author in Angamos before traveling by boat into Matsés territory - Photo: NT

Before going, I did a lot of research and read a lot of material about this region. The fascinating tribes I could encounter were the Shuar, the Jivaro (famous for shrinking their heads to the size of an orange), the Matis (known as the leopard people), and the Matsés (formerly warriors who abducted wives from other tribes). I spent an entire day asking dozens of travel companies and even the cultural department in Iquitos (Peru), but all I received were negative responses. "If you want to meet those tribes, perhaps only Amazon Explorer in Iquitos can guide you," said someone from the Amazon Indigenous Culture Research Society.

Amazon Explorer is a travel company in Iquitos with only two members: Hector (an Argentinian naturalist) and Bertien (a Dutchman who translates Spanish and English). They were quite surprised when I suggested they take me to meet "real" Amazonian natives. "2,400 USD for a 15-day trip," Hector said. This wasn't the time for bargaining, so I agreed. Hector held out a piece of paper: "Sign here." The paper was full of regulations and warnings, but it all boiled down to one sentence: "We are not responsible for any accidents." "Is there anywhere to buy insurance?" I asked. Hector laughed: "No company will sell insurance for customers going into the Amazon rainforest. And let me tell you beforehand, don't even think about helicopter rescues or anything like that from the movies. Once you're in the jungle, you accept all risks!"

Matsés territory

Angamos is considered the last remaining "civilized" place because it still uses electricity from batteries and has a few small grocery stores. Denis (29 years old) - a Matese guide who also translated from Matese to Spanish - met us in Angamos.

Today, Amazonian indigenous people receive more protection from the government. Entry into their territory requires a permit. A European explorer was once imprisoned in Brazil for falsely claiming to be a friend of the indigenous people in order to penetrate deep into their territory. Even if permits are obtained or authorities are deceived, there have been instances of indigenous people "welcoming" intruders with traps or poisoned arrows.

The Matsés region is a national reserve. Therefore, don't even think about exploring it on your own. "Once you enter the restricted area, anything can happen. If you don't go with the Matsés, the opium growers and smugglers are ready to kill strangers because they don't know if you're a tourist or a government agent sent to arrest you," Denis said.

The small boat, loaded with necessities—eggs, condensed milk, soap, dried food…—along with four people: myself, Hector, Bertien, and Denis, set sail down the Yavarí River. Pointing to the fork where the Yavarí and Gálvez rivers meet, Denis said, “We are entering the territory of the Matsés people.”

Unlike other rivers, the Gálvez River appears black due to chemicals released from the bark of the forest trees. These chemicals help filter the water, killing bacteria and mosquito larvae. As a result, the area where the Matsés live has few mosquitoes.

Along the Gálvez River are tall kapok trees with wide canopies. Perched densely on the treetops on both banks of the river are the symbols of Honduras (Central America): flocks of Amazonian parrots, long-tailed, brightly colored, and as big as chickens, squabbling noisily. "These parrots are very loyal, always flying in pairs, never alone," Hector revealed.

Occasionally, we would see pink dolphins (a type of freshwater dolphin characteristic of the Amazon region) leaping and playing in the water. According to the documents I read before the trip, the Matsés people are very afraid of pink dolphins because they believe they often disguise themselves as beautiful girls or boys to lure and drag people to the bottom of the river. Therefore, the Matsés do not eat pink dolphin meat because they believe its spirit will kill them. Just as I was verifying this information with Denis, a small boat rowing upstream towards Angamos came from the opposite direction, carrying a young boy whose entire body was swollen and who was almost delirious. “While bathing in the river, a pink dolphin swam very close to him. That’s why when he got ashore, he’s like this,” the boy’s father (also a Matsés man) told Denis in a voice full of fear.

The sun was scorching. It was the dry season, so the water was low, yet we were still sticky with sweat due to the high humidity. After eight hours sitting on the boat, my skin was burned red like a boiled shrimp. As the sun was about to set behind the old forest, and everyone was feeling faint from sunstroke and exhaustion, we caught a glimpse of small, bare-chested figures… Denis shouted, “We’ve arrived!”

From Iquitos, you can reach Angamos by seaplane, whereas a boat trip would take about a week. From there, you continue upstream by motorboat for another 8 hours to reach Buen Peru and San Juan (home to the Matsés people). Another option is a 19-hour boat trip from Iquitos to Requena (160 km), followed by a 3-day trek through the jungle. This route is slightly shorter but far more dangerous.

VI

VI EN

EN