On a gloomy day in London, England, in January 1349, the first bells rang out, warning of the Black Death pandemic. These bells plunged London into an atmosphere of fear and death for months. Londoners had been warned of God's plague harbinger sweeping through other European cities like Florence, where 60% of the population had died from the terrible disease a year earlier. But these warnings were not enough. Only when confronted directly with the Black Death did these mortals understand just how cold and terrifying the Grim Reaper's scythe truly was.

The "protective gear" worn by doctors during the Black Death (Photo: Internet)

Earlier, in the summer of 1348, the plague appeared in Europe and gradually spread to the center of the continent. The plague caused painful symptoms including fever, vomiting, coughing up blood, black pustules on the skin, swollen lymph nodes, and patients usually died within three days. When faced with the Black Death, all the London authorities could do was build the enormous East Smithfield cemetery to bury as many infected people as possible in land blessed by the church, so that God could identify the dead there as Christians on Judgment Day. Unable to save lives, the city of London could only try to save souls.

The plague did not disappear after the Black Death. Many countries, such as England and Italy, experienced successive outbreaks. In fact, the Black Death is just one prime example of how a pandemic lasting four years can profoundly change the face of the world and entire human civilization.

The chaos of European society during the plague (Painting: The Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel, 1562)

A test for humanity

The Black Death (or Bubonic Plague) refers to the plague epidemic that swept across the Eurasian continent in the mid-14th century. Famous throughout Europe as the Black Death, this disease is believed to have been caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread through fleas that lived on rats, which were transported along all the trade routes, both sea and land, at the time. The scale of this epidemic has evolved with the course of human history, associated with three major global outbreaks, including:

- The plague during Justinian's time (541)

- The Black Death (1348)

- Third wave of the epidemic (1855)

These examples illustrate the fragility of human socio-political structures, reflecting the consequences of globalization, war, trade, and imperial expansion, which have created networks through which not only silk but also rats and disease-causing agents (in this case, epidemics) have the opportunity to travel globally. At the peak of these epidemics, 800 people died in Paris (France) a day. The number was 500 in Pisa (Italy) and 600 in Vienna (Austria). Half the population of Siena (Italy) died within a year. Similarly, Florence (Italy) lost 50,000 out of a population of 100,000.

Not only silk, but also rats and the seeds of disaster/disease have the opportunity to travel globally. (Painting: Two Rats, Vincent van Gogh)

Other statistics indicate that around 50% of the world's population has fallen victim to plague, and this number could be as high as 75-100 million people. The last major plague outbreak was in 1855, starting in China, and killed 10 million people in India alone. It wasn't until 1895 that Dr. Alexandre Yersin discovered the cause of the plague while studying its outbreak in Hong Kong.

History shows that while disease itself is catastrophic, human overreactions are the catalysts that create chaos and death on a far greater scale. Each time a pandemic has appeared in human history, it has served as a complete test of humanity's resilience in preserving the fragile survival of the species.

Hospital during an epidemic (Painting: Hospital Plague, Francisco de Goya)

These "prophecies" come from the past.

Despite the devastating consequences of the pandemic, there's a fact that few of us notice: throughout human history, pandemics have occurred as frequently as wars. In fact, a French existentialist philosopher wrote a story that, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, has become strangely relatable.

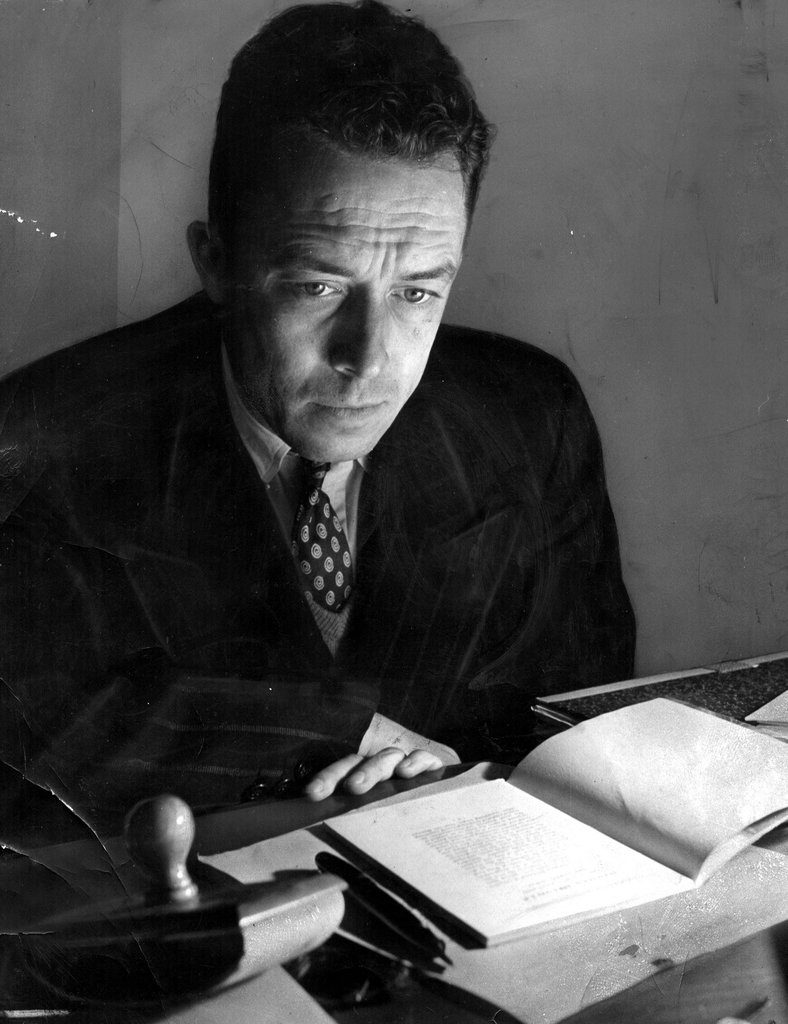

"The Plague"Albert Camus's *The Plague*, set in 2020 and 2021, can be read more as a narrative than a book. This is because the people of Oran experience a wide range of emotions. From the initial denial of the disease's existence, to the government's slow response, the shortage of crucial medical supplies, and the overwhelming strain on hospitals… Camus seems to have seen it all with uncanny clarity. Furthermore, Camus demonstrates an understanding that a pandemic can harm not only the physical but also the mental well-being of those caught in its path.

French writer, journalist, and philosopher Albert Camus (1913-1960)

One of the worst characteristics of the plague is that it seems to never end. A night watchman in “The Plague,” in a moment of panic, wished the city had been hit by an earthquake instead of the plague. He said:

“Earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and other similar natural disasters—as terrible as epidemics—all have one saving grace: they end quickly. They have a clearly defined conclusion, from which survivors can grieve and move on.”

On the other hand, each passing day of the pandemic brought a steady trickle of new deaths. The pandemic also caused another kind of loss: prolonged separation from loved ones as lockdowns took effect. Fears that the pandemic could last a year or even longer caused emotional disconnection and created uncertainty about when they would be reunited with family. Because of this, people in the epicenter of the pandemic often became disillusioned with a better future and decided it would be easier to stop thinking about it. Camus describes this situation as when people become like..."Wandering shadows" "drifting through life rather than living"tormented by"undefined memories".

The plague also robbed life of its simple pleasures. Not only were the inhabitants of the fictional town of Oran (in "The Plague") forbidden from moving around, they couldn't even stroll on the nearby beach. To put it clearly, Camus argues that the misfortune of the plague stemmed in part from its absolute monotony. Even the simplest pleasures were eliminated: an old man who used to enjoy spitting on stray cats on the street could no longer do so (for fear that they might be a source of disease). Camus wrote:"The pandemic has killed all the colors, negated all the joy."So, is there a way for people to overcome the negative feelings that despair brings?

Camus suggested that it exists.

Camus distinguishes between despair and "the habit of despair"—that which numbs people to their pain. Despair has not yet become a habit as long as the loss remains painful, because you continue to hope for reunion: your memory of your loved one has not yet faded."physical connection"The only way to preserve those memories is to do what the people of Oran in "The Plague" avoided: imagine the days of reunion with loved ones – from the things they are doing now to what we will do together when things return to normal. This may be temporarily… more painful, but it is also the only way to truly live amidst the unpredictable changes of the pandemic.

The power of imagination to keep love alive is spectacularly demonstrated through the character of Raymond Rambert, a journalist living in Paris who happens to be investigating sanitation conditions before the outbreak of the epidemic and becomes trapped in quarantine. Rambert likes to spend four hours each morning "thinking about his beloved Paris" and "recalling images of the woman he is separated from." Rambert also dreams of Paris—a kind of reverse anecdote for his lover, who now lives in the bustling city.

“There appeared before his eyes the scene of a naked lover, the old stones and riverbanks, the pigeons at the Palais-Royal, the Gare du Nord metro station, the quiet old streets around the Pantheon, and many other scenes of the city that he never knew he had loved so much.”

Painting: Starry Night over Rhone, Vincent van Gogh

Beyond imagination, humans need the ability to perceive reality clearly. Waiting for peace in the future is not enough; people must still live in the present. According to Camus, the plague is a re-examination of humanity's place in the plan of the universe, beginning with the realization that the philosopher Protagoras was wrong – man is not the measure of the universe.

Camus's absurdism acknowledges that the universe cannot satisfy humanity's ever-present yearning for meaning and love. Plague is also an absurd phenomenon: it is so vast, killing so many people that it leaves little room for respect for their dignity. (Camus's account of mass burials without proper funeral rites is a particularly grim illustration of this reality.) At the same time, the source of the infection, the bacteria, is an enemy too small to be seen and fought. Therefore, at every turn, plague defies humanity's attempts to understand it. What is necessary to live in this reality, according to Camus, is existential humility, an understanding of our true place in the order of things.

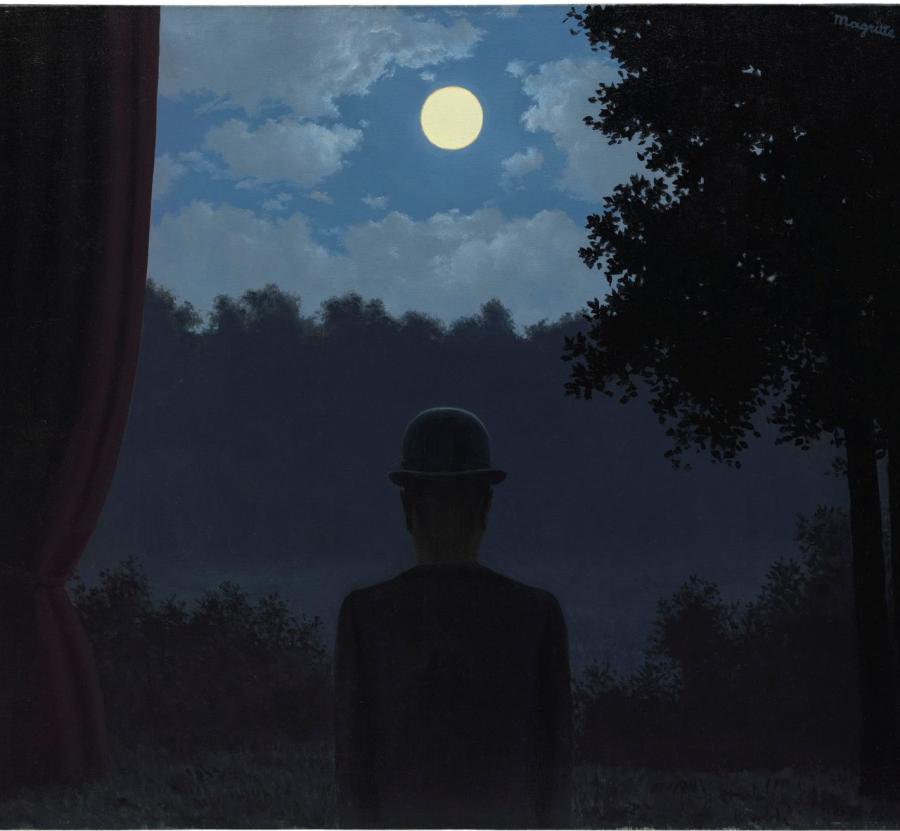

Camus's absurd existentialism also produces a peculiar kind of joy. Near the end of the epidemic, two friends, Tarrou and Rieux, quietly go to the sea at night, thanks to the government passes they possess. As the two men prepare to jump into the water, they are overwhelmed by a "strange happiness" that:Happiness doesn't come from avoiding or denying reality..

What is needed to live in the present moment is existential humility, an understanding of our true place in the order of things. (Painting: Rene Magritte)

Camus's "The Plague," or the story of the Black Death, isn't always a lighthearted soup or a positive, uplifting tale. Darkness and empty despair permeate most pages of "The Plague" and the devastating numbers of the Black Death. But this is precisely what makes Camus's calls for hope and joy so powerful. They aren't born from imagination but rather from the painful reality of suffering, and that suffering propels humanity stronger, making people more human. We can allow ourselves a moment to feel negative emotions, but once that moment is over, we must rise again and continue striving, working together to overcome the difficult times that the pandemic is creating.

VI

VI EN

EN