A remote, desolate place.

Very few tourists come here.

The Tiễn Khấu section of the city wall stretches 20 kilometers across the jagged green mountain peaks. From the valley below, it looks like a layer of cream painted onto each mountaintop.

Located just 100 km north of Beijing, it is quite different from the more well-known sections of the city wall nearby, such as Badaling or the tomb of Tianyu.

There are no souvenir shops or Starbucks, no cable car. No one is waiting to sell you tickets. Nor is there anyone to help you explore more easily: to reach this section of the wall, you have to hike up the mountain for 45 minutes.

The 20km-long Tien Khau section of the city wall stretches like a silk ribbon draped over the mountaintop.

And it was only recently that it was renovated.

Built in the 1500s and early 1600s, this section of the wall was left untouched for centuries.

Approximately 7 kilometers of the city wall are particularly severely damaged. Over time, the ramparts have crumbled into rubble. Some sections of the wall have completely collapsed, leaving once wide passages so narrow that only one person can pass through at a time.

Trees and bushes grew right through the ground, making the walls look more like a jungle than a fortification.

The lack of maintenance on this section of the city wall makes it look picturesque, but it's also dangerous.

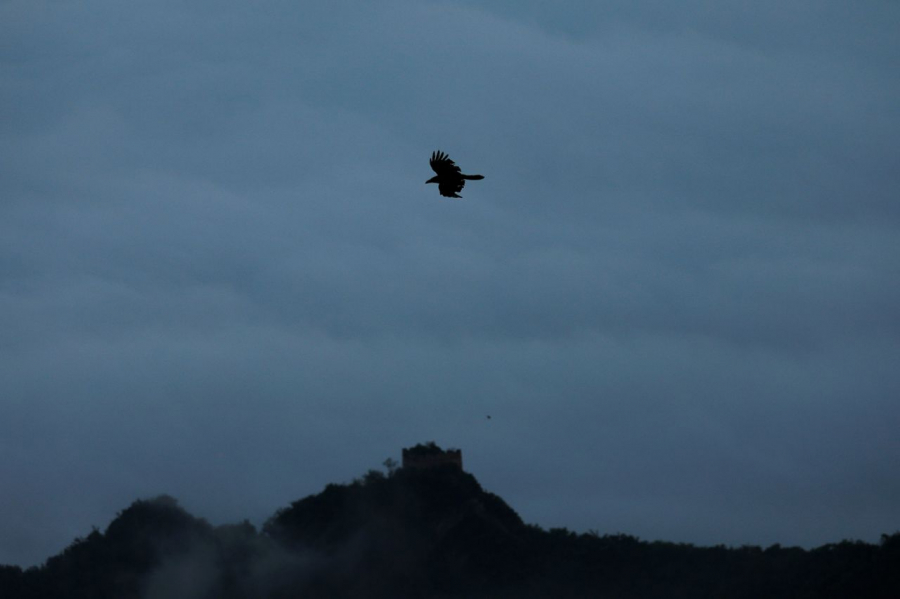

Morning mist in Tien Khau

"Every year, one or two people die climbing this section of the wall," said Ma Yao, manager of the Great Wall Protection Project at the Tencent Philanthropy Foundation, which funded the latest restoration. "Some die from falls. And some from lightning strikes."

To prevent another tragedy from happening – and to preserve the Tien Khau section for future generations – restoration began in 2015. This intensive phase, focusing on a 750-meter section, was completed in 2019.

"Machinery can't be brought here. We have to rely on human labor," Mr. Ma said. "But we should use technology to help workers do their jobs better."

For the 2019 phase of the project, that technology included the use of drones, 3D mapping, and computer algorithms, which could tell engineers whether they needed to cut down that tree or repair that crack – or whether they could leave them as they were and still be safe, as a reminder of the wall that had once been abandoned to nature's encroachment.

"Technology has helped us repair the city wall in the most traditional way possible," Mr. Ma said.

The threat of humans

Winding its way through northern China, from Manchuria to the Gobi Desert and across the Yellow Sea, the Great Wall is vast.

Its history is equally spectacular: it was built over more than 2,000 years, from the 3rd century BC to the 17th century AD, under 16 different dynasties.

The longest and most famous section of the Great Wall belongs to the Ming Dynasty, which built (and rebuilt) it from 1368 to 1644, including the Jiankou section.

Tourists taking photos at Tien Khau

An archaeological survey by the National Administration of Cultural Heritage and the National Survey and Mapping Bureau calculated that the Ming Dynasty city wall stretched 8,851 km – including 6,259 km of wall, 359 km of moat, 2,232 km of natural structures, and 25,000 watchtowers.

Far from being a straight line stretching from A to B, the wall system comprised curved sections, double walls, parallel walls, and protruding headlands.

Today, about a third of the original Ming Dynasty city wall has disappeared. Only about 8% is considered well-preserved. There are many threats: natural erosion from wind and rain; human destruction from construction; and even people stealing bricks to sell. And, of course, there is damage from foot traffic. This happens even at Jiankou, although this section receives far fewer visitors than sections like Badaling.

"On the other side of the mountain are the homes of 20 million people," historian and conservationist William Lindesay said, referring to Beijing. "Therefore, there's the advice 'leave nothing but footprints' - but even footprints can actually damage the wall."

"The Wild Wall"

William Lindesay moved to the foot of Jiankou with his family in 1997 and coined the term "wildwall" to describe the difference between sections of the wall like Jiankou and sections reconstructed for tourists like Badaling. "The wildwall – it's thousands of kilometers long – really makes for the world's greatest open-air museum," he said.

A photographer documents the restoration process of Tien Khau.

His study was cluttered with photographs from his long travels and filled with books about city walls, many of which he had written.

Among the treasures he amassed during his years of studying the ramparts were a 16th-century "stone bomb," hollowed out to hold gunpowder; and a polished crossbow that recreated the type of crossbows archers used to shoot from the ramparts in the early days.

In the more than 20 years since moving here, he has witnessed the gradual decline of Tien Khau.

Initially, he said, he classified this section of the wall as well-preserved. But now it's no longer so. Where the steps were once perfect, they are now worn down by footsteps. The ramparts are crumbling. Climbing the wall has become more dangerous.

"It's impossible to ban people from visiting the Great Wall. That's almost impossible. So, I think the government has no choice but to start rebuilding and stabilizing the wall for safety," Lindesay analyzed.

He paused for a moment. "I love the wilderness wall," he said. "But when the number of visitors reaches a certain point, it's not good. That's when it will be a tragedy."

"Chinese civilization belongs to the world, and everyone has a responsibility to protect the city walls," one sign read. "Take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints," another sign read.

Incorrect restoration

From the top, the restoration project came into view before the wall itself was visible. A mass of scaffolding rose up before me. After several months, the final phase of the project was nearing completion.

"The city wall is the property and heritage of all of us," said Zhao Peng, the chief designer of the restoration project. "Repairing and protecting it is not simply something we are willing to do, but something we want to do – and it is also a responsibility."

But restoring the wall could backfire on protecting it. If a section is renovated too much, it could lose its former character.

Many believe that this is the fate of Badaling, the most well-known section of the city wall. During its major restoration, which began in the 1950s, it was rebuilt with new bricks bonded together with modern cement. Today, many sections are covered in graffiti. Its reconstruction has been ridiculed as "Disneyfication," a contemporary reimagining of the historical monument.

The restoration of Tien Khau was planned to avoid repeating those mistakes.

Mules carried sacks of white ash to the Tien Khau restoration site.

Teams of mules will carry enormous sacks of white ash to the Tien Khau restoration site. Workers will mix this ash into a thick, white liquid. There will be no modern concrete here. They will use trowels to apply mortar to the bricks, carefully placing them into the wall.

The 750-meter section of wall, the centerpiece of this restoration phase, rises above the hill before me. A few trees pierce through the brickwork. It's a far cry from the old forest path of Tiễn Khấu. However, many signs of the wild nature remain.

In another section, one side of the wall had completely collapsed. And at the very end of this section, it ended: it turned into a steep slope down the mountain, so steep that you couldn't survive climbing it without ropes or a rope ladder.

Cheng Yongmao, chief engineer supervising the restoration of Jiankou.

Zhao pointed out the various interventions that had been implemented.

Despite Lindesay's concerns about tourist footprints, the single most significant cause of damage to the Tien Khau section was water erosion.

In the long term, preserving the wall meant altering the rainwater runoff. The restoration team opened drainage holes and other channels to allow the water to flow down.

And in places where water tends to accumulate, they use new bricks that are denser so water can't seep through, and flatter so water can flow away.

New bricks look significantly different from old bricks, a way for future generations to recognize the difference between original and restored.

"Minimal intervention"

"We have a principle—the principle of minimal intervention," Zhao said. "But minimal intervention doesn't mean no intervention at all."

The team working on the Tien Khau project could easily put the bricks back in their original positions.

One of the ways the project minimizes intervention is by using modern technology.

Typically, Zhao explained, the designers would meticulously inspect and survey the city walls, noting any weaknesses. Back in the workshop, they would then find ways to address those shortcomings to preserve the walls for posterity.

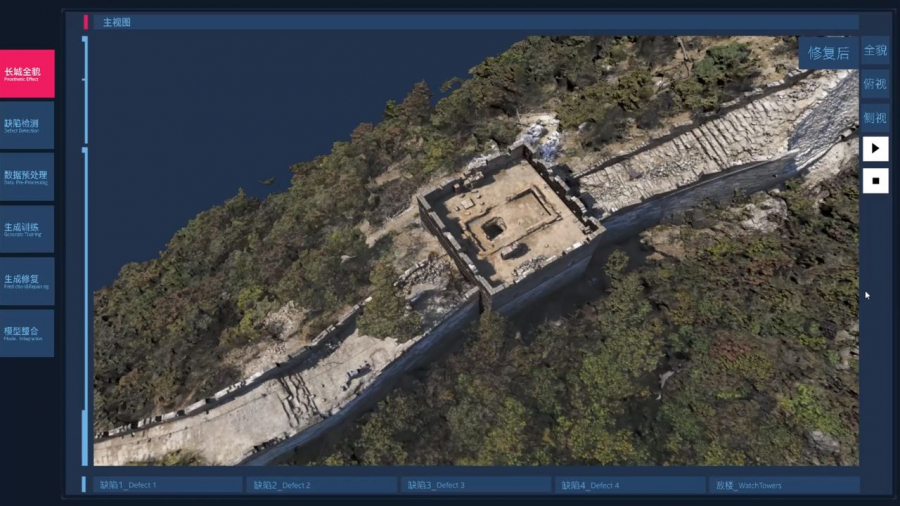

This time, they were aided by a new tool. In Beijing, the School of Archaeology and Museums at Peking University used a drone to fly over the section of the city wall, taking about 800 photos in half a day. Using the images obtained, they would create a 3D model of the wall, detailed down to each brick and crack. To get a complete picture for the restoration work, they repeated this process once more when they were halfway through and again when it was finished.

The use of 3D modeling and algorithms allowed engineers to obtain valuable information about the city walls.

"We've created many 3D models and panoramic images like this at various heritage sites across China," said engineer Shang Jinyu. "But this is the first project where we've been able to use this system as part of a restoration project, in conjunction with other techniques."

This data helps the design team plan repairs to the wall with minimal intervention.

For example, consider a crack in one of the watchtowers. "This crack is very difficult to inspect with the naked eye," Zhao said. "By using drones, taking pictures, and then digitizing the data, we can determine the size of the crack, the degree of tilt in the wall. Then we can decide how stable that section of the wall is."

The data also provides a clear record of each stage of the restoration. "The main purpose of this 3D model is to track the entire repair process," Ma explained.

Every day, workers have to hike up the mountain and perform physically demanding tasks at the restoration site.

Another example is one of the watchtowers, which was overgrown with trees. The tree roots had been cut to prevent the tower from being damaged. To remove the trees, the team needed to remove some of the bricks.

Previously, replacing tiles precisely in the correct position was very difficult. Now, they can replace the original tiles quite accurately in their original positions.

"They repaired the top of that tower, but it still looks like it's been standing there for hundreds of years," Ma said.

Some sections of the Tien Khau city wall have been preserved in their natural state of decay during the restoration process.

Interestingly, the group from Peking University wasn't the only one to come up with this idea.

The computer and technology giant Intel created its own 3D model – their drone took 10,000 photos – and shared its version with the China Foundation for Cultural Heritage Preservation, which is also involved in this restoration project.

Now, the teams are putting their knowledge to the next stage: restoring another section of the city wall.

"That's the Hifengkou section, about 300 km from Jiankou," Ma said. "This section is about 900 meters long. Some parts of it are underwater."

"Similar to the 'Tiễn Khấu' project, we used 3D models. And based on our experience restoring the 'Tiễn Khấu' segment, the team adjusted some parts of their plan based on the results provided by the 3D models."

Under the shadow of one of the ramparts, the workers lay asleep.

Beneath the shadow of one of the ramparts, the workers lay asleep. Their day began with a mountain climb at dawn. While drones and 3D modeling may have aided their design team, they couldn't replace manual labor using chisels and hammers.

Once the restoration is complete, this tranquility may disappear. The "No Visitors" sign will probably disappear as well. Fewer people will be afraid of the "wild wall." More and more tourists will come, not just the bravest.

The wall may be less dilapidated and less dangerous than before. But it remains a striking reminder of the centuries that shaped not only the wall itself, but China as a whole. And its soul, if walls have souls, still whispers of the wilderness.

VI

VI EN

EN