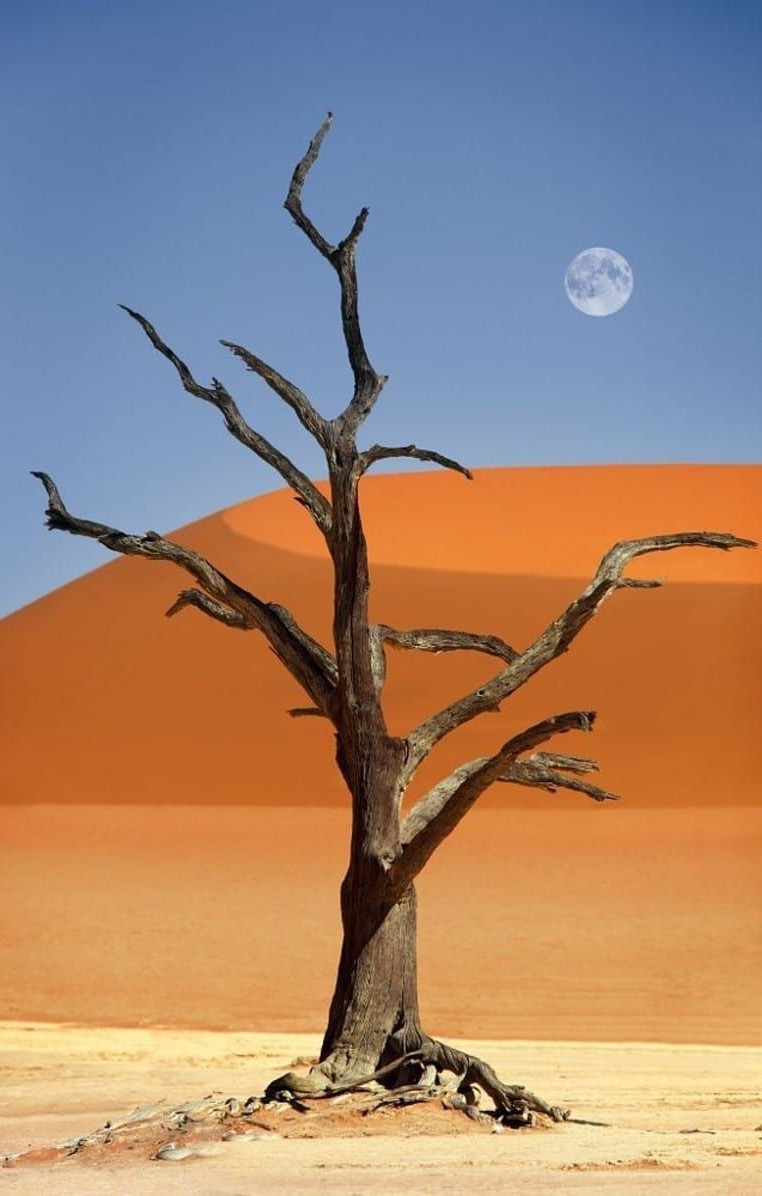

Harsh land

Located along the Atlantic coast southwest of Africa, the Namibian desert is one of the driest places on Earth. Meaning "land of nothingness" in the Nama language, it resembles a Martian landscape with its towering sand dunes, undulating mountain ranges, and rocky plains stretching for 81,000 kilometers.2along this country.

Having existed for at least 55 million years, the Namib Desert is considered one of the oldest deserts in the world (the Sahara Desert is thought to be only about 2-7 million years old). Summer temperatures here often reach 45 degrees Celsius.oTemperatures can drop below freezing at night, making it one of the harshest places on the planet.

But over time, an incredible number of species have adapted and called this arid wonder home – and in the process, created a bizarre geomorphological phenomenon that continues to baffle experts.

The Namib Desert stretches over 2,000 km from southern Angola through Namibia and continues into northern South Africa. From there, the desert breaks into the ocean, a landscape of endless sand dunes extending from the Atlantic coast of Namibia, penetrating more than 160 km inland, to the southern edge of Africa's Great Escarpment.

Organisms adapt to harsh conditions.

The driest parts of the Namib Desert receive only about 2 mm of rainfall per year. For several years, large sections of the desert receive no rain at all. As if out of nowhere, creatures like scimitar-horned antelopes, leaping antelopes, leopards, hyenas, ostriches, and zebras have adapted to survive in the harsh conditions that stretch across the vast desert.

Ostriches raise their body temperature to avoid dehydration, Hartmann's mountain zebras are adept climbers adapted to the rocky terrain of the desert, and scimitar-horned antelopes can survive for weeks without drinking water by eating water-rich foods like roots and tubers.

"Gateway to Hell"

One of the most treacherous and uninhabitable areas in the harsh Namib Desert is the 500-kilometer stretch of towering sand dunes and rusting shipwrecks along the Atlantic coast known as the Skeleton Coast.

Stretching from southern Angola to central Namibia, this region is so named because of the numerous whale carcasses scattered along its shores and nearly 1,000 shipwrecks lying around over the centuries.

The Skeleton Coast is often shrouded in thick fog, formed by the meeting of the cold Benguela Current from the Atlantic Ocean with the warm air in the Namib Desert. This fog creates extremely dangerous conditions for ships needing to navigate, and the indigenous San people call the area "The Place Created by God in His Wrath."

While sailing along the west coast of Africa, the famous Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão passed by the Skull Beach in 1486. Cão and his crew then erected a cross bearing the Portuguese coat of arms, but the turbulent sand dunes of the Namib Desert and harsh climatic conditions quickly pushed it back into the sea – soon after the place became known as the "Gateway to Hell".

majestic sand dunes

Today, tourists come to the Namib Desert to admire the reddish-ochre sand dunes surrounding Sossusvlei, an oasis of salt and clay in the heart of the Namib-Naukluft National Park – Africa's third-largest national park, covering nearly 50,000 square kilometers.2.

Although sand dunes are a common sight throughout the Namib Desert, the area surrounding Sossusvlei has a particularly deep reddish-orange color. This color is actually rust, and is an indicator of oxidation resulting from the high concentration of metals in the sand.

The dunes in the region are also some of the tallest in the world. Many reach heights of over 200 meters, while "Dump No. 7," located north of the vibrant red Sossusvlei, rises to over 400 meters.

One of the many masterpieces of the Namib Desert, and one of its greatest mysteries, is the geomorphological phenomenon known as the "fairy circles." Sometimes called the "fairy rings," these are patches of barren sand encircled by a single species of grass found only in the Namib Desert, and they have puzzled experts for decades.

Desert speckled

These circles are most clearly visible from the air, where one gazes in amazement at the endless matrix of circles stretching across the surface of the desert sand.

These fairy circles are found on both the rocky plains of Namib and on sand dunes, and they maintain their nearly perfect circular shape in both types of terrain.

These circles range in diameter from 1.5 m to 6 m in central Namib, while in northwestern Namibia they are about four times larger and can be as wide as 25 m.

For years, it was believed that fairy circles existed only in Namibia, but in 2014, similar structures were discovered in Western Australia, where environmental scientist Bronwyn Bell was surveying the remote Pilbara region. Confused by the spectacular structure, she contacted Stephan Getzin, a German ecologist and expert on fairy circles, to share her findings. While the circles in Australia closely resembled those in Namibia, the differences in the land formations in the two locations further puzzled the scientists.

Footprints of the gods?

While experts are still baffled trying to find the cause of these "fairy footprints," the indigenous Namibian people have long known about them. The local Himba believe the circles are created by spirits, and that they are the footprints left by their deity, Mukuru.

To understand their origins, many mathematicians have even tried to create models to see if the circles fit into certain patterns.

But Hein Schultz, owner of the Rostock Ritz Desert Lodge located just outside Namib-Naukluft National Park, explains that some locals believe these circles were created by "unidentified flying objects (UFOs) or dancing fairies at night."

Truth

To this day, no theory has been widely accepted regarding the origin of these intriguing crop circles. However, in recent years, scientists from Namibia, Germany, the United States, and elsewhere have been working together to investigate this phenomenon in the hope of gaining a better understanding of it.

At the Gobabeb-Namib Research Institute, a remote research center deep in the desert, entomologist Eugene Marais explains that there are two main theories stemming from the lack of water in the Namib Desert.

Some studies suggest that termites create these circles to collect water and nutrients from the soil. By clearing vegetation from the surface, termites create barren spaces in the soil, allowing rainwater to condense deeper. This theory posits that termites can survive by drinking water from these underground reservoirs throughout the year.

Another theory is "self-organizing vegetation," where the competitive root systems of plants form circular patches that appear as reservoirs, allowing the plants to extract nutrients from the surrounding water.

An unsolved mystery

After years of drought, the fairy grass circles eventually dried up and gradually disappeared. Marais emphasized the wonder of this land and said that, when it rained, suddenly, as if by "miracle," the circles reappeared.

According to Marais, research on fairy circles in Namibia has generally focused only on circles in rocky plains in deserts or in areas with sand dunes. But to truly understand these structures, he believes research must be extended to both types of terrain.

Ultimately, Marais had a hunch that the circular patterns in the desert were the result of a series of factors. But what those factors were remains a mystery to this day.

VI

VI EN

EN