Violence is nothing new in El Salvador. The country endured a brutal civil war that lasted over a decade, beginning in the 1980s. And somehow, this simmering civil war gave rise to a terrifying gang culture where extortion and murder became commonplace.

Following the end of the Salvadoran civil war in 1992, U.S. immigration policies became increasingly stringent. As a result, Salvadoran immigrants with criminal records were deported back to El Salvador, renewing the cycle of gang culture and undermining the foundations of an already fragile and struggling nation.

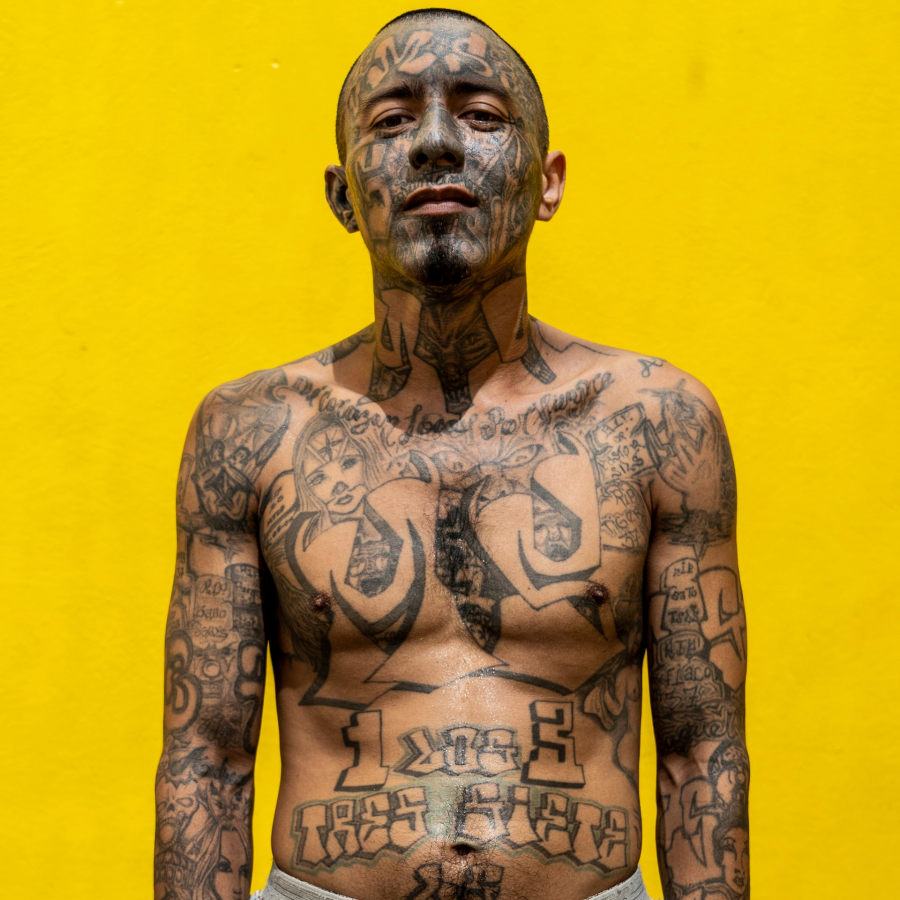

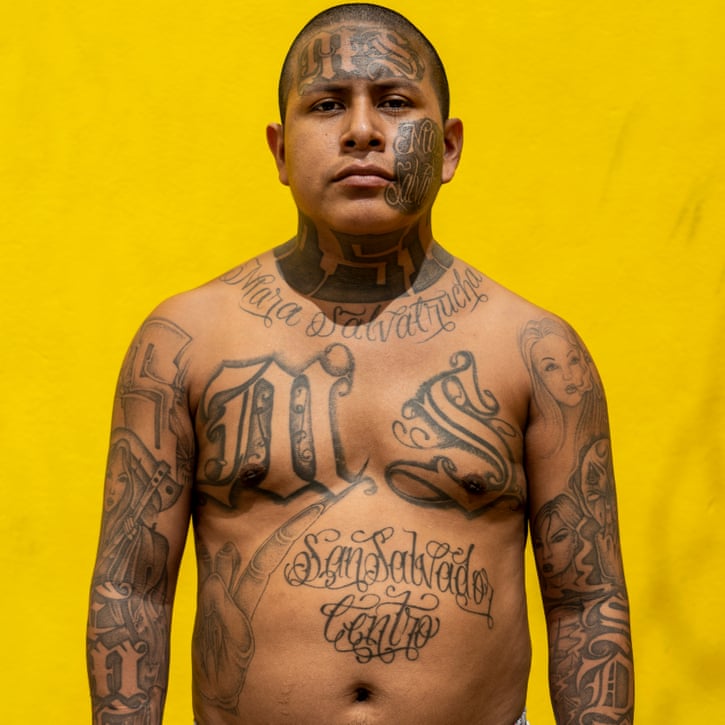

According to InSightCrime statistics, the murder rate in this country skyrocketed in 2015-2016 with over 100 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, almost double that of the second and third highest-ranking countries, Honduras and Venezuela, both with a rate of 59 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. There are at least 60,000 active gang members, mainly from gangs such as Salvatrucha Vampire 13 (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (La 18). This number is higher than the 52,000 Salvadoran state officers, including police, paramilitary, and army forces.

The gangs are composed primarily of Salvadorans who fled to the United States, especially teenagers residing in Los Angeles. While the MS-13 network was comprised of prisoners, La 18 was the city's first multiracial gang. Operating primarily in Central America, La 18 had between 30,000 and 50,000 members in the United States. These criminal gangs continued to grow in number and influence, wielding ever greater control over the country through extortion and coercion.

Today, El Salvador is almost paralyzed. The violent dominance of gangs tears families apart, restricts movement, and paralyzes the government. In El Salvador, disappearance is extremely common. If a body is found, burial is organized as quickly as possible, and the funeral is conducted quietly.

Police officers are always on high alert and wear balaclavas to protect their identities. However, attacks on police officers are still frequent. This breakdown of trust has created a unique socio-political situation, explaining why many Salvadorans desire to migrate to Mexico and the United States. The image of migrants fleeing gang violence in El Salvador and Honduras, then struggling at the southern US border in Tijuana, Mexico, is deeply poignant.

Those living outside El Salvador will find it difficult to understand why social norms are crumbling here. People are sometimes unable to cross a street simply because it's in territory controlled by different gangs. When entering a new neighborhood, visitors often have to flash their lights or roll down their windows to show allegiance to the gang controlling the area.

But the recent election has given the people of El Salvador a glimmer of hope. Nayib Armando Bukele is the new president, young and dynamic. He has created a long-term plan that he claims will eradicate gangs in El Salvador within three to four years. In June, he unveiled a $31 million territorial control plan to increase the police and military presence, aimed at driving out gangs and weakening their control over territories across the country.

Two months later, Salvadoran police had carried out more than 5,000 arrests nationwide, declared a state of emergency in the prison system, attempted to block all communication networks within prisons and with the outside world by shutting down mobile phone signals, and transferred prisoners to more isolated facilities.

He also created a new anti-corruption program called the "Cuscatlan Plan." According to Bukele, economic growth is the solution to poverty and unemployment leading to migration. He succeeded in securing commitments of development funds from both the US and Mexico – one of many steps taken to restore El Salvador's bilateral relationship with the US. However, the fight to eradicate the gangs remains a very long story.

To date, 3,382 people have been reported missing, an increase of more than 200 compared to 2018. The question is, how much longer will the people of El Salvador have to endure this fear and killing?

VI

VI EN

EN