On a cold winter day in 1963, humanity witnessed the passing of a Japanese director. His tombstone bears no name, no age, only the character "mu" (無), meaning nothingness, nothingness.

The director is patient with his own storytelling style.

Yasujiro Oru shared the same birth and death dates, exactly 60 years after his death on December 12, 1903. He hailed from Furukawa, Tokyo, a neighborhood located south of the capital with a network of canals at the mouth of the Sumida River. Later in life, the director often recalled childhood memories through images of bridges or buildings reflected on the water's surface.

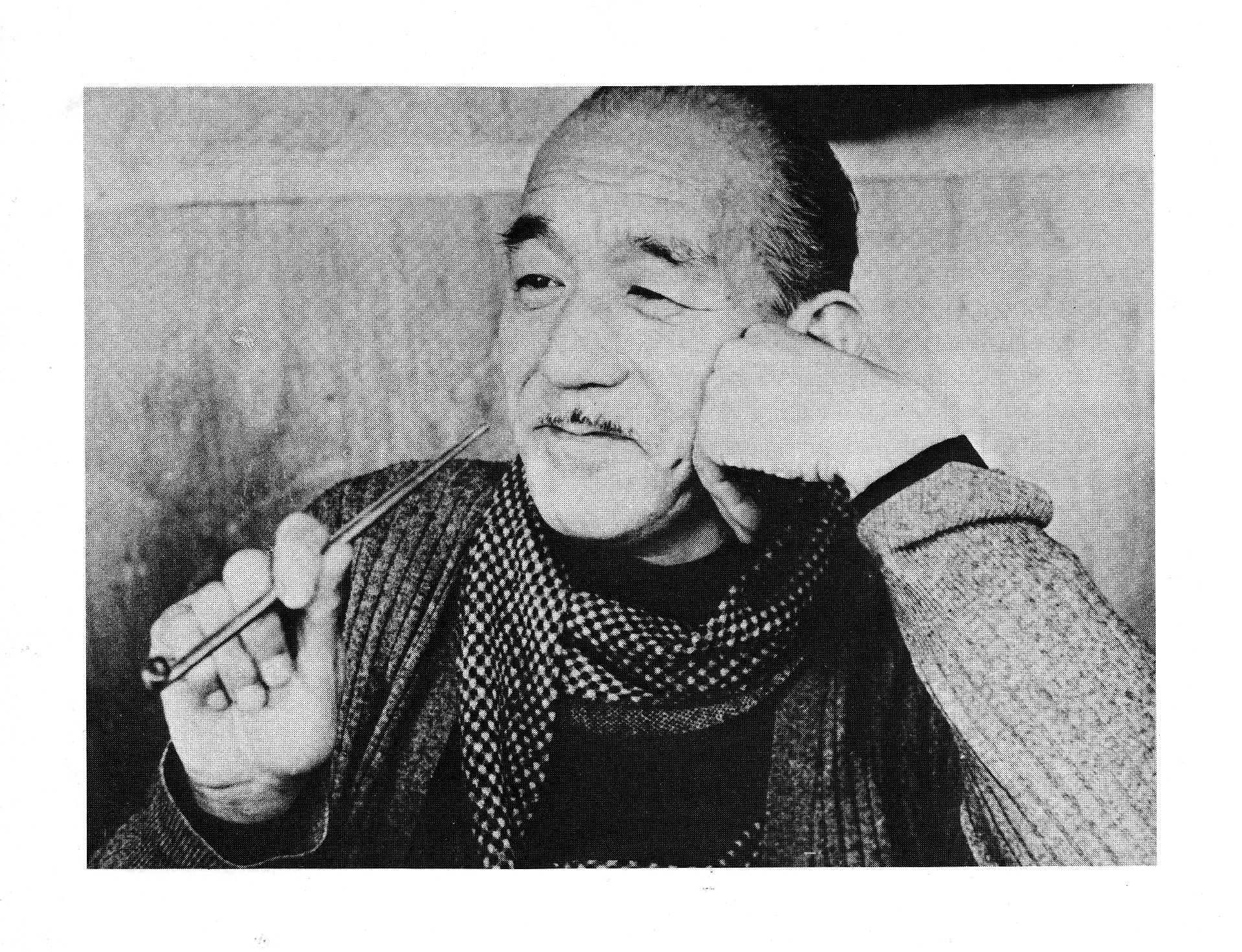

A portrait of the one-of-a-kind director Yasujiro Ozu.

He experienced a turbulent youth, failing the Waseda University entrance exam, struggling to find work in various film studios, and holding back tears as he witnessed his mother's death in 1961. Throughout his later life, he often drowned his sorrows in alcohol and spent sleepless nights writing scripts.

He lived a long and patient life, enduring suffering and sadness as he witnessed the deaths of loved ones, had his work left unfinished in his early years, and chose to remain single until the end of his life.

When entering the harsh world of filmmaking, instead of choosing hot topics or chasing trends, Ozu chose to tell his own everyday stories with a slow, reserved narrative style, and a somewhat detached attitude towards the brutality of the times.

Unique camera angle

Yasujiro Ozu is often called the “most Japanese” of Japan’s great directors. From 1927, his first year with the Shochiku film studio, to 1962, before his death at the age of sixty, when he made his last film, Ozu consistently explored the rhythms and tensions of a nation attempting to reconcile modern and traditional values, particularly in intergenerational relations.

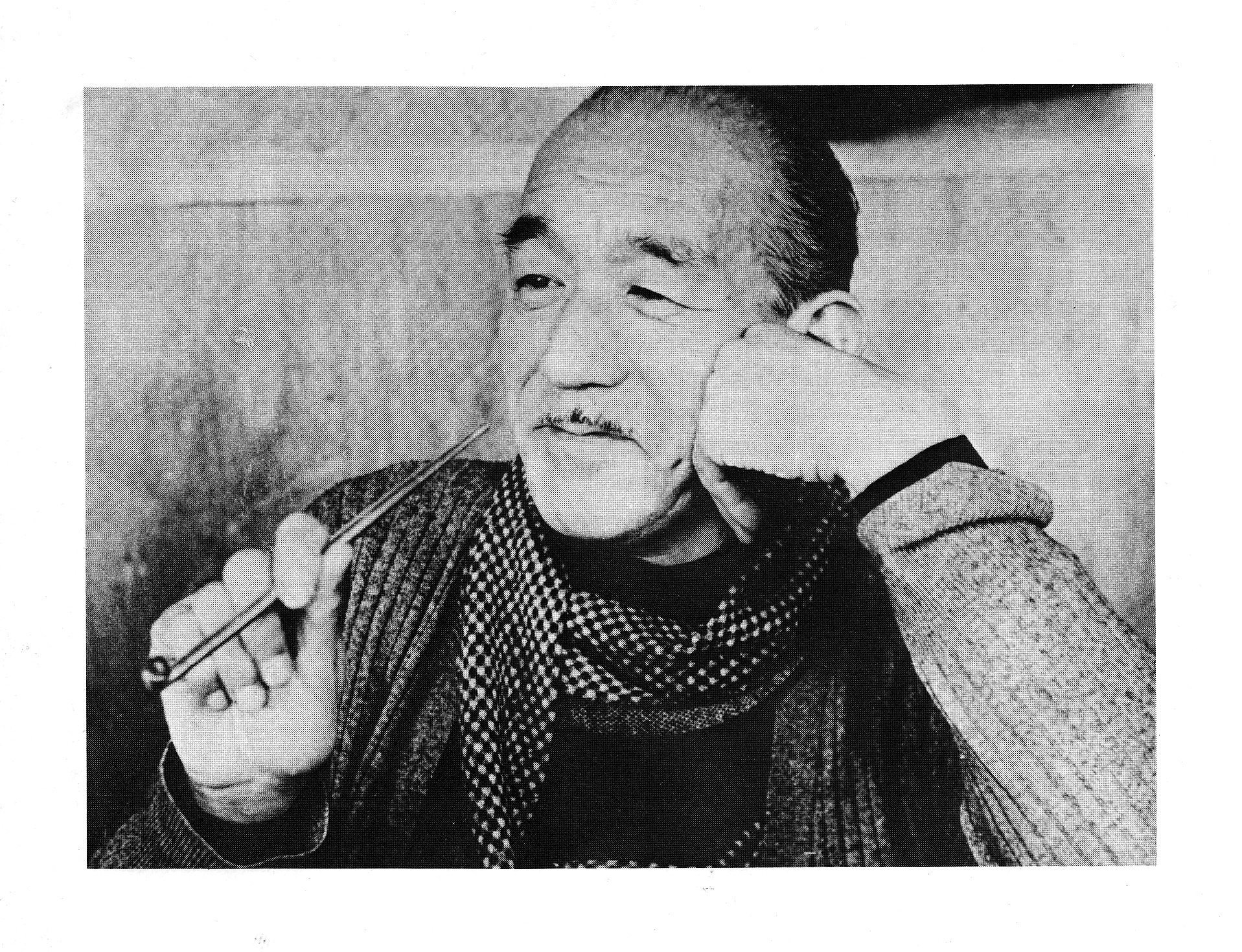

Ozu in his youth.

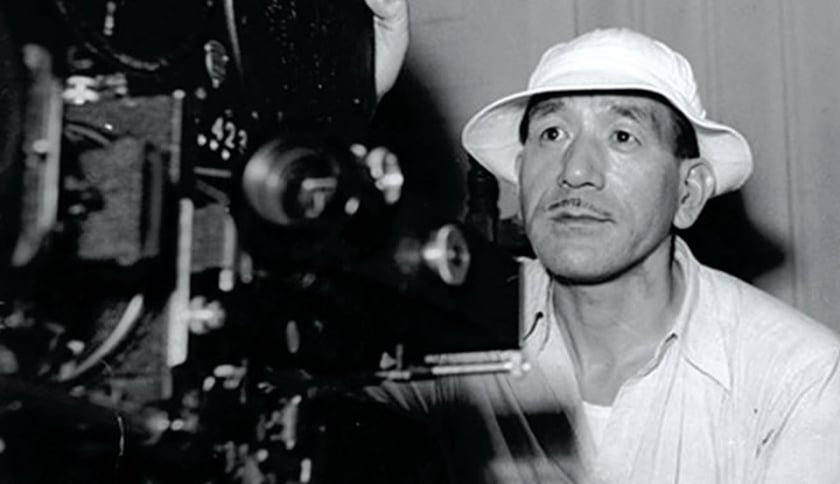

Ozu is perhaps best known for the technical style and innovation in his films, as well as the narrative content. Throughout his films, Yasujiro Ozu chose the "tatami shot" as his primary filming technique. Tatami is the name of a type of mat commonly used in Japan in daily life. He would place the camera on this mat and let it record the scenes, events, and people in the film.

Scenes of a father and son arguing flash across the camera, followed by glimpses of a tree branch, a ceramic vase, and scenes of day and night—all appearing sequentially through a fixed camera angle. Yasujiro Ozu minimized raising and lowering the camera, instead moving it back and forth to capture the scenes exactly as he envisioned them.

The characters in his films seem to possess a full range of emotions—joy, anger, love, and hatred—and the scenery is breathtaking. Ozu's choice of the "tatami shot" as the primary camera angle is as if he himself is stepping back and observing life as it unfolds. Instead of using typical over-the-shoulder shots in dialogue scenes, the camera looks directly at the actors, effectively placing the viewer in the center of the scene. Throughout his career, Ozu used the 50mm lens, often considered the lens that most closely resembles human vision.

Yasujiro Ozu's most famous scene is from the film Late Spring (1949).

He didn't pursue complex filmmaking or technically sophisticated shots, but instead persevered with his own unique storytelling style.

He not only had a distinctive way of framing shots but also impressed everyone with his strict, mechanical work ethic. Many of Yasujiro Ozu's collaborators chose to quit because they couldn't tolerate his harshness. However, when answering the press, he simply shared: "As a director, I'm really just like someone making tofu. Day after day, I do the same simple job over and over again. Then, at some point, everything will naturally become perfect."

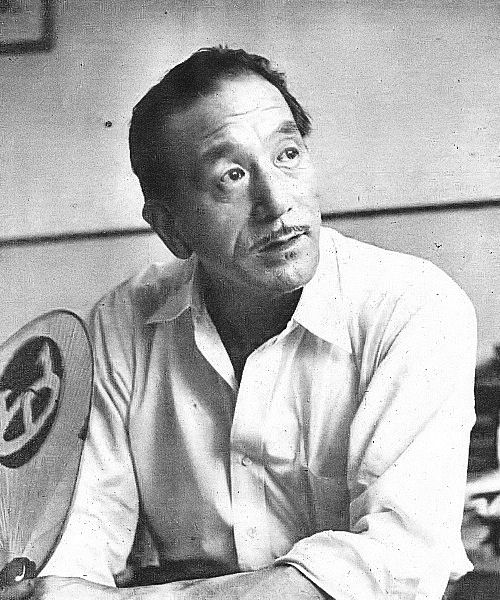

The low-angle shots clearly reveal the characters' expressions.

This is not just his personal trait, but almost a defining spirit of the entire nation of Japan. A country that started from a difficult point but has always been patient and strived for perfection.

Some famous films by Yasujiro Ozu

Although best known for his 1953 masterpiece, *Tokyo Story*, the pinnacle of his portraits of a changing Japanese family, Ozu began his career in the 1930s with more humorous works, though his wit remained intact. He then gradually mastered domestic drama during the war years and later employed humor through body language in numerous films such as "Good Morning," "Late Spring," "First Summer," and "Floating Weeds"...

This director has had quite a few works that have garnered significant acclaim.

However, from the audience's perspective, it seems that his films all feature repetitive actors, details, and storylines. This leads to confusion among many people regarding Ozu's films.

Tokyo Story (1953)

This masterpiece, released in 1953, propelled Ozu's name to global fame and became an immortal work of art. The film even moved a German critic to tears after he accidentally saw *Tokyo Story* at a movie theater while sheltering from the rain.

A scene from the film Tokyo Story (1953) featuring the two main characters. The couple visits Tokyo, goes to a hot spring, and is constantly worried about disturbing their children. They want to get back to their hometown as quickly as possible.

This portrait depicts the subtle details and changes within a Japanese family. Tokyo Story is Yasujiro Ozu's pinnacle achievement. The film, which follows an elderly couple on their journey to visit their grown children in bustling post-war Tokyo, explores the rich and complex world of family life with the director's nuanced and insightful perspective on social issues.

Setsuko Hara portrays the calm and gentle image of the daughter-in-law. She is an actress who has appeared in most of director Ozu's films.

With impressive performances from lead actors Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara, Tokyo Story delves into the easily relatable theme of generational conflict found in Ozu's works, creating one of the greatest masterpieces of cinema.

Late Spring (1949)

Another film that successfully portrays family relationships, just as well as Tokyo Story, is Late Spring. Late Spring tells the story of a family where the father (Chishu Ryu) is preparing to remarry and the daughter (Setsuko Hara) refuses to get married.

This is another famous scene in the film. Completely silent, lasting several minutes, yet it tells the audience a great deal.

The conflicts in the film are gentle and very relatable, as he doesn't try to exploit the harshness of generational gaps or noisy arguments. The scenes always maintain a peaceful and serene quality, true to the spirit of Yasujiro Ozu.

Ochazuke no aji - The Flavor of Rice with Tea (1952)

Ochazuke no aji tells the story of a married couple living in a dull, boring, and suffocating situation where the husband is only focused on work, while the wife stays at home with nothing to do.

One day, Takeo's wife (Michiyo Kogure) lied to her husband, Mokichi (Shin Saburi), saying that their niece had appendicitis and would have to stay overnight in another city. However, the truth was she was out with friends, and this later angered her husband.

The scene shows Takeo's wife sneaking away from her husband to go out.

In the final scene, when the couple reconciles, the husband wants to eat hot rice with tea before his business trip. The wife proactively suggests they cook the dish together, and they enjoy eating it happily.

Although Ozu became known relatively late in the Western world, his characteristic rigorous style—still images, often from the advantageous position of a person sitting low on a tatami mat, patient rhythm, transcendent moments expressed by the unique beauty of small everyday things—has had a profound influence on directors seeking subtlety and poetry in their work.

Hopefully, through these few glimpses, readers can get a glimpse of the portrait of this influential director whose name is widely recognized throughout Japan and beyond, internationally. His films, rich in humanistic values and family themes, will forever live on in the hearts of his audience.

VI

VI EN

EN