A place where the rain rarely stops.

Located in a remote and isolated area, the mountain town of Sangkhlaburi in western Thailand has an indelible connection with"water"The jagged, rocky peaks surrounding the town are enveloped by massive plum-colored clouds, which combine with cool air masses blowing inland from the Andaman Sea across the Myanmar border, causing continuous rain and wind in the area for at least 300 days a year. The rain, which has nourished three rivers for millennia, has created...The Valley of the River Kwai.

The town was submerged.

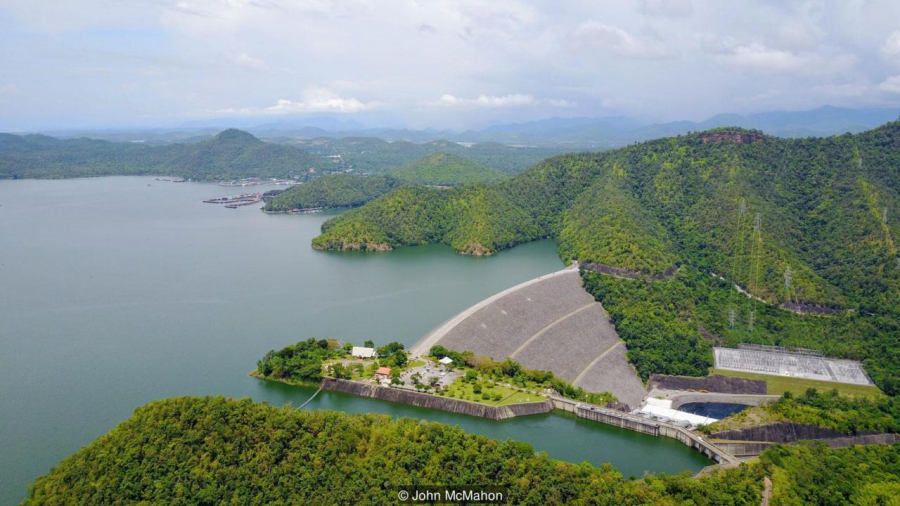

Thailand's first hydroelectric dam was completed in 1982, intended to supplement the country's growing electricity needs and provide a stable water source for irrigation throughout Kanchanaburi province. Upon completion, the dam created the 120,000 square kilometer Khao Laem reservoir, submerging the small valley town of Sangkhlaburi. Residents moved their homes and businesses to higher ground a few kilometers away, originating from Wang Ka – a village previously inhabited by the Mon tribe, who had migrated to Thailand from Myanmar to escape persecution in Burma.

The two towns became one.

After part of the village was submerged, the Sangkhlaburi community split into two groups: those who relocated to higher ground and those who remained in the old village. They face each other across the reservoir into which the Sangkalia River flows. One side is inhabited by Mon, Karen, and Burmese speakers, with narrow streets lined with traditional bamboo and wooden houses. The opposite bank is predominantly Thai. Here, guesthouses and hotels hug the edge of the reservoir, while air-conditioned convenience stores and restaurants sit alongside food stalls and shops.

Some families on either side of the town live in floating houses and make a living from fishing and aquaculture. Like nomadic peoples, they move their homes around the reservoir as the water level changes throughout the year.

A vital artery

Faced with this separation, a hand-built teak wood bridge was begun in 1986 to connect the two communities. With its simple, straight structure and minimal supporting components, it is the longest free-standing wooden bridge in Thailand and the second longest in the world, measuring 850 meters. It serves as a vital link between the two communities, allowing merchants, students, and tourists to travel from one side of the town to the other on foot.

A stateless person

The Mon are one of the first ethnic groups to inhabit the eastern plains of Myanmar (formerly Burma) after migrating from China more than 1,000 years ago. For centuries, many Mon migrated across the border into Thailand to escape the ongoing conflict between the Burmese government and various ethnic groups. Several thousand Mon were forced back into Myanmar by the Thai government in the mid-1990s, but they received permission from the Thai government to live in Sangkhlaburi and other areas across the country, although many are not recognized as Thai citizens.

A model community

"I am Mon and I am also Thai," Luk Luk Wah said as she prepared traditional Mon dishes such as fish curry soup at her shop near the foot of the bridge, in the Thai section of the town. Her mother, a Mon woman, came to the town after her home was submerged by a reservoir, and that is how Luk Wah obtained Thai citizenship. She and her husband, Tong—whom she met after he moved to Sanghlaburi from Bangkok—see the town as a model community where many cultures can coexist without conflict.

"I grew up in the suburbs of Bangkok. For most of my friends and family, leaving that bustling city was unthinkable, but I'm happy here, in a quiet town, learning the Mon way of life," Tong said.

A lighthouse of peace

Even as the residents of Sangkhlaburi, of Mon descent, have integrated into the Thai community, with Mon students attending Thai public schools and their parents frequently exchanging business information, both ethnic groups remain proud to preserve their cultures. Upon returning home from school, Mon children are still taught their language, songs, and stories.

The Mon residency permits in the area have even attracted ethnic minorities from Pakistan seeking a peaceful place to live. This cultural diversity is evident in the Thai-inhabited area, where numerous languages are spoken and food stalls offer everything from lentil dishes and roti to green Thai curry.

A developing tourist destination

In 2013, when heavy rains flooded the Sangkalia River, the bridge's foundations collapsed at the 70-meter span. The massive effort to rebuild the bridge was nationally publicized, enhancing the town's image and increasing its visibility, resulting in a surge in tourist traffic. Today, visitors are drawn to the natural beauty and architectural landmarks of this remote and largely unspoiled region.

Remnants of a vanished settlement.

One of the most popular tourist attractions in the area is Wat Saam Prasob – a Mon temple that was submerged 40 years ago along with the old Sangkhlaburi area. During the dry season from November to February, when the reservoir's water recedes, the temple re-emerges from the lake. During this time, a temporary altar is erected at the entrance for those wishing to worship. Incense is burned, prayers are chanted, and Mon children eagerly sell small fish, eels, and turtles to devotees. They release them back into the lake as an act of merit, a Buddhist practice in which believers perform good deeds to bring them closer to enlightenment.

Two parallel communities exist.

Despite the increasing influx of tourism, Sangkhlaburi retains its unique "dual" character, with wooden bridges connecting the Mon and Thai communities. "The border is just a line, not like a mountain, so it's not difficult to cross," said Pe Win, a Mon man.

VI

VI EN

EN