When Cairo is mentioned, many people immediately think of the Giza Pyramids, the legendary Nile River, or the bustling ancient markets. However, behind that cultural glamour lies a little-known neighborhood – Manshiyat Naser. Unlike the image of a modern city, Manshiyat Naser appears as a completely different world, where waste is an integral part of daily life.

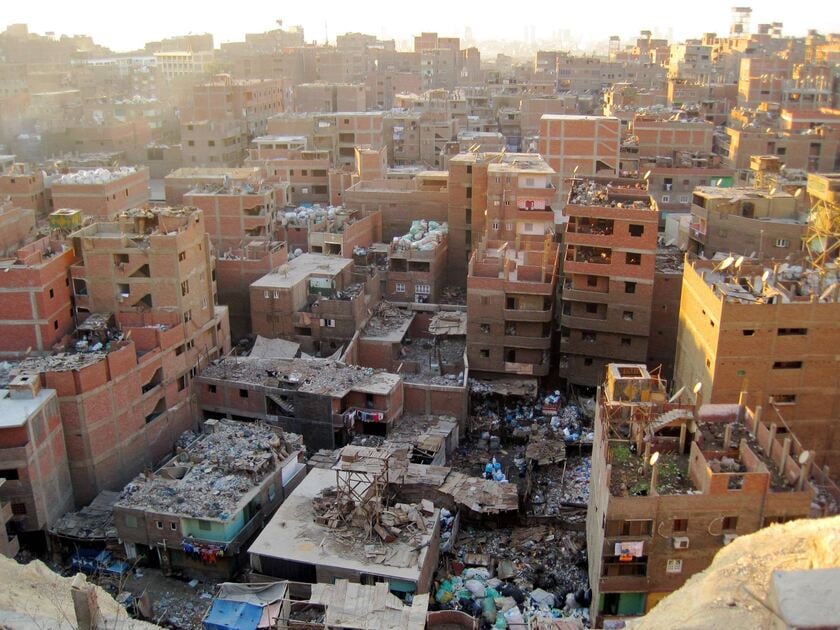

Considered one of Cairo's poorest slums, Manshiyat Naser seems to have been forgotten in urban development plans. Yet, behind its rough exterior lies a whole system of sorting, recycling, and living around waste – a livelihood that has sustained tens of thousands of residents for generations.

Manshiyat Naser, also known as the "Garbage City," is a residential area of the Zabbaleen community specializing in waste disposal located east of Cairo, Egypt.

A neighborhood living amidst garbage.

Manshiyat Naser is located at the foot of Mount Mokattam, in the eastern suburbs of Cairo. With over 60,000 residents, the area is home to a large community of Zabbaleen – Arabic for "garbage pickers." For decades, they have collected garbage from across Cairo, bringing it back to their neighborhood for sorting and recycling.

Contrary to the common perception of garbage collection, the Zabbaleen people carry out this process systematically: waste is sorted at home, separating plastic, metal, paper, fabric, and food scraps. Approximately 80% of the waste is recycled – a rate significantly higher than many major cities worldwide, where this figure typically hovers around 20-25%.

Every day, trucks loaded with garbage are transported from central Cairo to Manshiyat Naser. Here, in unplastered brick houses, garbage is piled high to the ceiling. This seemingly chaotic scene is actually part of the survival ecosystem that the Zabbaleen community has maintained for generations.

Every day, trucks loaded with garbage are transported from central Cairo to Manshiyat Naser.

The heritage and traditions of Zabbaleen

The Zabbaleen community originated from Coptic Christians who migrated from southern Egypt to Cairo in the 1940s. Initially, they made a living by raising pigs and collecting organic waste for animal feed. Later, as the amount of waste in the capital increased rapidly, waste collection and recycling became the main source of livelihood for the entire community.

For the Zabbaleen people, sorting waste is a skill passed down from generation to generation. Children grow up amidst the garbage, learning to identify different materials, how to disassemble parts of old electronic devices, or even how to recycle aluminum cans into useful items. The work is arduous and often stigmatized by society, but it provides them with a sustainable livelihood.

Many households have opened small recycling workshops right in their homes. Some specialize in processing plastics, others in recycling paper, or reusing metals and glass. All of this creates a closed value chain where "waste" becomes a valuable resource.

For the Zabbaleen people, sorting waste is a skill passed down from generation to generation.

Challenges from policy and modernization

Despite playing a crucial role in managing the city's waste, the Zabbaleen people remain marginalized in urban management policies. The Egyptian government has repeatedly attempted to modernize the waste collection system by hiring foreign companies, but the results have not been as expected.

In 2003, the Cairo government contracted with several European waste collection companies. These companies used enclosed trucks, preventing the Zabbaleen people from accessing their waste as they had before. This caused many to lose their livelihoods and significantly reduced recycling rates, as the companies did not implement waste sorting at the source.

Another shock came in 2009, when the government ordered the culling of the entire pig herd – the main source of income for the Zabbaleen community – to prevent an outbreak of swine flu. As a result, thousands lost their livelihoods, while organic waste was no longer processed as effectively as before.

Despite facing numerous challenges, the Zabbaleen people remain resilient in Manshiyat Naser, continuing their recycling work and maintaining the lifestyle that has been passed down through generations.

Despite playing a crucial role in managing the city's waste, the Zabbaleen remain marginalized in urban management policies.

Inside the "Garbage City"

Upon arriving in Manshiyat Naser, visitors may easily be overwhelmed by the sight of crowded streets filled with garbage trucks, plastic bags hanging from balconies, and the distinctive stench of trash permeating the area. However, if you delve deeper, another aspect of the neighborhood will emerge: the diligence, creativity, and strong sense of community of its residents.

A particularly striking feature is the Church of Saint Simon, also known as the "cave," nestled deep within the Mokattam mountains. It serves as a religious center for the Zabbaleen Christian community and is a rare cultural and spiritual symbol amidst a neighborhood often associated with garbage.

In recent years, several NGOs and social projects have stepped in to support the Zabbaleen in improving their living conditions. Schools, health centers, and vocational training programs have gradually been established. However, changing societal perceptions of "scavengers" remains a long way off.

"Perception" – a striking street art piece in Manshiyat Naser, created by Tunisian-French artist eL Seed in 2016. Spanning over 50 houses, the artwork is only complete when viewed from a distance, serving as a challenge to social prejudices against the Zabbaleen community.

Trash is more than just trash.

Manshiyat Naser and the Zabbaleen community offer a different perspective on urbanization, recycling, and sustainability. While many major cities around the world are struggling with waste management, the residents of this "garbage city" are quietly carrying out their daily work, despite lacking formal employment contracts or support systems.

In Manshiyat Naser, trash is not simply something to be thrown away, but a part of life, a source of livelihood, a job, and a testament to human resilience in the face of adversity. And perhaps, within that seemingly worthless pile of waste, lie valuable lessons about fortitude, community, and rebirth.

VI

VI EN

EN